The Insider has launched a series of articles on the long and winding road trodden by Vladimir Yakunin, who went from being Putin's fellow KGB officer and comrade-in-arms to becoming the first boss of Russian Railways, and then an oligarch. Now he has settled in Europe with his family and created an international network to launder money and spread disinformation. In Part 1, we will describe his early period, including ties with the mafia and early corruption scandals, firmly linking him to Vladimir Putin. From this lesser-known part of his biography we learn how Yakunin participated in rare-metal scams, how he took part in «robbery privatization,» and how he issued death threats to deputies for their investigations.

The way of the chekist

Yakunin was born in 1948 in the Vladimir region, but he considers Leningrad, where he moved with his parents when he was a child, to be his real homeland. In 1972, he graduated from the Leningrad Mechanical Institute («Voyenmekh») with a degree in aircraft manufacturing, continued his studies at the Red Banner Institute of the Soviet KGB (now the Foreign Intelligence Academy), and in 1982, as a graduate, headed the foreign nationals department of the Leningrad Physics and Technology Institute of the Academy of Sciences (the deputy director of the Institute at the time was Yury Kovalchuk, another Putin friend and future Yakunin business partner). From 1985 to 1991, Yakunin was an agent for the First Directorate of the KGB in New York under the cover of the Soviet Consul. He returned to the USSR shortly before its collapse in 1991.

According to the biography available to Russian-language readers, Yakunin began working in the private sector in the 1990s, but in his English-language autobiography, The Treacherous Path, intended for Western audiences, Yakunin unexpectedly admits that he left the service only in 1995. The same is true for Putin, who allegedly left the KGB back in 1991 when he joined Sobchak's team, but apparently, he stayed in service beyond that date, in any case, one of The Insider's sources, who worked at City Hall at the time, said that in 1992 Putin went to Moscow to celebrate his promotion with drinks. Franz Sedelmayer, a businessman who knew Putin closely at that time, told The Insider that in his capacity as deputy Mayor he accepted «donations» for the Federal Security Service (the service that succeeded the KGB and was the predecessor of the FSB). Thus, Yakunin successfully combined his publicly known work with his clandestine work for the special services for at least four years.

In his autobiography, Yakunin writes grudgingly about the democrats who demanded that the KGB archives be opened, and says he and his colleagues spent «several days burning KGB archives». At the time, Yakunin had every reason to fear lustration; he would become an «untouchable» figure years later.

Yakunin and Putin's Raw Material Scam

In 1991 there was a catastrophic shortage of groceries in Leningrad/St. Petersburg (the city was renamed on September 6). Despite the ominous WWII blockade associations, ration cards were introduced. The Leningrad Soviet deputies, People's Deputy Marina Salye among them, were among those involved in purchasing food abroad. In the midst of their efforts to save the city from starvation, the deputies accidentally learned that St. Petersburg had been allocated quotas for bartering timber, metals and other goods for food. The Lensovet launched an investigation which found that based on these quotas, ephemeral firms had been indeed exporting raw materials from Russia, but were not delivering any food to the city. Later, all this became widely known thanks to the «Salye Report».

In 1992, the commission headed by Marina Salye concluded that at least $122 million was stolen and misappropriated in «barter» deals; the licenses for the deals were signed by either Deputy Mayor Putin personally or his deputy, Alexander Anikin. The City Council recommended that Mayor Anatoly Sobchak fire Putin on the grounds that he was illegally signing licenses to fly-by-night companies and «pushed» the shipments of raw materials through the customs (see investigative reporter Leonid Dobrovolsky's memoirs «On Putin and sausages» and «The licensing case: selling Russia or saving the city?» with a chronology of events). Putin, however, managed to stay in office despite the scandal.

Dmitry Lenkov, then a member of the St. Petersburg City Council's Foreign Affairs Committee who had been at the forefront of the investigation along with Salye, told The Insider that lawmakers did all they could: Putin's deputy Alexander Anikin was fired, and the «wrongful practice» of such deals came to an end. The Northwest District Inspectorate of the Presidential Administration's Main Control Directorate was also investigating the scandal (see «Sobchak and Putin Called on the Carpet», but «The Results Got Lost in the Archives»).

