Despite sanctions, the World Bank’s June forecast predicts that the Russian economy will grow by 2.9% in 2024, a figure in line with the Bank of Russia’s own expectation. However, these optimistic predictions are no more reliable than horoscopes or card readings. The Insider reviewed GDP forecasts for Russia and the world from the World Bank, IMF, Russian Central Bank, and Russia's Ministry of Economic Development, finding them to be no more accurate — and sometimes less — than simply extrapolating average growth from the trend seen in recent years. This inaccuracy is the result of the fact that the economy of a country is influenced by numerous impossible to model variables — and of course, any framework for foretelling the future must make due with imperfect data while attempting to overcome the subjective biases of forecasters’ themselves.

Content

Inaccuracy: the new normal

Why reading IMF, World Bank, Russian Central Bank, and Ministry of Economic Development forecasts is like reading tea leaves

Methodology issues

Inaccuracy: the new normal

“If recent history is any guide, the experts have some explaining to do about what they told us had to happen but never did.,” lamented U.S. President Ronald Reagan in January 1984, referring to the $30 billion federal budget surplus he had promised four years earlier. Needless to say, the spare cash never materialized, despite a rapid economic recovery. Forty years later, the accuracy of macroeconomic forecasts has not significantly improved. This is problematic, as government policy is often based on these expectations. For instance, due to erroneous forecasts for 2022, Joe Biden’s American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 exacerbated inflation far more than was expected. That same year, investment banks like JPMorgan, Goldman Sachs, and Citigroup expected the S&P 500 stock index to grow — instead, it fell by 19%.

It is understandable when predictions fail due to the intervention of non-economic factors, such as the appearance of coronavirus in 2020, or the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. However, experts also struggle to predict purely economic crises, even under relatively normal times. For example, a study of forecasts from the IMF, World Bank, and independent analysts across 63 countries from for the years 1992 to 2014 found that economists correctly predicted year-on-year production declines in only one out of thirty cases. “Recessions are not rare,” stated IMF macroeconomist Prakash Loungani, “What is rare is a recession that is forecast in advance.” The Financial Times reported that over 27 years, the IMF typically forecasted each October that five economies would face a downturn the following year, while in reality, an average of 26 countries experienced economic contraction.

Another study, this one examining 602 IMF loan programs from 1992 to 2019, revealed that the IMF systematically overestimates high-growth recoveries GDPs while underestimating the recovery indicators for low-income countries. Essentially, forecasters project past indicators onto the future.

Another issue is that political decisions significantly impact the economy, and experts are no more adept at predicting political developments than economic ones. Philip E. Tetlock, who has studied political prediction accuracy for years, analyzed more than 82,000 forecasts from 284 experts and discovered that even the most accurate predictions were only marginally better than random guessing.

The forecasters' psychology also affects their analysis. Economists Rosen Valchev and Luca Gemmi found that experts often undervalue publicly available market data and overvalue new information, especially when it comes from “insiders.” The Russian rating agency ACRA noted that the systematic pessimism or optimism of forecast authors tends to correlate with their industry affiliation. For instance, investment companies' forecasts for the next year's economic growth are generally more optimistic than the consensus forecast. Forecasts from entities with vested interests — like Russia's Ministry of Economic Development or the country’s Ministry of Finance — should be seen as targets rather than actual predictions of performance, according to ACRA.

Philip Tetlock is a professor at the University of Pennsylvania, a political scientist, psychologist, the leader of the long-term research project «Good Judgment,» and co-author of the book «Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction.»

And while economists often argue that even inaccurate expectations are better than nothing, a simple statistical analysis of GDP forecasts made over the past 25 years by reputable expert centers shows that this is not true.

