While Soviet and Hollywood narratives pay little attention to how Germans resisted Nazism, in reality, Hitler had millions of opponents both within and outside Germany, and anti-fascist Germans who emigrated to Stockholm and Zürich formed the core of the post-war political elite (take Willy Brandt, for one). Here are some of the milestones in the almost-forgotten history of the German Resistance.

Content

Saving Jews in furniture boxes and holding mini strikes

German «zoot suiters» vs. Hitler Youth: fights and leaflets

Unrest among the elites: plots and attempts on Hitler's life

Quiet clerical resistance: crowded services and sermons

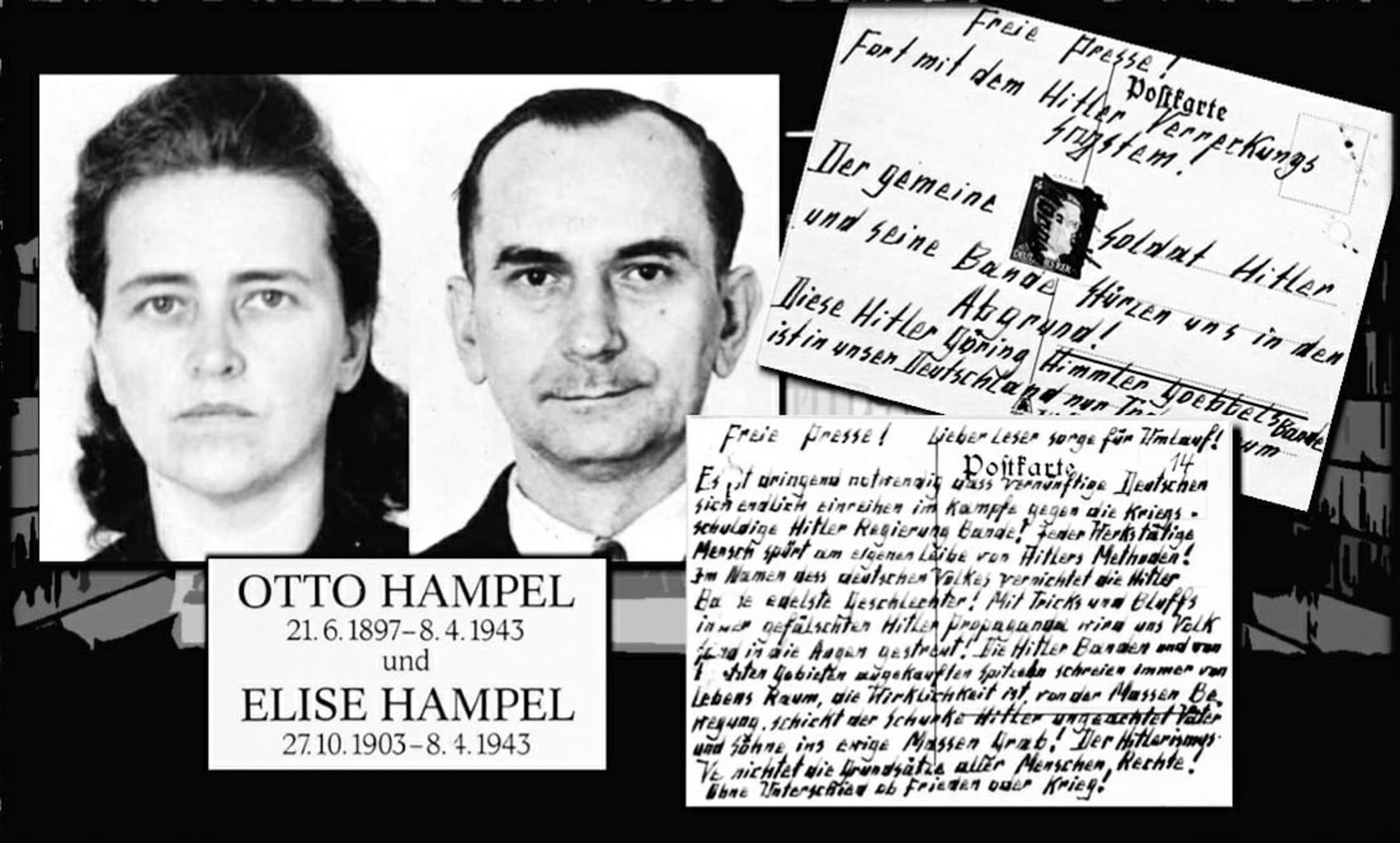

On April 8, 1943, a few months after the Germans took a beating at Stalingrad but long before it became clear that Germany had lost the war (on the same day the Soviet command reported to Stalin that a major German offensive is impossible but that the enemy can reach the line Liski – Voronezh – Yelets), Gestapo beheaded two factory workers in Plötzensee prison in Berlin.

