Eighty years ago, the Soviet authorities began the deportation of the indigenous population of Crimea. Within just a few days, hundreds of thousands of Crimean Tatars were expelled from their homes and sent thousands of kilometers away. Many did not survive the journey, and countless others grew old and died far from their native Crimea. Today, those who managed to return from exile are once again facing repression from the occupying authorities in Moscow.

Content

Stalin's deportation

“There were thousands upon thousands of people”

Erased from history

“If the Crimean Tatars had been armed back then, Crimea would still be Ukrainian”

Soon after Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea in 2014, trains that once connected the peninsula with Kyiv and other Ukrainian cities only traveled as far as Novooleksiivka station, located just a few kilometers from the Kherson region’s administrative border with occupied Crimea. Novooleksiivka itself is a typical sleepy southern steppe settlement — there is a train station, a few shops, some small private houses lining broken country roads, and hardly a Soviet-era apartment block in sight.

There are countless such places in southern Ukraine. However, Novooleksiivka is special. If you follow the safety rules and walk to it from the station via the high pedestrian bridge over the railway tracks, the town’s special feature becomes immediately visible. Among the metal roofs of one-story houses and the surrounding greenery, not far from the shining golden domes of the local Orthodox church (still of the Moscow Patriarchate), two elegant ivory-colored minarets rise above a mosque built in the eastern style.

The mosque in Novooleksiivka

Although mosques are not uncommon in southern Ukraine, those as grand as the structure in Novooleksiivka are typically found only as far north as Bakhchysarai, the inland old capital of the Crimean Khanate. During the Kurban Bayram holiday in the years following the 2014 occupation, the magnificent mosque in Novooleksiivka would draw in at least five thousand people — most of them Crimean Tatars who either failed to reach their native peninsula after returning from Central Asia in the 1990s or who were forced to flee the Russian annexation.

“You know, this is also our ancestral land. The Kherson region was also part of the Crimean Khanate. We are at home here. And look around — how is this steppe different from the Crimean one? They are absolutely the same,” smiled local resident Bilyal, welcoming guests from Kyiv.

Bilyal was born in Novooleksiivka in the 1980s, a time when Crimean Tatars were still prohibited from returning to the peninsula itself, but they were nevertheless permitted to leave the faraway lands where their entire people had been sent in 1944. In the 1970s, Bilyal's young and ambitious parents had moved from Uzbekistan to Ukraine, intending to settle as close as possible to the ancestral home they had never seen.

Novooleksiivka proved to be the closest populated area to Crimea. By 1989, when Soviet authorities finally permitted Crimean Tatars to return to the peninsula, several thousand who had left the places of deportation were living in the settlement. While some moved to Crimea in the late 1980s and early 1990s, many stayed put. They had already established households and could reach Crimea relatively easily by train or bus.

After 1989, when migration back home finally became possible. Novooleksiivka turned into an unremarkable provincial settlement, barely noticed by the Simferopol-bound passengers whose trains stopped there for a few minutes. The youth, including Crimean Tatars, largely left in search of opportunities in bigger cities. Returning Crimean Tatars headed straight to the peninsula, often unaware of the role Novooleksiivka had played in the fate of those who had yearned to reach their ancestral homeland during Soviet times.

But the special status of the settlement returned after the Russians seized Crimea. Novooleksiivka once again became the closest point to the peninsula, a sacred place for those Crimean Tatars who were denied entry into Crimea by the occupiers and for those who did not dare to enter the illegally annexed region. Several dozen families relocated here from Crimea, fleeing persecution. Every year on May 18, thousands of Crimean Tatars from all over Ukraine came to the settlement to honor the memory of those who did not survive Stalin's deportation of 1944.

Stalin's deportation

The decision to deport the Crimean Tatars was made on May 11, 1944, at a meeting of the State Defense Committee (GKO), an extraordinary body of the USSR that was granted special powers during World War II. The secret order approved that day mandated the resettlement of around two hundred thousand people to the Urals, the northern regions of Russia, Kazakhstan, and, primarily, Uzbekistan.

The initiator of the deportation was the People's Commissar for Internal Affairs, Lavrentiy Beria, whose department was tasked with carrying out forcible resettlements. Officially, the deportation was announced as punishment for the alleged mass desertion of Crimean Tatars from the Soviet army and their alleged active collaboration with the Nazis during the German occupation of Crimea.

Archival data show that the number of deserters and collaborators among the Crimean Tatars was no higher than among other Soviet peoples

However, archival data show that the number of deserters and collaborators among the Crimean Tatars was no higher than that among other Soviet peoples, and few switched to the enemy's side. Nevertheless, the decision to deport was made, and less than a week later — on May 18, 1944 — Soviet authorities began implementing it.