Why reading IMF, World Bank, Russian Central Bank, and Ministry of Economic Development forecasts is like reading tea leaves

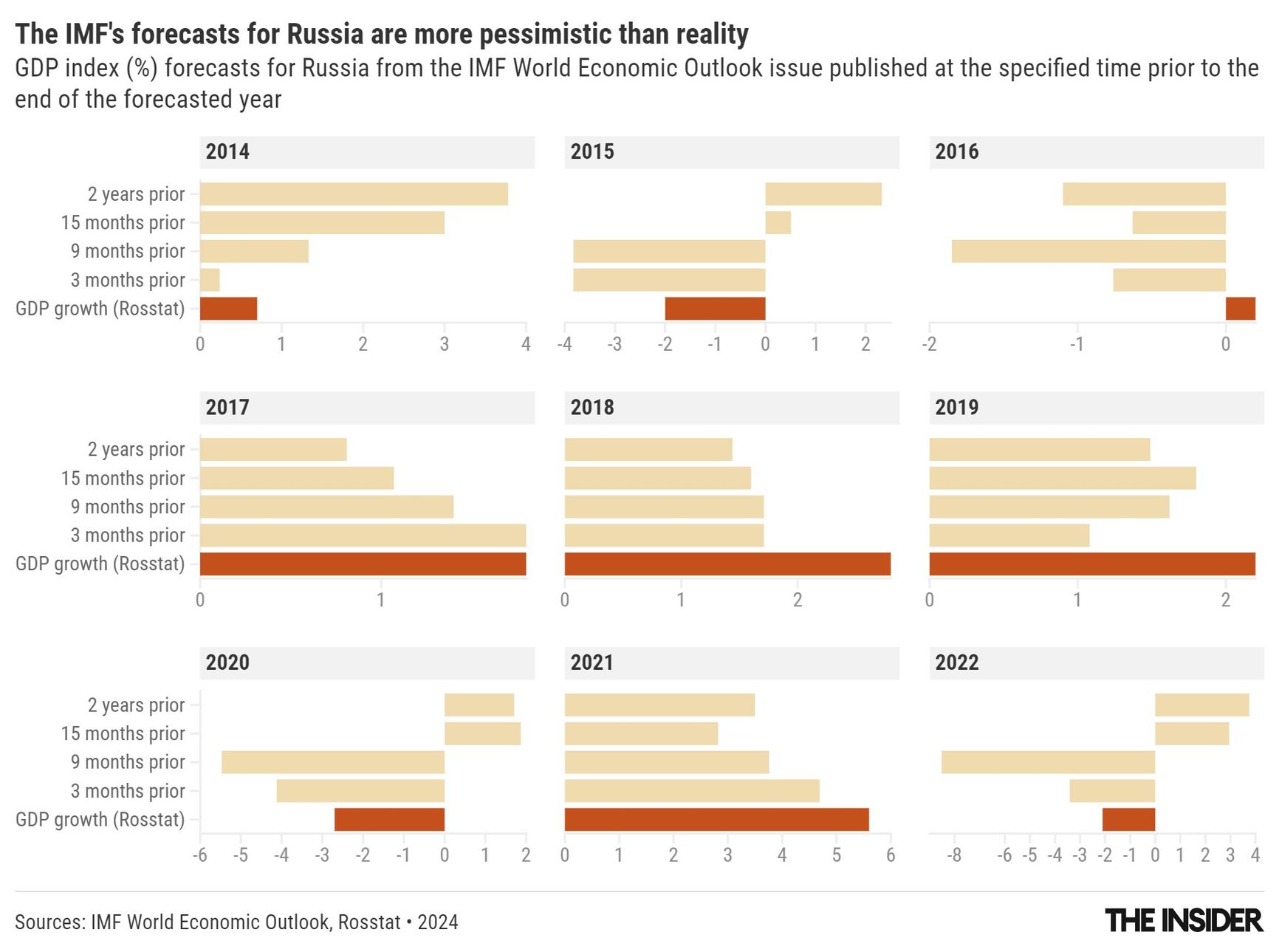

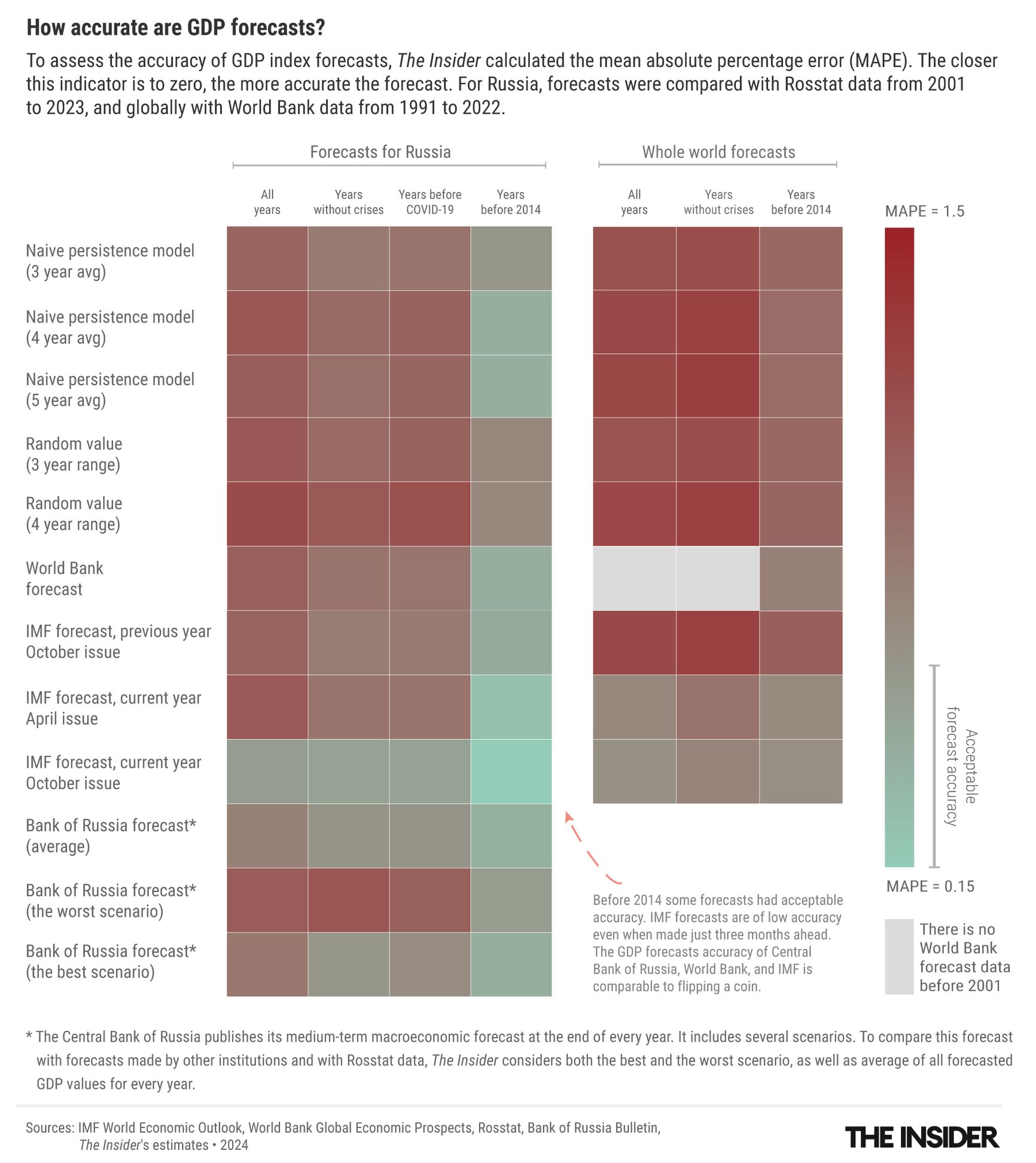

The Insider examined two and a half decades worth of next-year forecasts for global and Russian GDP from the IMF, World Bank (WB), Central Bank of Russia (CBR), and Ministry of Economic Development (MED). The mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) for all these institutions was approximately the same, around 1-1.1 (mean square error - 0.2). Excluding the unpredictable pandemic years, the MAPE slightly decreases to 0.8, but this is still a poor result, as the closer the MAPE to 0, the better is the forecast.