Otto and Elise Hampel were a working-class couple. After Elise's brother died at the front in 1940, they decided to fight the regime in their own way, by writing postcards calling for the overthrow of Hitler and refusing to cooperate with the Nazis, join the military, or donate money to the regime. In two years they signed over 200 postcards, most of which were immediately delivered to the Gestapo.

Elise and Otto Hampel and their anti-Hitler postcards

The story of the Hampels was fictionalized in Jeder stirbt für sich allein (Every Man Dies Alone), a Hans Fallada novel written in 1947. It was the first novel of its kind from an author who had not emigrated. The couple of reticent workers with their postcards was followed by a pleiad of other Resistance fighters: an underground youth cell at a factory, a communist with a portable printing press in his suitcase, a retired judge hiding a Jewish neighbor, and many more.

It is important to appreciate the scale of the Resistance movement within Nazi Germany while acknowledging its heterogeneity and the lack of centralized command. In assessing the scope of the German Resistance, we can only rely on circumstantial signs, such as the numbers of those arrested and executed, like the Hampels.

During World War II, Hitler's Germany executed between 15,000 and 77,000 opponents of the regime. The Gestapo arrested and imprisoned up to 800,000 for political reasons. Almost everyone who ended up in its cellars was beaten and tortured.

During WWII, Hitler's Germany executed between 15,000 and 77,000 opponents of the regime

In structuring the Resistance within Nazi Germany, we can distinguish the following categories:

· Unorganized resistance, which included independent activists (like the Hampels), those who harbored and rescued Jews, and participants in sporadic street protests.

· Youth groups, most prominently the White Rose and the Edelweiss Pirates, as well as the Swing-Jugend (“swing youth).

· Resistance in the German army and foreign ministry, including among commanders.

· Opposition-minded priests, both Protestant and Catholic.

Saving Jews in furniture boxes and holding mini strikes

Resistance is a rather vague term that today's historians use when referring to all kinds of people in Hitler's Germany, from the “Righteous Among the Nations” to those who skived off factory shifts (there is also the term “everyday resistance”, meaning small, routine acts of protest).

Such protesters were mostly ordinary Germans, whose discontent with the government and the war took “passive” forms, such as deliberate absenteeism from work, faking illness, spreading rumors, listening to “enemy” radio voices, black-market trading, and evading near-mandatory Nazi donations (something the Hampels called for in their postcards particularly often).

However, this day-to-day protest was not always quiet. Its more active forms included warning people of impending arrest, hiding them or helping them escape, and deliberately turning a blind eye to and condoning “illicit activities”. Occasionally there were short strikes, and if the demands were purely economic, the instigators were not even severely punished.

Another form of individual resistance (one with much higher risks for all involved) was helping persecuted Jews.

Although the deportation of German and Austrian Jews to the death camps in occupied Poland went unnoticed by the vast majority of Germans, a minority continued to try to help the Jews, despite grave risks to themselves and their families. This was most pronounced in Berlin, where, according to various estimates, up to two thousand Jews successfully hid until the very end of the war (among those hiding them were both public officials and army officers).

Countess Maria von Maltzan saved some 60 Jews through the Aktion Schwedenmöbel (“Swedish Furniture Campaign”): the persecuted were hidden in furniture crates, which Swedish citizens were allowed to send home, and transported out of the country. Protestant pastor Heinrich Grüber smuggled Jews into the Netherlands. And Elisabeth von Thadden, the principal of a private school for girls, continued to enroll Jewish girls until May 1941 – despite all official decrees. When this came to light, the school was nationalized and Thadden was fired (and executed three years later).

Countess Maria von Maltzan

German «zoot suiters» vs. Hitler Youth: fights and leaflets

Importantly, Nazism relied on German youth, especially from the middle class, from the onset and also had the strongest influence on them. Researchers show that German universities were “Nazi strongholds” even before Hitler formally came to power.

Hitler's official youth organizations, primarily the Hitler Youth, were very successful in recruiting children and adolescents. They only faced some difficulties in the rural Catholic regions of the south. But after 1938 and especially after the outbreak of World War II, this began to change: the younger generations regarded the Nazis in power with increasing skepticism.

In truth, their “opposition” to the regime was mostly passive, limited to dropping out of mainstream society and the official ideology and withdrawing into themselves, their private lives, and their entertainment. Even the term Swing-Jugend emerged as a kind of antithesis to the Hitlerjugend, which was especially popular in Hamburg.