Lenkov told The Insider that Putin admitted his mistakes both at the March 24, 1992 session of the Petrosoviet, and in a personal conversation just before the session, but added in self-defense: «we are not without sin, but look at what's going on in Moscow.» To give you an idea of what the situation was like in St. Petersburg, Lenkov reminds us that (This refers to deputy Dobrikov who was run over by a car and deputy Kravchenko who was beaten up - they were mentioned in Salye's letter to Vyacheslav Vasyagin, head of the Administrative Department of the President of the Russian Federation. Vasyagin's response is unknown).

Members of the city council kept disappearing» and «it was impossible to prove they were murdered, some were run over by a car, and one of the municipal deputies was beaten up

It was not previously known that Yakunin had been also involved in the scam. But a hint of it can be found in his recently published autobiography:

«One day in 1991 I received a call from a friend of mine, who knew I’d been part of a scientific research institute. He told me that there was a director of a state-owned military factory who needed to dispose of a highly valuable quantity – 900 kilos, a substantial amount – of germanium, a semiconductor material, but that he was worried it could potentially fall into the hands of the bandits who circled those enterprises like vultures».

He goes on to say he then made inquiries about the market price of germanium, helped obtain a certificate of conformity of germanium from a certain Moscow laboratory, and persuaded the factory director to ship the metal in advance of payment. Yakunin is modestly silent on further details of the deal. Could Yakunin, who had been involved in «foreign relations» together with the Kovalchuk brothers at St. Petersburg's Leningrad Physics and Technology Institute, have anything to do with the famous smuggling of germanium and rare metals mentioned in the Salye Report? Former St. Petersburg municipal deputy Andrei Korchagin told The Insider he too had the chance to take part in illegal metal exports in 1991. The offer was received from KGB general Gennadiy Belik (one of the founders of the Foreign Intelligence Service Veterans Association, a good acquaintance of Yakunin's); according to Korchagin, he politely refused. Korchagin says Belik himself was engaged in metal exports, using the resources of the alumina refinery in Pikalyovo. Belik, as Korchagin would later ascertain, was well acquainted with Yakunin. Coincidentally, Yakunin, by Putin's recommendation, would in 1997 became the head of the inspection of the Presidential Administration's Main Control Directorate, which five years earlier had been unable to find criminal intent in Putin's deeds.