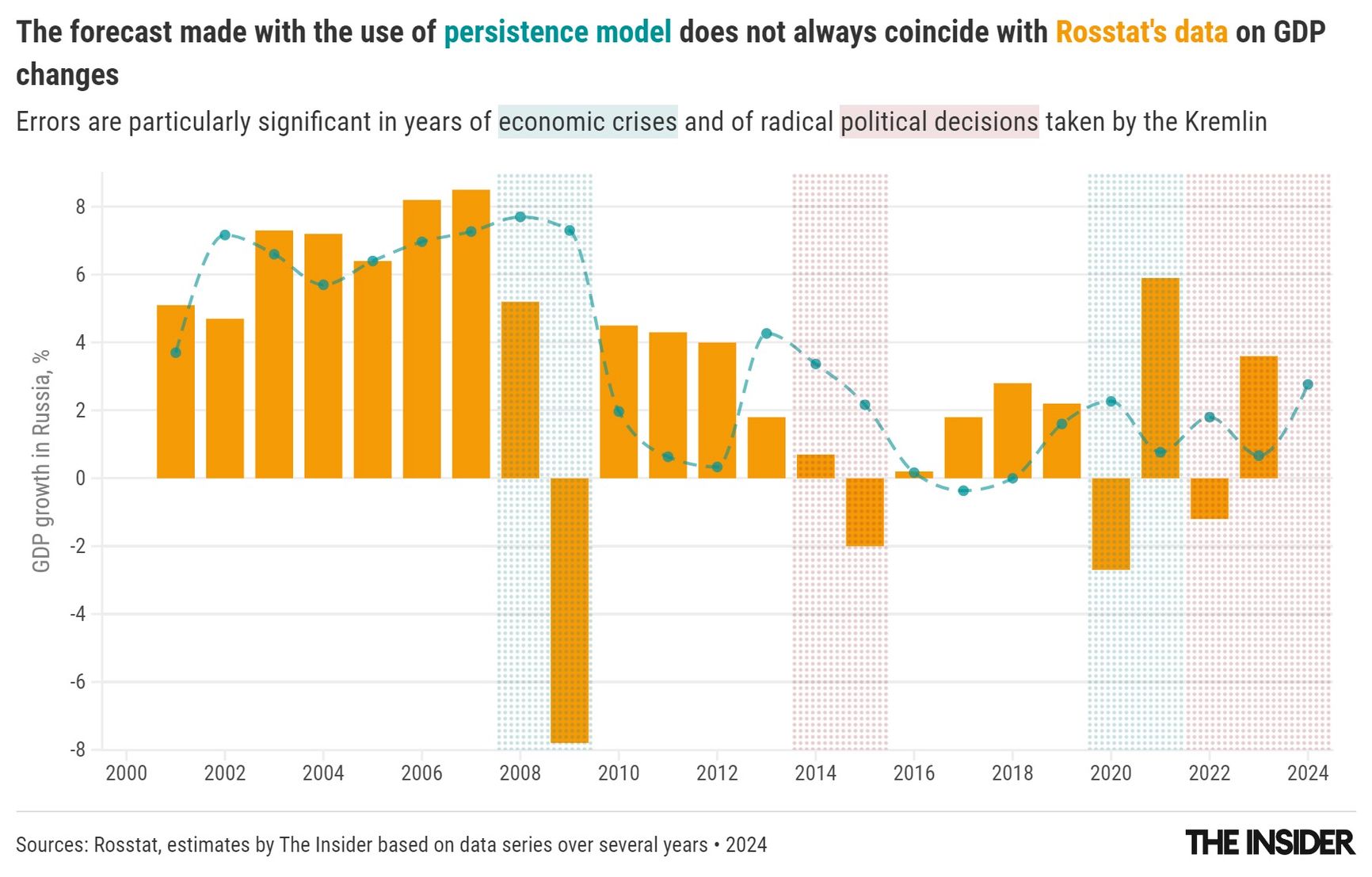

To gauge the accuracy of these forecasts, The Insider compared them with a baseline indicator that involves no expert analysis: taking the average growth over the last three years and assuming it will continue in the next year. This method also yields a MAPE just under 1 for all years and slightly less than 0.8 for pre-pandemic forecasts. Thus, this simplistic projection, which a fifth-grader could calculate, proves to be as inaccurate — or even slightly more accurate — than the predictions from major expert centers armed with complex theories and models.

Philip Tetlock is a professor at the University of Pennsylvania, a political scientist, psychologist, the leader of the long-term research project «Good Judgment,» and co-author of the book «Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction.»

