In today's Russia, the petulant head of the Chechen Republic, Ramzan Kadyrov, is not the only one who demands that his critics apologize on camera. Many weeks after blogger Nastya Ivleeva's infamous “almost naked party,” which attracted a crowd of celebrities dressed (or undressed) in accordance with the theme, guests are still partaking in acts of public penance that have included visits to Russian-occupied territories of Ukraine, where they performed charitable concerts for locals and troops. Much like in Stalinist times, public self-incrimination and criticism are gaining popularity by the day in Putin’s Russia. Emerging in the late 1920s, this genre was originally a social elevator of sorts — before it became the only means of surviving the 1930s’ surge of repression commonly known as the Great Terror.

Content

Self-criticism: from criticizing the authorities to repenting for personal mistakes

Letters of apology and autobiographies

Repenting — or snitching on yourself

The “acts of remorse” in Stalin's last years

Self-censorship

Self-criticism: from criticizing the authorities to repenting for personal mistakes

As a nascent state, the Soviet Union had to build its public discourse from scratch. By the late 1920s, independent or even partially independent media had been eradicated. Joseph Stalin was quickly gaining political weight by eliminating his rivals, which meant fewer debates within the Communist Party. In the resulting setup, orders were sent from the top down, but feedback hardly ever made its way in the opposite direction. In response, the Soviet authorities decided to foster a new genre of public debate, using “self-criticism” as its main tool.