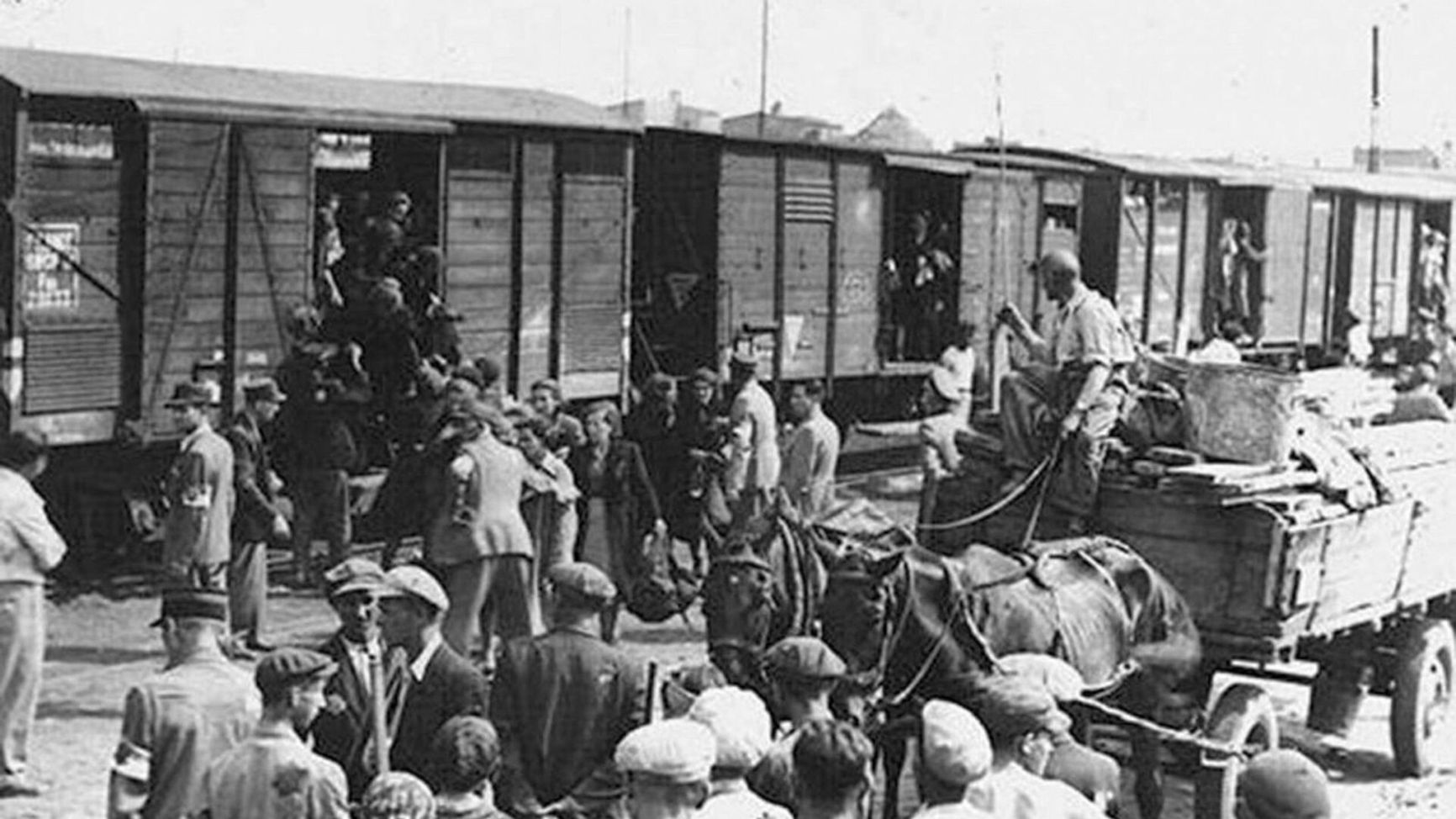

Officially, each exiled family was allowed to take along up to 500 kg of luggage. In reality, however, Crimean Tatars were often driven out of their homes with only hand luggage. Under armed escort, people were taken to railway stations, where they were loaded into already waiting railway cars. The operation was swift. Within three days, about two hundred thousand people were transported out of Crimea.