German youth were “dropping out” of society and official ideology, withdrawing into themselves, their lives, and their entertainment

They were not dissimilar to their American “zoot suiter” counterparts: groups of apolitical youth getting together to listen to jazz and swing and dance. Their language was littered with Anglicisms, and their outfits, contrary to the Prussian military style, were motley and baggy, with girls often sporting defiantly bright makeup. They hardly ever talked about politics directly, only occasionally greeting each other by shouting in jest: “Swing Heil!” The Nazis looked the other way at first but later, during World War II, began to persecute the Swing-Jugend as opponents of the regime.

However, there were also far more serious youth groups, most notably the Edelweiss Pirates, the Leipzig Bandits, and the White Rose.

The so-called Edelweisspiraten (Edelweiss Pirates) were a network of working-class youth groups scattered across multiple cities, holding underground meetings, and engaging in street fights with the Hitler Youth. A group more radical than the “pirates” were the so-called Leipzig Bandits (Leipzig Meuten), a pro-Communist, anti-Nazi association. By the Gestapo’s estimates, the “bandits” numbered about 1,500 people on the eve of World War II.

The Edelweiss Pirates

Perhaps the best known was the White Rose (Weiße Rose), a non-violent intellectual resistance group led by five students and a professor from the University of Munich: Willi Graf, Kurt Huber, Christoph Probst, Alexander Schmorell, Hans Scholl, and Sophie Scholl. Alexander Schmorell was, incidentally, a Russian German from Orenburg and was later canonized by the Orthodox Church.

The group conducted an anonymous leaflet and graffiti campaign calling for active opposition to the Nazi regime. Their activities began in Munich on June 27, 1942, and ended with the arrest of the core group by the Gestapo on February 18, 1943. Three times in February 1943 (notably, against the background of a recent defeat at Stalingrad), they wrote slogans like this on the walls of Munich University and across the city: “Down with Hitler!” and “Freedom!”

However, failure soon awaited the White Rose. They printed leaflets, and when one of the members, Sophie Scholl, took them to the university and started throwing them around from the balcony, a guard saw it and called the Gestapo.

Sophie Scholl, as well as other members and supporters of the group who had continued to distribute the pamphlets, were put on trial in the Nazi People's Court (Volksgerichtshof); many of them were sentenced to death.

In July 1943, Allied planes scattered the sixth and last White Rose leaflet over Germany with the headline “The Manifesto of the Students of Munich”. In total, the White Rose produced six leaflets, which were copied and distributed in a total circulation of about 15,000 copies. They denounced the crimes and oppression perpetrated by the Nazi regime and called for resistance. In their second leaflet, they openly condemned the persecution and mass murder of Jews. At the time of their arrest, the members of the White Rose were just about to establish contacts with other German resistance groups.

Unrest among the elites: plots and attempts on Hitler's life

There was, of course, no “divide” in the Nazi elites, as political scientists put it now. But there were dissatisfied individuals, both in the military and in the civilian ranks (primarily in the Foreign Ministry).

Several times this discontent resulted in the emergence of conspiracies that planned both coups d'état (beginning with the occupation of Czechoslovakia in 1938) and assassination attempts on Hitler (in 1943 and 1944, respectively).

Relations between Hitler and his military commanders soured for the first time after the dismissal of the Minister of War, Field Marshal General Werner von Blomberg, and the Commander-in-Chief of the Land Forces, Colonel General Werner von Fritsch, following the Blomberg-Fritch crisis, when Hitler finally secured carte blanche to attack new countries.

The failed plots of 1938-1939 revealed both the strength and weaknesses of the officer corps as potential leaders of the Resistance movement. Their strength lay in loyalty and solidarity. As American historian and Columbia University professor Istvan Deak noted, “Officers, especially of the highest ranks, had been discussing, some as early as 1934 ... the possibility of deposing or even assassinating Hitler”.

Officers discussed the possibility of deposing or even assassinating Hitler

Remarkably, this sprawling, poorly structured conspiracy went uncovered for over two years. A possible explanation is that Himmler at the time was still preoccupied with the Nazis’ more obvious enemies – the Social Democrats and the Communists (and, of course, the Jews) – and was oblivious about the real stronghold of opposition within the state apparatus. Another factor was the success of Wilhelm Canaris (head of the German military intelligence and counterintelligence, who, incidentally, also saved some 500 Jews during the war) in protecting the conspirators.

After that, the conspiratorial groups lay low for a while. After the swift victories of the Nazis in Poland, France, and other European countries, the moment seemed inopportune as Hitler's popularity was too high. Further on, there were more plans to oust him but the conspirators were too indecisive to follow through.