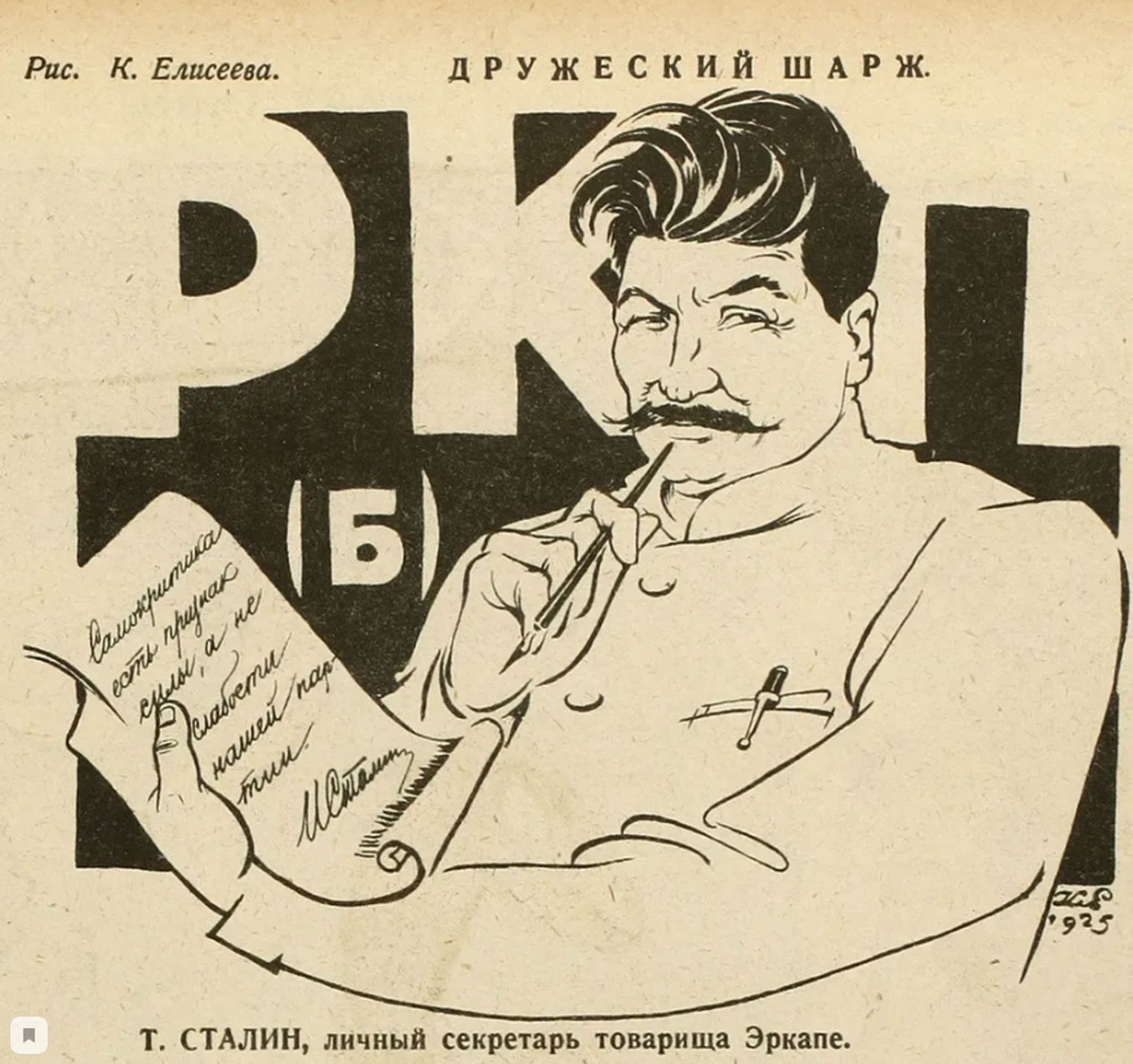

Stalin introduced the term in 1927 during his address at the 15th Convention of the Communist Party: “I am convinced, dear comrades, that we need self-criticism as much as we need air and water... Without self-criticism, our party would not be able to progress; it would not be able to lance our boils or eliminate our pitfalls — and we have plenty of those. We must be frank about it.”

By “self-criticism,” Stalin did not initially mean repenting for one’s own sins but rather “criticizing one’s superiors” — a way for ordinary citizens to provide feedback on their bosses, colleagues, and local authorities without forming political opposition.

Soviet citizens soon picked up on the new practice. A report in Povolzhskaya Pravda, a newspaper in Saratov, read: “Worker participation in the process of self-criticism is on the rise. Whereas in June 1928, the editorial office received 890 letters, in October 1928, we got as many as 2,332. Many reported problems with wages, rations, and workplace discipline.”

The legal status of “self-criticism” remained vague. Formally, public accusations and confessions held no legal force. However, as the Soviet state apparatus became increasingly intertwined with society, answering Stalin’s call to speak truth to power could result in criminal prosecution or other serious implications, including the loss of a job or expulsion from the Communist Party.

Participation in “self-criticism” could result in criminal prosecution, the loss of a job, or expulsion from the Communist Party

The emergence of “self-criticism” was swiftly followed by the genre of public apology. When Soviet writer Yuri Pertsovich was working on his history of the Leningrad Metal Plant, the daughter of one of the plant's Bolshevik heavyweights thought that the author had intentionally downplayed her father's contribution. Pertsovich disagreed but realized that he, the son of a small-time Jewish merchant, had little chance of winning an argument against a revolutionary’s daughter. His dubious origins and education put a bullseye on Pertsovich for all sorts of class-based attacks. Eventually, on July 1, 1933, he criticized his work himself at the conference on the plant's history:

“Due to my narrow understanding of Lenin's words, I only showed how capitalists fought and destroyed each other. Meanwhile, I should have focused on how the proletariat grew and took shape in the class struggle against the capitalists. It does not matter now whether the mistake was deliberate: every mistake you failed to notice becomes a weapon our enemy can use against us.”

Despite his multiple glowing references to Vladimir Lenin and to his critics from the plant — along with his pledge to act henceforth “like a true Bolshevik” — Pertsovich was expelled from the party the very next day.

This was how self-criticism gradually turned into self-incrimination and repentance. The genre implied that the speakers would not only admit their mistakes but also pledge their loyalty to the existing ideology.

The historian Lorenz Erren noted that defendants in Soviet public trials of the 1930s always built their defense around their allegiance to the Communist Party:

“Even confessing to numerous professional or personal blunders, no one dared admit any infractions in the main, decisive issue: loyalty to the Party, its Central Committee, or Comrade Stalin himself.”

Letters of apology and autobiographies

Another form of apologia that emerged in the Soviet Union in the 1930s was a public appeal to the authorities, from local officials to the most senior Communist Party members — including to Stalin himself. Petitioners often pleaded guilty as charged but insisted that the circumstances of their case had been assessed unfairly, or at least incompletely. By appealing to a higher authority as a kind of “court of last resort,” there was at least the hope that someone with the power to intervene in the case might do so.