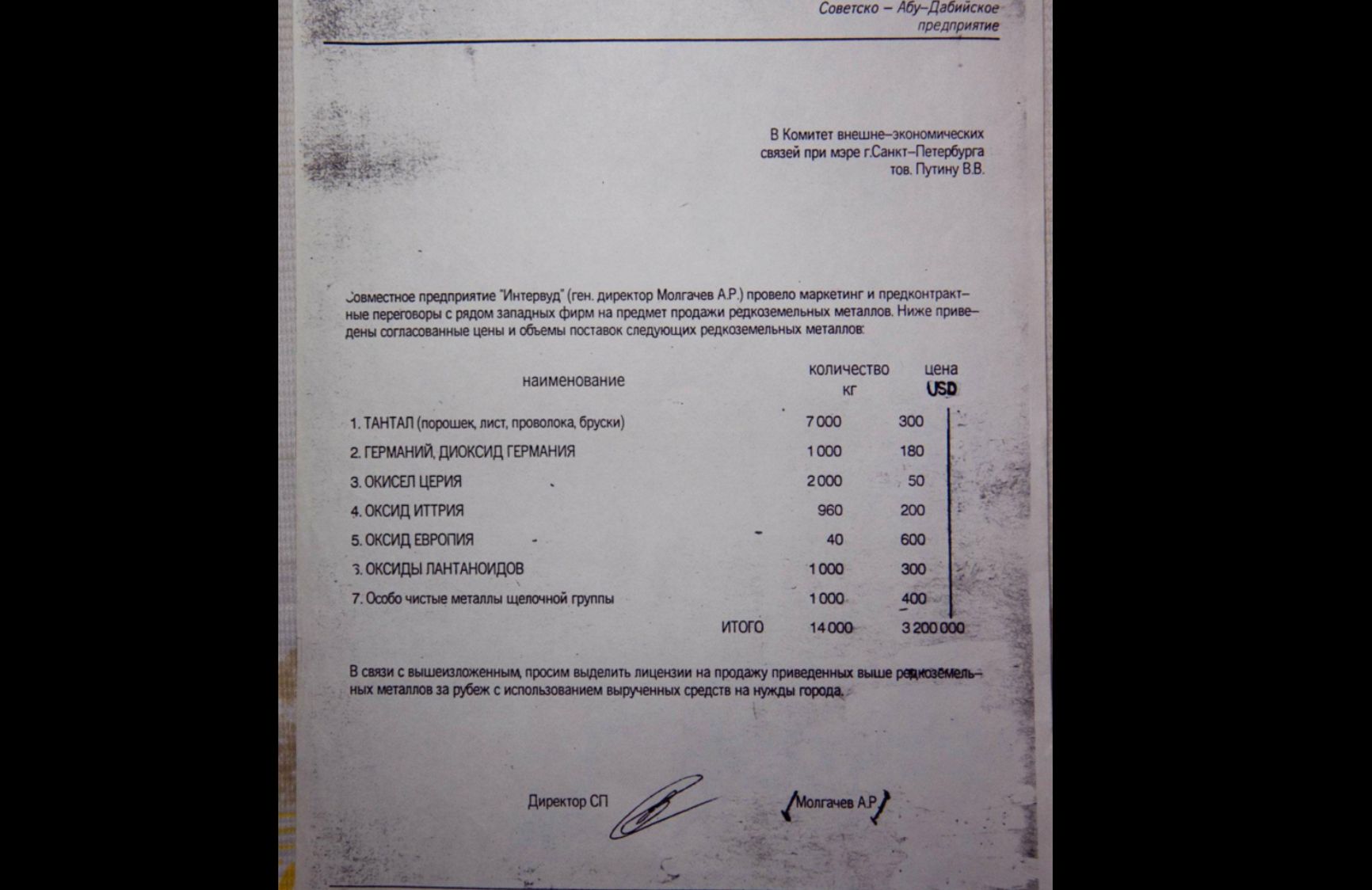

From the documents of the Salye Commission it follows that a total of 14 tons of rare metals were exported by a company called Dzhikop. Moreover, the documents include a request for an export license for one ton of germanium, which was sent by Intervud, but there is no information about the results of the parliamentary review. What kind of company Intervud was and whether it was really related to Belik, Kovalchuk and Yakunin is difficult to ascertain, because the documents of the fly-by-night companies were essentially fictitious, for example, in one instance Intervud is referred to as a Russian-Swedish joint venture, and in another a joint venture between Russia and the UAE, and the signatures of the «executive officers» are inconsistent with one another.

Privatization Manager. Yakunin plays rough in the 90s

In 1996, the State Duma created an interim commission to analyze the results of the 1992-1996 privatization. The Working Group for St. Petersburg and the Leningrad Region in this commission was led by Yuri Shutov, a deputy of the city's Legislative Assembly. The Commission found that Vladimir Yakunin had illegally taken control of St. Petersburg's largest hotel, the Pribaltiyskaya Hotel (officially the hotel had long been managed by Andrey Yakunin's son). Andrei Korchagin, a deputy we already know, supported the commission's findings. He now recalls that Shutov brought similar charges, only in respect of Hotel Astoria, against Vladimir Putin, the Deputy Mayor himself.

In 2000, ahead of a press conference devoted to Shutov's defense - his parliamentary immunity was about to be lifted - Korchagin received an unusual invitation from the former KGB general Gennadiy Belik, who had previously offered him to trade in metals.