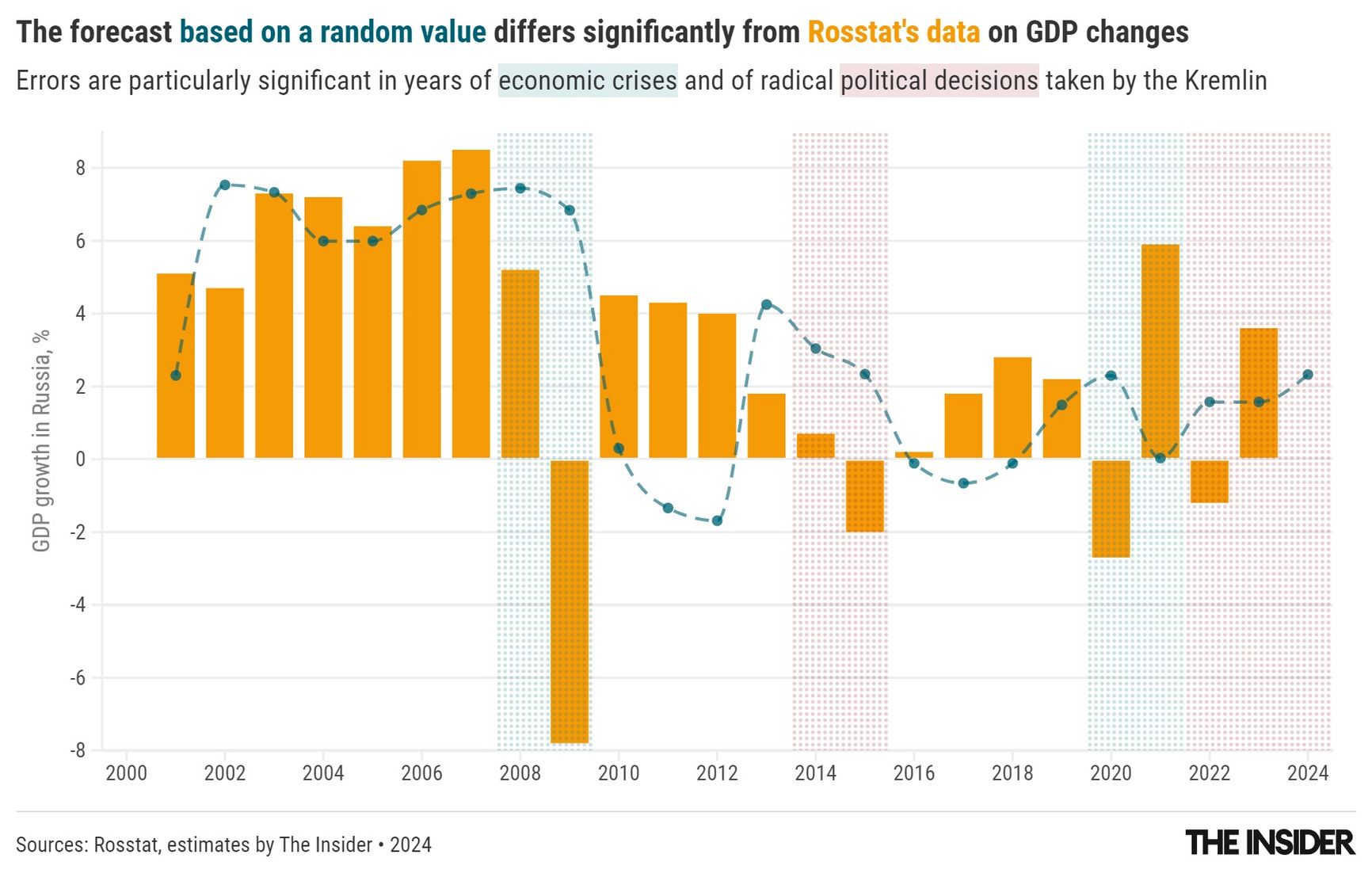

If we avoid projecting past growth into the future and instead make random guesses (a method elegantly termed the Monte Carlo method), the forecast accuracy would be lower, but not by much, with a MAPE of 1.01 for all years and 0.9 for pre-pandemic years. If we also exclude the 2008 crisis from the calculations, the average level of error slightly decreases. However, the naive persistence model that we exercised before remains slightly more accurate than expert predictions, and the “random” forecast only slightly less so.

Philip Tetlock is a professor at the University of Pennsylvania, a political scientist, psychologist, the leader of the long-term research project «Good Judgment,» and co-author of the book «Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction.»