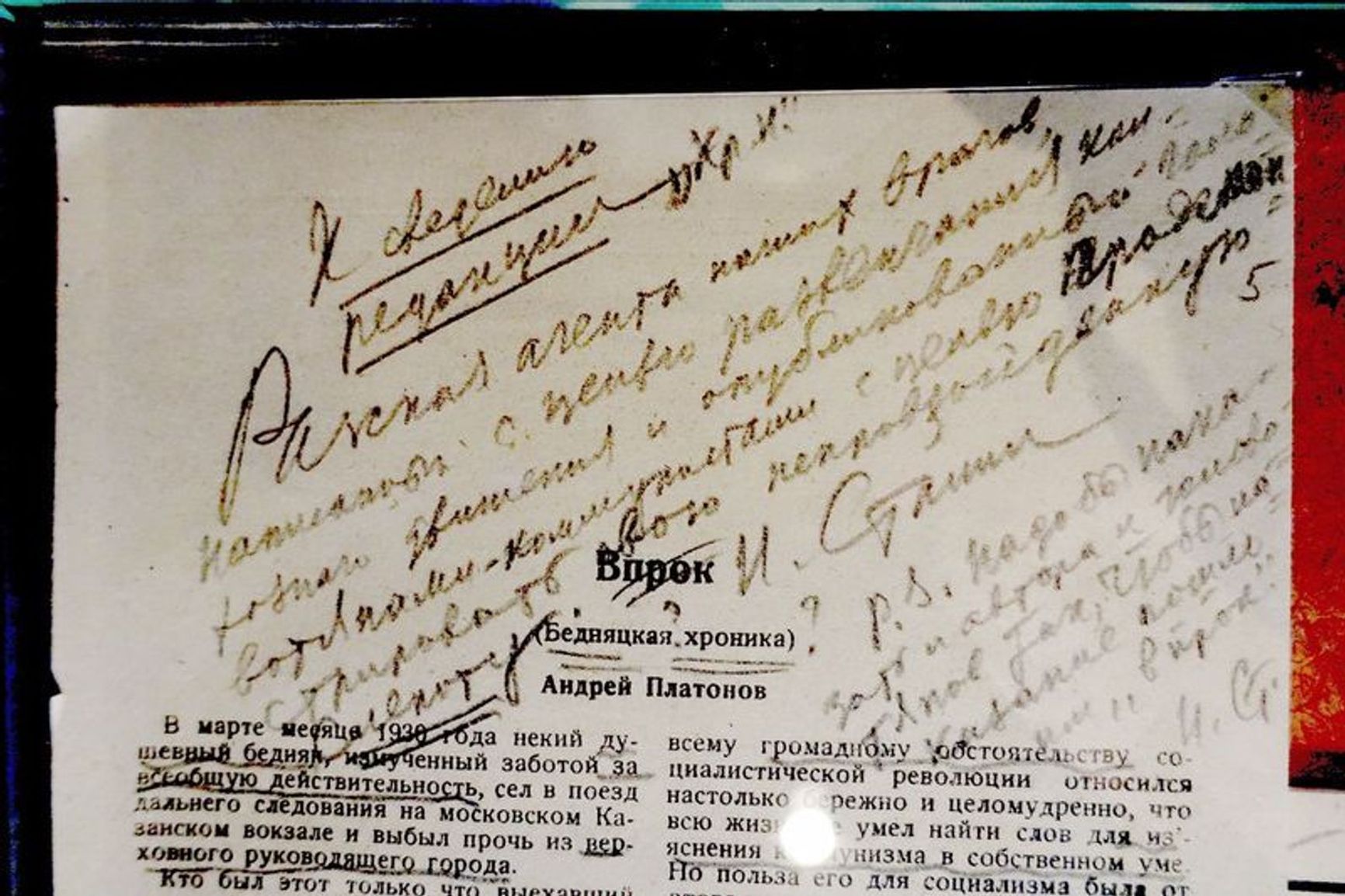

For example, in response to criticism of his short story “For Future Use” (“Vprok”), which exposes the pitfalls of coercive rural collectivization, Andrei Platonov penned a letter to Joseph Stalin in 1931, saying:

“My only concern is to mitigate the harm done by my past activities. I have been working on it since last fall, but now I must redouble my efforts, for the only way to achieve this is by writing something that would redeem the damage done by ‘Vprok.’ Apart from this crucial objective, I will write a statement for the press, confessing the ruinous errors of my literary work — and in such a way that others will be frightened. I will make it clear that any speech that is objectively harmful to the proletariat is a vile act, an act all the more heinous if committed by a proletarian.”