Trainloads of deportees traveled one after another along the mainline from Crimea through the Kherson region, Donbas, and the southern regions of the RSFSR before making their way further into Central Asia. People were transported in cattle cars. No fewer than eight thousand Crimean Tatars died en route — from thirst, overcrowding, and the inevitable outbreaks of infectious diseases that accompany such unsanitary conditions.

No fewer than eight thousand Crimean Tatars died en route from thirst, overcrowding, and outbreaks of infectious diseases

“There were thousands upon thousands of people”

Such a cattle car — with creaky wooden floors and wooden walls that were dangerous to touch for fear of splinters — was displayed every year on May 18 on the spare railway tracks near Novooleksiivka. Here, the convoy of cars that each year wound its way through the cities and villages along the administrative border with occupied Crimea in order to mark the Day of Remembrance for the Victims of the Crimean Tatar Deportation would come to a stop.

The convoy usually started from Henichesk — the local district center. A mourning rally with officials from Kherson and Kyiv was held on the central square in the morning, after which cars decorated with Ukrainian and Crimean Tatar flags — bearing a golden tamga (seal) — would head to this cattle car.

“I remember how people were transported in such cars through our station. There were so many trains from Crimea with deportees that they stood on the tracks for hours waiting for a chance to move on. I was still a girl, not even sixteen. My mother, brothers, and I would go to the railway at night to bring water and bread. Maybe we saved someone's life. Although how much bread could we bring? And there were thousands upon thousands of people,” recounts an elderly local resident who suddenly volunteered to speak at the temporary monument.

She speaks in a melodic Ukrainian language that seems to have no consonants. She starts her story calmly but soon becomes noticeably nervous, and tears appear in her eyes.

“It's all cursed Russia. It didn't let people live then, and it doesn't let them live now. What did we ever do to you that you won't leave us alone,” she almost shouts, waving her small elderly fist towards occupied Crimea.

She is comforted by Crimean Tatar women who give her water, hug her, and wipe the tears from her face with handkerchiefs. It is 2017. The weather is already summer-like — warm and sunny. Locals dressed as Soviet NKVD officers are sweating in the heat in their thick cotton uniforms. They participated in every memorial anniversary. Not everyone found this theatrical part appropriate, but it quickly became a tradition.

Shot from Haytarma (2013), a movie about the deportation of the Crimean Tatars

The imam of the Novooleksiivka mosque and an Orthodox priest who arrived from Henichesk take turns leading prayers for the repose of the souls lost during the deportation or in exile. After the prayers, there is a minute of silence. Only the flags clashing noisily against each other in the strong steppe wind continue to move.

Erased from history

In the first years after the deportation, between 20% and 46% of Crimean Tatars perished. The people’s literature, artworks, and musical instruments were left behind in the homes from which they were expelled. The printing of books, newspapers, and magazines in the Crimean Tatar language ceased. Official performances in Crimean Tatar were no longer staged, and the language was not taught in schools or universities. Most of the old names of cities and villages in Crimea were replaced with new ones, bearing no resemblance to the original Crimean Tatar toponyms. Its indigenous people were being erased from the peninsula's history.

In a book titled Legends of Crimea, published in Simferopol in 1961 after Stalin's death and the public condemnation of the myriad crimes committed during his rule, Crimean Tatars are not mentioned even once. When the true people of the peninsula do appear on its pages, they are simply called “Tatars,” and are portrayed as outsiders and invaders. In one of the legends, a local resident with the name Maria even opposes “hordes of conquerors-nomads.” However, the Crimean mountain mentioned in the text suspiciously bears the non-Slavic name Demerdzhi.

In a book entitled Legends of Crimea published in Simferopol in 1961 Crimean Tatars are not mentioned even once

In the year this book was published, many of the peoples deported during the war — Chechens, Ingush — had already been rehabilitated and were returning from exile. But not the Crimean Tatars. Only in 1967 did the Soviet authorities officially lift the accusations of collaboration with the Nazis from the entire people. However, the Kremlin still did not allow Tatars to return to their homeland.

“The Tatars, who previously lived in Crimea, have settled in the territory of Uzbekistan and other Soviet republics,” Soviet officials offered in an attempt to explain their refusal to allow Crimean Tatars to return home.

Naturally, this was a lie. Bilyal, born in Novooleksiivka, his parents, who were born in distant Uzbekistan, and thousands of other Crimean Tatars, when asked about their geographical origins, would invariably name the city or village from which their fathers and grandfathers had been deported in 1944.