Belik invited Korchagin to a meeting with Vladimir Yakunin in his office at the Foreign Intelligence Veterans Association. At this meeting Yakunin, who did not hold any official position at the time, tried to persuade Korchagin to withdraw his support for Shutov. «He said I was a reckless driver,» Korchagin recalled, «and I might get into an accident». So Korchagin once again became convinced KGB officers never retired.

Yakunin said that I was a reckless driver, and I might get into an accident

Korchagin was forced to leave Russia in 2009. Shutov was less fortunate. He was attacked by a group of unidentified assailants, and a few years later, federal judge Alexander Ivanov sentenced him, a former member of the Legislative Assembly, to life in prison for «organizing a criminal group» allegedly involved in contract killings and other crimes. Shutov died in a Russian penal colony in 2013.

In his memoir The Treacherous Path, Yakunin praises investigator Dmitry Shakhanov, who was involved in the Shutov case. Already in his capacity as head of Russian Railways, Yakunin appointed Shakhanov deputy general director of the railway network. Shutov's interests are represented at the ECHR, albeit posthumously, by attorney Karina Moskalenko. According to her, «Shutov's guilt was not proven by the court. Statements against Shutov were made by such legendary figures of «St. Petersburg's underworld» as Roman Tsepov, Ruslan Kolyak, and Vyacheslav Shevchenko. For some reason, more reliable statements, such as those from businessmen who would complain of extortion on the part of the «Shutov gang» are not available.

In 1997, Yakunin was appointed head of the Northwest District Inspectorate of the Presidential Administration's Main Control Department, hence he was supposed to investigate official corruption. «Yakunin did not react in any way when Vasily Kabachinov, a Finance Ministry inspector, asked him to open a criminal case against Putin and other St. Petersburg administration officials on suspicion of embezzling approximately $28 million between 1992 and 2000 allocated for construction in St. Petersburg,» Andrey Zykov, a retired senior investigator at the Petersburg Main Investigation Department, admitted in a conversation with The Insider.

When Criminal Case #144128, «Misappropriation of Construction Subsidies,» was finally opened, Putin had already become President of Russia. The case was quickly closed, Zykov, who investigated it, resigned, Finance Ministry inspector Vasily Kabachinov died in an accident, and the chief police operative in charge of the case, Oleg Kalinichenko, took monastic vows and refused to speak with journalists.

Yakunin helps establish the Ozero cooperative and Bank Rossiya

In his memoir, Yakunin calls the brothers Yury and Mikhail Kovalchuk veterans of «the USSR Buran Shuttle high-tech program». The connection between Yakunin and Kovalchuk can be traced back to the early 1990s, when Yury Kovalchuk served as deputy director of the Ioffe Physical and Technical Institute, the same place where Yakunin had been head of the foreign relations department in the 1980s, before he left for New York as a KGB resident. They then became neighbors: according to the Russian real property registry reviewed by The Insider, Yakunin lived in the same house as Yuri Kovalchuk and in a house at 55 Nalichnaya Street, built by the Baltic Construction Company. Other famous people lived in the same house: Oleg Toni and Alexander Nayvalt (heads of the Baltic Construction Company, the former subsequently becoming a top manager at Russian Railways), Viktor Myachin, the brothers Andrey and Sergey Fursenko. Yakunin, Kovalchuk, Andrei Fursenko and Myachin had as many as two apartments each in this house. As of December 2020, Yuri Kovalchuk's wife kept one apartment there, while Yakunin sold his two apartments in 2009 and 2018.

This closeness was no coincidence. Upon his return to St. Petersburg from New York, Yakunin founded a joint stock company called Temp together with Sergei Fursenko and Yuri Kovalchuk, as well as the International Center for Business Cooperation (ICBC), conceived as «an imitation of the World Trade Center in New York» to attract foreign investment.Only once did the St. Petersburg press of the 1990s mention this megaproject. In September 1993, Temp applied to the then Petersburg authorities (Sobchak, Putin, and Alexei Kudrin) with an urgent request for 50 million rubles from the city budget.