Platonov's story “For Future Use,” a satire on the Soviet practice of agricultural collectivization, invited Stalin's personal wrath on the author and resulted in his harassment by the press

Andrei Kolybalov

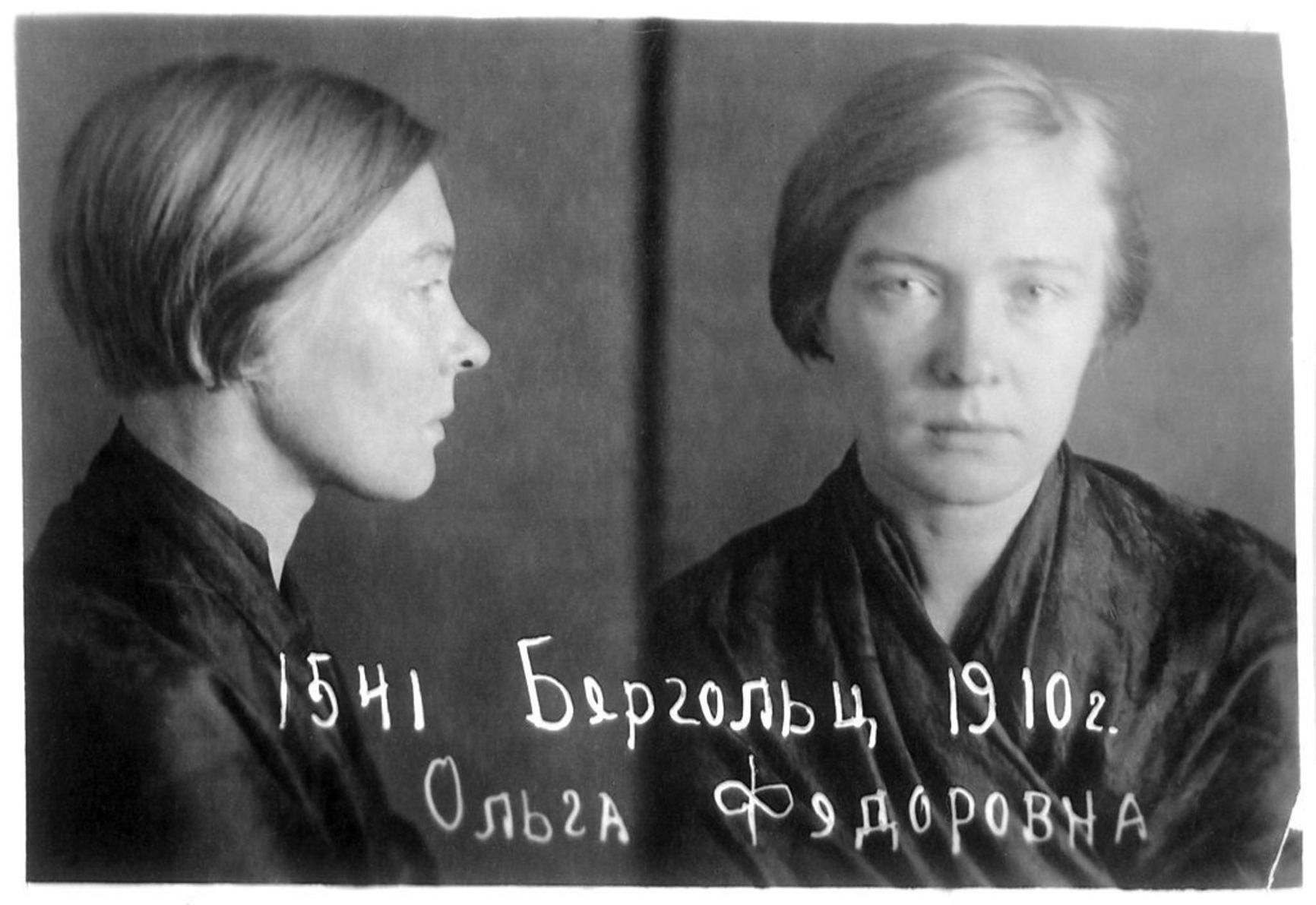

Platonov was not alone. After spending a year in prison on false charges of counter-revolutionary conspiracy, in 1939 Olga Berggolts, a poetess from Leningrad (St. Petersburg), wrote in her diary:

“I had a sudden urge to write to Stalin about the way he is perceived inside a Soviet prison. Oh, what a radiance surrounded his name there! He was the source of such hope for people on the inside that even when I started to think that he knew everything, that it was all his fault, I didn't let myself take that one single hope away from the prisoners.”