In summary, the “expert” forecast for GDP growth for the coming year is not merely inaccurate; it doesn't qualify as a true forecast. If the model employed by economists has such poor predictive power that the “naive” forecast proves more accurate, it indicates that the model is ineffective, and that there is no justification for using it.

Philip Tetlock is a professor at the University of Pennsylvania, a political scientist, psychologist, the leader of the long-term research project «Good Judgment,» and co-author of the book «Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction.»

Some might argue that experts need to provide at least some forecast for the coming year because governments and investors require this information to plan their policies. However, these stakeholders could just as easily base their expectations on past years' growth, a method that requires no special effort.

In other areas where longer-term prediction is impossible, such predictions are simply not made. For instance, no meteorological service offers weather forecasts beyond a couple of weeks, and it is widely accepted in the scientific community that any meteorologist claiming it will rain in your city precisely two months from today is a charlatan. In economics, as in meteorology, numerous variables are at play, making it impossible to accurately model GDP growth a year in advance, just as it is impossible to predict precipitation a month ahead. So why is it deemed acceptable in the economic community to “guess the result”? Paradoxically, this may be due not to the advanced state of economic theory, but to its underdevelopment. While meteorology has well-studied limits of predictability, economics does not.

Another reason the inaccuracy of GDP and other key macroeconomic forecasts is seldom discussed is that in stable years, the forecast usually really does closely align with reality, satisfying everyone. And in crisis years, economists can typically attribute discrepancies to external, non-economic factors beyond their capacity to anticipate — e.g. the coronavirus pandemic or the war in Ukraine.

Methodology issues

Economists are certainly aware of forecasting’s shortcomings, which is why they often discuss only the probability of certain events, explains Oleg Itskhoki, professor of economics at the University of California, Los Angeles. Take the case of the IMF predicting recession for five countries, when downturns actually occurred in 26. “Analysts were somewhat confident about those five, while the other 21 countries experienced unexpected probabilistic events,” Itskhoki explains. “We can only forecast the probability of such events — say, 10%, assuming recessions occur on average once every ten years. We can also discuss factors that might increase or decrease this probability in the coming year to, say, 5% or 20%.”

Therefore, Itskhoki admits, relying on previous results is often the most sensible approach. “For inflation, the best prediction is to take the average of the previous four quarters. Statistically, the inflation process exhibits some properties of a random walk. If it were purely a random walk, then the best prediction for the future would be the current inflation value. While this doesn't provide an exact forecast, it minimizes the inevitable error.”

Despite these challenges, economists remain hopeful about their ability to predict the future using theoretical models, adapting them to changing realities. For instance, even before Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine, economists noticed based on U.S. statistics that any sharp increase in Department of Defense spending acted as a demand shock. This would lead to a rise in the labor share in total national income, a decrease in unemployment, nominal wages increase,with even higher local rental prices growth rates. Moreover, GDP increased by more than the increase in DOD spending. These observations did not fit into the accepted model, prompting economists to develop a new model that better described this scenario.

Over time, economic models might improve sufficiently to give forecasts slightly better accuracy than random guesses do, but such progress is hindered not only by the complexity of the global order, but also by the fact that these models are handled by people who are susceptible to cognitive biases, such as inertia in thinking and personal interest. Richard Everett, vice president of Chase Manhattan Bank from 1967-1987 responsible for economic research, found that adherents of the ruling political party tend to be optimistic, while their opponents view the future with anxiety.

Moreover, the data used for these calculations are not always reliable. Some data are simply inaccurate, while others become available only after significant delays. As a result, forecasters must often attempt to predict the future without having complete information about the present.