Shortly after Stalin's death, Crimean Tatars began the struggle to return to their homeland, and their national movement was born. The Soviet authorities repressed the most active participants. Mustafa Dzhemilev, deported to Uzbekistan as an infant, sought starting from his teenage years permission from Communist Party officials for the Crimean Tatars to return home. The authorities, in turn, declared him an anti-Soviet and a provocateur. Dzhemilev was tried seven times and spent fifteen years of his life in camps and prisons.

Hundreds of other Crimean Tatars and their supporters of different ethnic origin went through prisons. Soviet dissident General Pyotr Grigorenko, who had previously faced trouble with the authorities due to his fight against repression, was arrested in the 1970s and imprisoned by the KGB for supporting the Crimean Tatars in their struggle to return to their homeland.

Despite these efforts, it was not until 1989 that the authorities allowed the Crimean Tatars to return home — and even then, not without restrictions. They could not claim the property confiscated in 1944, could not register in the major cities of the peninsula, were refused employment, and were largely feared and avoided. Perhaps Soviet propaganda, which for years had depicted the Crimean Tatars as bloodthirsty savages, had had a last effect. Or perhaps the new inhabitants, who appeared on the peninsula since 1944, feared they would be asked to vacate the homes of the deported. But these fears were unfounded.

It was not until the late 1980s that the authorities allowed the Crimean Tatars to return home, albeit with many restrictions

“Thank God, we managed to avoid this [conflict]. Kyiv and the official authorities attribute this achievement to themselves, boasting about the wise policy they supposedly pursued, but the truth lies elsewhere. The main reason is the principles of non-violence developed at the beginning of the Crimean Tatar national movement. In all acute situations, we threw our efforts into preventing bloodshed,” explained Mustafa Dzhemilev back in 2011, by which time he already held the unofficial — but very honorable — title of leader of the Crimean Tatar people.

At that time, Dzemilev was also warning about the danger of growing pro-Russian sentiments on the peninsula among ethnic Russians brought in after the deportation, as well as among the Russified local Ukrainians. He called on pro-Russian Crimeans to “reunite with their homeland” within its internationally recognized borders, and not to invite Russia into Ukrainian Crimea.

“If the Crimean Tatars had been armed back then, Crimea would still be Ukrainian”

“When the Russians appeared in Crimea, I expected that we would be given weapons — that a KAMAZ truck with rifles would arrive in the Crimean Tatar neighborhood, as it did in Kyiv's Obolon in February 2022, and each of us would be given a weapon to drive out the occupiers. But it didn’t arrive. If the Crimean Tatars had been armed back then, Crimea would still be Ukrainian, and there would have been no war. We would have nipped it in the bud,” says Akhmet, a former Yalta businessman and now a soldier in the Armed Forces of Ukraine.

Akhmet and his family left the peninsula a few months after the Russians took it over. He abandoned his business and home, moved to Kyiv, and started over. In 2017, he was in Novooleksiivka and even marched in the front row when several hundred Crimean Tatars decided to walk to the administrative border of Crimea on the day of mourning. The occupiers then gathered dozens of armed soldiers at the checkpoint and blocked the road with trucks. A Russian officer and provocateurs hiding behind the soldiers with cameras insulted the unarmed people standing opposite them and chanted slogans like “Crimea is Russia” and “Tatars go home.” “I think I realized back then that we would have to fight them. That they wouldn't just calm down,” Akhmet admits.

When Russia launched its full-scale invasion, Akhmet had several young children on his hands, meaning he was not subject to conscription and could have stayed home. But he volunteered in the first days of the war. He says that otherwise, the Crimean Tatars would lose their home again. And he is not exaggerating.

Russia, having declared illegal any Crimean Tatar organizations outside its control, has launched a real hunt for “religious extremists.” This creates a situation for the indigenous population of Crimea — one that the Crimean Tatars themselves describe as hybrid deportation. While they are not forcibly herded into cattle cars, they are also not allowed to live in peace. Its people constantly fear arrest, searches, and accusations of terrorist connections.

Russia creates a situation for the indigenous population of Crimea that the Crimean Tatars themselves describe as hybrid deportation

Since the Russian occupation of Crimea began in 2014, approximately one in every six Crimean Tatars — around 50,000 people — left the peninsula. Of them, at least several hundred resettled in Novooleksiivka, the first station outside Crimea where, the inhuman trains carrying their ancestors deported by Stalin once passed.

On February 24, 2022, the day of Russian launched its full-scale invasion, units advancing from Crimea seized control of the settlement. Since then, it has remained under occupation, with its residents, including Crimean Tatars, held hostage by the occupiers once again. The persecution of Crimea's indigenous people, which commenced on May 18, 1944, persists to this day.