Olga Berggolts

Ivan Shemanov, a cultural critic and researcher of Stalin's repression, notes another type of repentance — through autobiographies:

“The working class and its party were to lead mankind to an earthly paradise. From a class perspective, all ‘non-proletarian’ members of society had to publicly clarify the inner change that had caused them to side with the revolution — for instance, in a confessional autobiography. These texts were recited at all sorts of meetings during so-called ‘purges’ or selection of candidates.”

Repenting — or snitching on yourself

The Moscow Trials of 1936-1939, in which some of Lenin’s closest former associates fell under official suspicion, reinforced the use of this new template of repentance to the state. The trials of Joseph Stalin's enemies — Grigory Zinoviev, Lev Kamenev, Karl Radek, Genrikh Yagoda, and Nikolai Bukharin — were not just public. The authorities intentionally published their transcripts, invited Western journalists to attend, and recorded some of the speeches of the accused.

The particulars of how these trials unfolded, however fascinating, are not as important in the context of the present article as the role of guilty pleas and repentance. The defendants’ decision to incriminate themselves eventually led to their death sentences and contributed to further repression.

The defendants’ decision to incriminate themselves eventually led to their death sentences and contributed to further repression

Ivan Shemanov notes that the role of confession in Soviet courts of the 1920s-1950s was constantly evolving: “Until the end of the 1920s, repentance was obligatory for persons of ‘non-proletarian’ origin who wanted to join the [Communist] Party and served as a helpful instrument of personal development and career. The 1930s are more appropriately described by the historian Lorenz Erren, who called the atmosphere in the USSR a ‘Soviet roulette.’

During the Great Terror, the presence or absence of a confession had hardly any bearing on the outcome of the investigation. One can only assume, with sadness, that the earlier the defendant signed a confession, the less physical and mental torture they had to endure.”

Meanwhile, the role of evidence in such public trials was also diminishing. During the Moscow Trials, even state dignitaries had doubts about the court's decision and the proceedings in general. Thus, as future General Secretary Nikita Khrushchev wrote in his memoirs about the firing squad sentence given to former NKVD head Genrikh Yagoda:

“When Yagoda was accused of taking steps to bring Maxim Gorky to death as soon as possible, the arguments were: Gorky liked to sit by the fire and was a frequent guest at Yagoda’s, so Yagoda built large fires to keep Gorky outside so he catches a cold, falls ill, and soon dies. I found it a little incomprehensible. I love bonfires, too, and I don't know anyone who doesn't like them at all.”

The function of public repentance was also changing. While the “self-criticism” of the 1930s might have served as a means of addressing specific problems while allowing for forgiveness and realization of guilt, by the 1950s a lot had changed.

First, defendants more and more often “objectified” themselves. They said that they'd had no intention to cause harm, but their origin (bourgeois roots, for example) or personal qualities had led to fatal mistakes.

Grigory Zinoviev, sentenced to execution during the First Moscow Trial, spoke in his confession about his political role as follows: “I was again becoming the mouthpiece of anti-party sentiment. Subjectively, of course, I did not want to harm the party or the working class. However, I ended up becoming the mouthpiece of the very forces that sought to stop the socialist offensive and wanted to derail socialism in the Soviet Union.”

Second, the admission of guilt did not imply forgiveness — only a chance of survival. Party leader Nikolai Bukharin, who was sentenced to execution at the Third Moscow Trial in 1938, wrote in a petition for clemency: “Inside the country, a broad socialist democracy is developing based on Stalin’s constitution. A great creative and fruitful life is blooming. Give me a chance to make my humble contribution to this life, even from behind bars! I beg you, I implore you: please let me be at least a tiny part of this life!”

The appeal does not even hint at the possibility of redemption, focusing instead on the hope of helping those its author had allegedly harmed.