As the war began, generals and officers of the Wehrmacht, especially on the Eastern Front, turned a blind eye to the brutal treatment of civilians and prisoners of war, in some cases even participating in war crimes. This pertains to the acts committed by the SS and the Einsatzgruppen of the Security Police and the SD, which murdered civilians on a massive scale (in particular, as part of the “Final Solution to the Jewish Question”), as well as the Commissar Order, which provided for the immediate execution of all captured Red Army political workers as “resistance carriers”, in violation of all existing rules of war.

The conspiracy idea did not resurface until 1942. The new plan evolved into a two-stage operation that included killing Hitler, capturing the main communications, and suppressing SS resistance with reserve troops.

However, the conspirators’ repeated attempts on Hitler's life turned out fruitless. On March 13, 1943, during Hitler's visit to Smolensk, an explosive was planted in his plane, but the fuse did not go off. Eight days later, Rudolf-Christoph von Gersdorff was prepared to blow himself up along with Hitler at the exhibition of captured Soviet weapons at the Zeughaus Museum in Berlin, but the Führer left the exhibition prematurely, and Gersdorff barely managed to deactivate the detonator.

Hitler also managed to survive the bombing on July 20, 1944, at Wolfsschanze (the Wolf's Lair), his Eastern Front headquarters: the briefcase with the bomb exploded under the desk where he was sitting, killing four people but sparing the Nazi leader. Soon Nazi propaganda picked up his catchphrase “a small clique of criminally stupid officers”. This rhetoric had a marked influence on post-war West German society in its assessment of the participants in the Resistance for years to come. For a long time, they were considered traitors to the country who were stabbing its valiant warriors in the back. The Allies were no more interested in a positive image of the German Resistance because it would contradict their thesis of the collective guilt of the German people.

A positive image of the German Resistance would contradict the Allies’ thesis of the collective guilt of the German people

A reassessment of the German Resistance began in the mid-1950s, ushered in by the speeches of leading representatives of West German society. In the 1960s, the pendulum swung in the opposite direction: the assassination attempt on Hitler was now considered a heroic act, and the conspirators were treated as blameless heroes who defended the honor of the German army. It was not until the 1980s that historians painted a more critical picture of the Resistance, pointing out the illiberal, authoritarian, and anti-Semitic ideas prevalent among the conspirators. At the turn of the millennium, the trend climaxed in exposing the active participation of some members of the Resistance in the war of annihilation and the Holocaust.

Quiet clerical resistance: crowded services and sermons

Although neither Catholic nor Protestant churches as institutions were prepared to openly oppose the Nazi government, it was the clergy that essentially became the first major component of the nation's resistance to Third Reich policies, and churches as institutions provided the earliest and most sustainable centers of consistent opposition to the Nazi order.

The beginning of Nazi rule in 1933 brought about issues that turned the church against the regime. Clerics offered organized, systematic, and consistent resistance to government policies that infringed on church autonomy.

As one of the few German institutions to retain any independence from the state, the churches were positioned to coordinate a level of opposition to the government and, in the words of German historian Joachim Fest, more than any other institution, they continued to provide “a forum in which individuals could distance themselves from the regime”.

Christian morality and the anticlerical Nazi policies also motivated many German members of the Resistance and served as the impetus for the “moral rebellion” of individuals in their efforts to overthrow Hitler. Another scholar, Stefan Wolff, writes that events such as the July 1944 plot would have been “unthinkable without the spiritual support of the church resistance”.

Some of Germany's religious leaders were also the harshest public critics of the Third Reich since the government was often unwilling to speak out against them. A high-ranking clergyman could count on popular support from his flock, so the regime had to keep in mind the possibility of nationwide protests should such a leader be arrested. Thus, the Catholic bishop of Münster, Count Clemens August Graf von Galen, and Dr. Theophil Wurm, the Protestant bishop of Württemberg, were able to generate widespread public resistance to the murder of the invalids.

Clemens August von Galen

The churches fought a fierce war of attrition with the regime, garnering demonstrative support from millions of church-goers. Applause for church leaders whenever they appeared in public, increased attendance at events such as Corpus Christi Day processions, and crowded church services were outward signs of a struggle against Nazi oppression, especially in the Catholic Church.

Although the church ultimately failed to protect its youth organizations and schools, it had some success in mobilizing public opinion to change government policy. The British historian Alan Bullock wrote that “among the most courageous demonstrations of opposition during the war were the sermons preached by the Catholic Bishop of Münster and the Protestant Pastor, Dr. Niemöller...» but that “neither the Catholic Church nor the Evangelical Church, as institutions, felt it possible to take up an attitude of open opposition to the regime”.