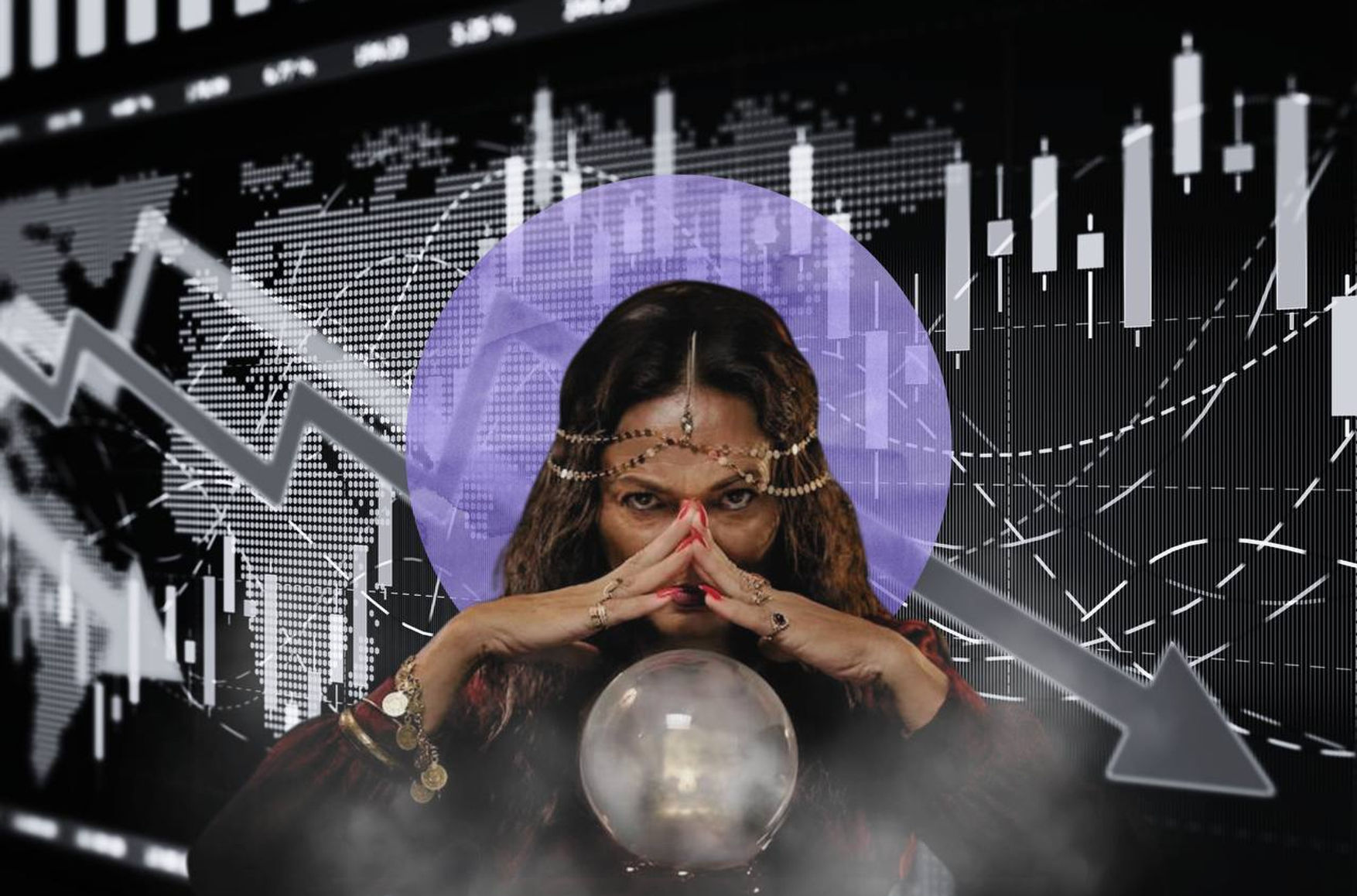

This is especially pertinent for Russia. Both the IMF and the World Bank rely on Rosstat data for their forecasts. However, Russia's short and retrospectively unpredictable history means that estimates can be revised later. Ekaterina Astafieva and Marina Turuntseva, researchers from the Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration, found that adjusted GDP growth estimates are regularly larger than the initial forecasts.

Experts believe these revisions are often unjustified, calling them “an outrageous practice of inflating GDP.” This practice involves both regular underestimation and methodological revisions. For example, in 2015, at the OECD's request, Rosstat included imputed housing rent — the income homeowners would receive if they sold or rented out their properties — in GDP calculations. Given the difficulty of determining the market value of housing in Russia, this indicator is challenging to calculate accurately. And yet it allowed for a nominal GDP increase of several percent. Among Rosstat's recent “improvements” is a new methodology for calculating the creative economy, which is also expected to make GDP growth appear more impressive than it is in reality.

Philip Tetlock is a professor at the University of Pennsylvania, a political scientist, psychologist, the leader of the long-term research project «Good Judgment,» and co-author of the book «Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction.»