Unlike “self-criticism,” which aimed to improve the system through regulated critique, “penances” affirmed the existing order and celebrated its accomplishments and victories.

The “acts of remorse” in Stalin's last years

The Soviet Union's participation in World War II slowed down most trials of “internal enemies.” However, public penance made a comeback in the last years of Stalin's rule, which only ended with the dictator’s death in 1953. Politically motivated purges in Soviet academia and culture were euphemized as “debates”: the 1947 “debate on philosophy,” the 1948 “debate on genetics,” and the 1950 “debate on linguistics.”

At first glance, the large-scale philosophical discussion in 1947 had an unlikely purpose: to criticize Georgy Aleksandrov's “History of Western European Philosophy.” The scholar was accused, among other things, of failing to “indicate the class origins” of 48 philosophers out of the 69 he mentioned. In addition, the book was ostensibly written in the “worthless, empty, liberal language of a bourgeois objectivist professor.” Worst of all, the author was accused of “blurring the radical opposition between Hegel's idealist dialectic and the revolutionary materialist, Marxist-Leninist dialectic,” and of “failing to uncover the class limitation of Hegel's dialectic.”

This summary of accusations against Aleksandrov reveals that the charges did not concern his research, but rather his personality — this despite the fact that the author was among the most renowned scholars of the time.

Aleksandrov did not attempt to defend himself but instead agreed with his accusers, thus admitting his intellectual and political defeat. Interestingly, his coyness was rewarded with the post of director at the Institute of Philosophy of the Academy of Sciences.

In other words, although in the 1940s the Soviet state no longer needed even a semblance of popular approval to ruin a person's life, the ritual of repentance and self-criticism retained some of its power. When Georgy Aleksandrov later began to criticize Western trends during the “combat against cosmopolitanism,” he was repeatedly reminded of having committed similar “transgressions” in the past — which meant his credibility (and personal safety) were somewhat compromised.

As historian Konstantin Tomilin notes, in the late 1940s, the Soviet regime ran a campaign to expose “rootless cosmopolitans” and “groups of anti-patriotic physicists,” but “the authorities had a much greater motivation to master atomic weapons than to conduct any ideological campaigns,” so some of the scientists were eventually acquitted despite refusing to admit their guilt.

The authorities had a much greater motivation to master atomic weapons than to conduct any ideological campaigns

Self-censorship

What the Soviet regime promoted as “self-criticism” was essentially a euphemism for self-censorship. Since no one, not even prominent artists or scientists, was immune to the constant threat to personal safety, everyone scrutinized their work for possible ideological “mistakes” — even without instruction. Thus, by her own admission, Stalin Prize-winning writer Marietta Shaginian rewrote 75 percent of her novel “Hydrocentral” for the new edition. Although this book had already been acclaimed in the 1930s, the author did not consider her reputation to be unblemished.

In this context, self-criticism gained a new function: rewriting the Soviet cultural canon. Dmitry Tsyganov, a historian of Russian literature, noted: “Criticism began to be directed against socialist realist texts that were previously considered exemplary and had even been awarded the Stalin Prize.”

Only Stalin's death managed to stop the flywheel of “self-criticism” and repentance. The practice of public trials remained, of course, but by Khrushchev’s time in power an admission of guilt was often enough for the “wrongdoer” to be forgiven. Valery Otyakovsky, a historian of Russian literature, noted that “the development of the dissident movement and the final dilapidation of Stalinist rhetoric techniques allowed the accused to ignore the stage of self-criticism or even try to absolve themselves.”

Ivan Shemanov, a researcher of Stalinist repression, notes that the practice of public repentance could be leveraged by those with “a good command of political language.” Confessing your sins in time meant a chance of survival. However, as the historian emphasizes, a confession “offered no guarantees of salvation because any guarantees would have rendered the act of repentance empty, emasculated to the point of ritual. In the Soviet Union, it did not happen until after Stalin.”

Not only were practices of “self-criticism” becoming decrepit, but their very purpose was also changing. No longer a prelude to criminal prosecution or dismissals, they gradually turned into a tool for mitigating reputational damage. The public discourse that began to be formed in the late 1920s eventually made it possible to use the instruments of the state against the state itself. The never-ending speeches of the “wrongdoers” made it acceptable for them to have a voice in the first place — and hence, the ability to criticize.