«This is the first time that a joint stock enterprise that was part of the military-industrial complex system has asked for money from the city budget. Temp already received a 20-million-ruble loan from the state (Russia's federal budget), but it failed to use it wisely,» Nevskoe Vremya wrote.

Kovalchuk and Yakunin's joint project, MCDS, is better known. Yakunin got a 49-year free usage of the former building of Political Education House which used to belong to Leningrad Regional Committee of CPSU (Sobchak's decree # 622-p dated June 10, 1994).

«We were trying to do something sustainable, with a moral core, bringing foreign investment and expertise to St Petersburg that would end up being of benefit to the city… Profit was not our main goal,» Yakunin writes in his book.

Nothing is known about any investments Yakunin brought, but he made his profits in the most unsophisticated way possible: by renting the premises he got for free right in front of Smolny to oligarchs Vladimir Potanin and Mikhail Prokhorov. Yakunin says nothing more about the success of this project, though it was supposedly his main activity until 1998.

In 1996, Putin, Kovalchuk, brothers Sergey and Andrey Fursenko, Yakunin, Myachin, and Vladimir Smirnov and Nikolai Shamalov (a Siemens representative in St. Petersburg and later Putin's matchmaker) started the dacha cooperative Ozero in the Priozersky district of the Leningrad region. Yakunin acknowledged the existence of this cooperative in a public interview only in 2013, and in 2015 he spoke warmly of the place. Most likely, the dachas were built without permits and «legalized» in 1996, says former senior St Petersburg's investigator Andrei Zykov. This is indirectly confirmed by Putin himself, recalling in his memoirs First Person that by 1996 he had spent «five years» building the dacha.

Yakunin (center), the Kovalchukis (left) and Putin on Isaakievskaya Square in the early 2000s

In 2011, Andrey Zykov complained to the Environmental Prosecutor's Office about illegal occupation of the lake shoreline by members of the cooperative. The Environmental Prosecutor's Office refused to initiate a case, and Zykov was presented with documents of the legalization of the cooperative «within the existing borders» dating back to 1996.

The Ozero cooperative continues to exist to this day. The Insider saw the list of shareholders for 2011 - the year of the Prosecutor's response to the retired investigator's complaint: Yakunin, Smirnov and Shamalov still retained their stakes, but new shareholders – Sergey Orlov and Igor Ballandovich, members of Yakunin's entourage at Russian Railways, – were also added.

As soon as Putin became President, members of Ozero, who had previously been undistinguished in the public sphere, were appointed to top government and business positions: Andrei Fursenko became the Minister of Education, Yakunin was placed in charge of Russian Railways, the «veteran of high tech» Yuri Kovalchuk became the main beneficiary of Bank Rossiya, established back in 1990, and Nikolai Shamalov became a co-owner of the bank.

As soon as Putin became President, the Ozero members, who had previously gained no distinguished positions in the public sphere, were elevated to high places in the government and business

In the 1990s, Anatoly Sobchak ordered the funds of the Leningrad Regional Committee of the Communist Party to be transferred to Bank Rossiya (of course, for the «development of the city»). Today this bank collects utility bills from the population and controls the National Media Group, whose board of directors is headed by Alina Kabayeva. The accounts of the companies involved in the construction of Putin's famous palace at Cape Idokopas were also opened here, recalls Sergei Kolesnikov, a former partner of Nikolai Shamalov.

Yakunin and the Tambov Organized Crime Group

In his 2018 memoir, Yakunin complains about the criminality and chaos that became commonplace in the 1990s, within the narrative established by Putin himself and his propagandists. For example, «the privatization of the St. Petersburg seaport and the Baltic Shipping Company was accompanied by murders,» Yakunin says with indignation. Of course, Vladimir Putin himself is the savior of Russia who delivered it from criminals.

However, criminals are not strangers to the Ozero cooperative and Bank Rossiya (though Yakunin doesn't mention this). For instance, Vladimir Smirnov, the first director of the Ozero cooperative, was the head of the St. Petersburg Fuel Company, where Vladimir Kumarin (Barsukov), the leader of the Tambov organized crime group, who had been St. Petersburg's «night governor» for years, was the vice president.

For some reason, the first shareholders of Bank Rossiya were the leaders of the Malyshev Organized Crime Group, Gennady Petrov and Sergey Kuzmin. Why were they needed there? Gennady Petrov, in his own words, «was on very good terms with Yury Kovalchuk». This fact became known from his own conversations, wiretapped as part of the Spanish criminal investigation in 2008 (case materials available to The Insider). Apparently, the criminals were effective in recovering debts. Thus, according to the wiretaps, that same year Petrov was even given an important assignment «from Klishin» - to help with the recovery of the loan issued by Bank Rossiya.

Petrov and Kuzmin were previously considered minority shareholders of Bank Rossiya, but in 2018 deputy Vladislav Reznik presented documents to the court in Spain, according to which Petrov was «co-founder of, and owner of a 27% stake in, Bank Rossiya in 1992-2003.» At the «Spanish» trial defense lawyers (Petrov did not show up and is still wanted) called Petrov a «simple billionaire,» a «friend of Putin,» and a «KGB officer» and even presented the court with a written petition stating that Putin and Petrov «had met each other in the KGB,» and Petrov was allegedly helped to settle in Spain by a «fellow officer» in Spanish intelligence.

Interestingly, Yakunin's neighbor and partner Igor Nayvalt, director of the Baltic Construction Company, was also on very good terms with Gennady Petrov. In addition to Bank Rossiya, Petrov turned out to be a «shareholder and co-founder» of BCC. According to the Spanish wiretaps, Nayvalt greeted Petrov on his birthday and Petrov discussed with him tenders involving BCC; Petrov's closest associate, Arkady Burawoy, was employed by BCC. (Click here to read more about ties between Gennady Petrov, the leader of the Tambov-Malyshev Organized Crime Group, and the Russian authorities).

Embezzling port construction money

Before 2005, Vladimir Yakunin was the chairman of the board of the Ust-Luga port on the Baltic Sea. In his memoirs, he describes what an important task it was to construct a new port after the USSR had lost all the ports in the Baltic states. Describing the Ust-Luga port, he even says that instead of counting every penny, he's more inclined to create projects from scratch, although in this case he did not create anything from scratch.

The port had been under construction since 1993, and in 1998 Yakunin was invited as a state inspector to supervise the construction. Yakunin soon became the Chairman of the Board of Directors - allegedly by special permission from the head of the Presidential Administration, Alexander Voloshin; in other words, he combined his government position with business activities. Yakunin's people were in charge of the port and its oil terminals through Investport Holding Establishment, a Liechtenstein company. The port, whose construction was «inspected» by Yakunin, became a major corruption hole.

In May 2013, Boris Nemtsov released a report titled «The Winter Olympics in the Sub-Tropics». It claimed some $25-30 billion had been stolen during the construction of the facilities for the Sochi Olympics. Among the companies most actively involved in embezzling budget funds, Nemtsov named Russian Railways. Yakunin sued Nemtsov and withdrew his claim only after Nemtsov was killed. But the theft was later made official. Valery Izraylit, head of the Ust-Luga port and Yakunin's associate, was arrested in 2016 on suspicion of embezzling 1.5 billion rubles; the investigation is ongoing.

In 2014, Yakunin faced a losing streak: first, he fell under U.S. sanctions, then in 2014, Alexei Navalny told of his luxurious estate near Moscow, with a spacious fur coat storage closet, a guardhouse, a 15 car garage, and other modest patriotic perks of a state-owned company employee. In 2015 Yakunin was removed as head of Russian Railways.

Yakunin's estate in Akulinino with the famous fur coat storage room

After this sad finale Yakunin was almost forgotten in Russia, but in fact, he entered a new phase in his life: he left for Europe where he started launched a storm of activity in order to promote the Kremlin's influence in European countries (and at the same time to continue spending a lot of money), but we will discuss this in the next part of our investigation.

Iva Tsoy contributed to the article

The IJ4EU fund supports cross-border investigative journalism!