Alexei Navalny's autobiography, published in October, demonstrates how a figure committed to fighting for ethical ideals could emerge from the toxic, hypocritical, and corrupt environment of Russian politics. Navalny’s memoir effectively became his last — and, perhaps, his most important — investigation. Cultural scholar Andrey Arkhangelsky, who was among the first to read the book, tells the story of Navalny’s story.

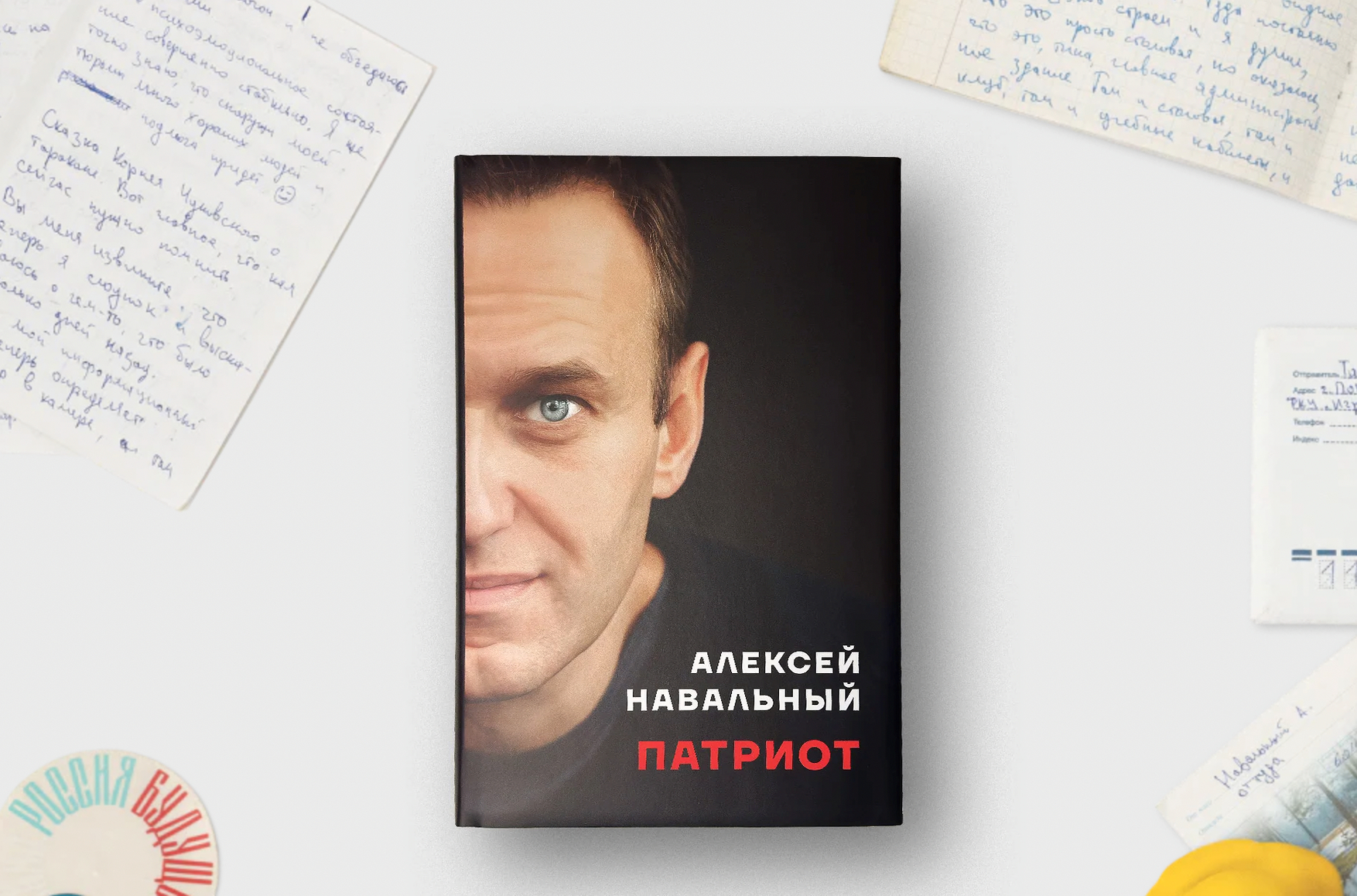

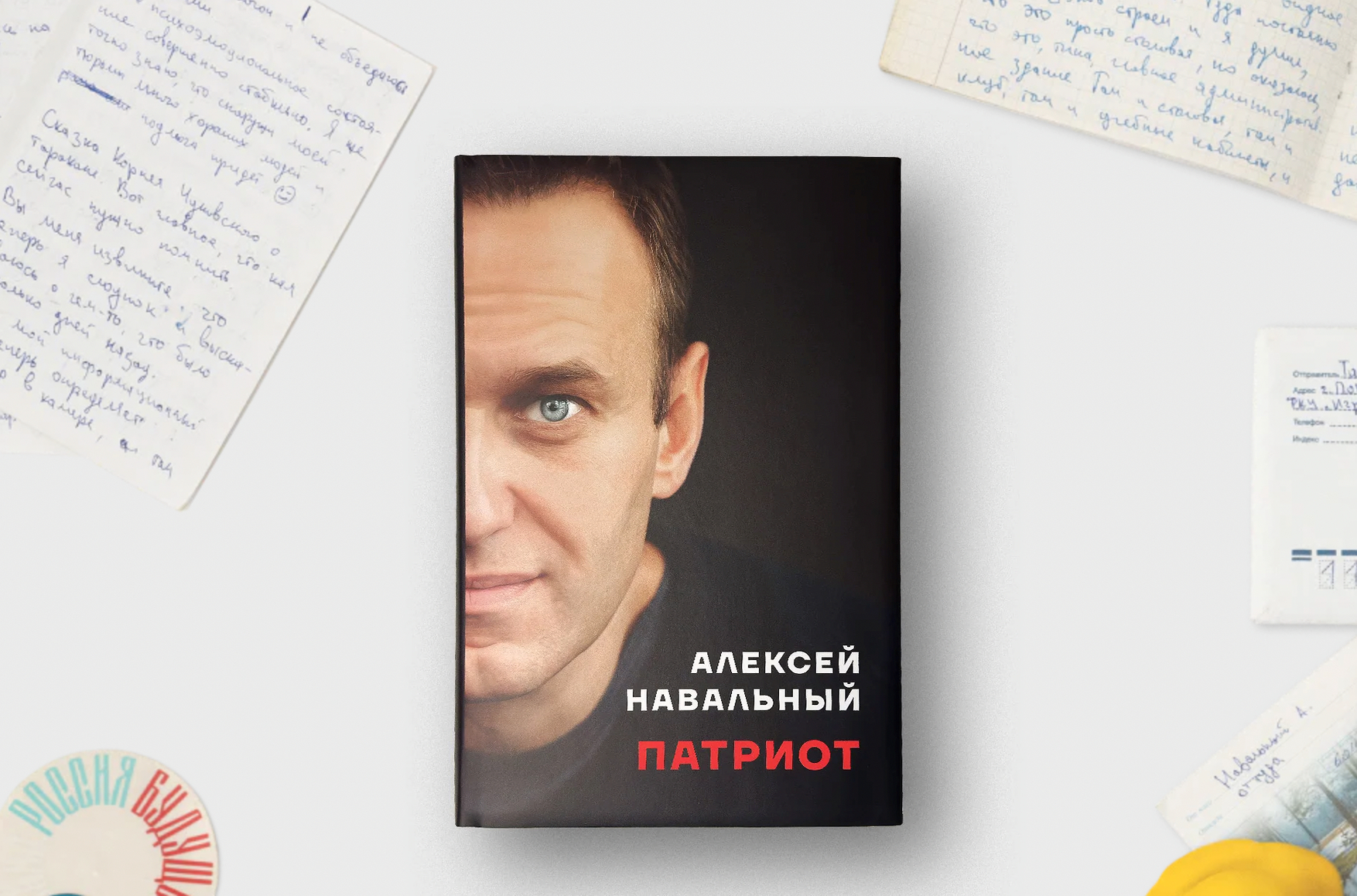

The memoirs of Alexei Navalny, titled Patriot, have been published worldwide. The English version has already become a bestseller on Amazon, while Russian-speaking readers have access to the text thanks to publishers in Lithuania. The book is divided into two parts: an autobiography, in which Navalny recounts his life before January 17, 2021, when he was arrested at passport control after returning to Russia, and a diary, in which he documented prison life and customs. The entries were compiled by his widow, Yulia Navalnaya, based on Navalny’s notebooks and prison messages transmitted through his lawyers and published on Instagram.

The autobiography, about 300 pages long, is partly written in a personal, thoughtful, and deliberate manner, while other sections are dictated. The contrast is noticeable. One might expect a tragic tone throughout, but if readers take a step back, sections of the text resemble a kind of Politics for Dummies. As far as I'm concerned, there were still some gaps in Navalny's biography — not in terms of facts, but in the emotional journey that must have accompanied them. And yet, the main question remains: how did someone with Navalny’s temperament and talent for public life emerge, seemingly from nowhere, outside and above the political tradition of his time and place?

Navalny's response suggests there's no mystery, and you find yourself thinking, “Of course, why didn’t I realize this sooner?” It all seems so plain and simple.

Alexei, born in 1976, spent his summers with relatives in Ukraine, near Chernobyl, where most of his Ukrainian side of the family lived. He fondly describes this time as his “Ukrainian paradise.” While his family spoke Russian at home, they used Ukrainian in his grandmother’s village. This everyday bilingualism, which psychologists say has a significant impact on a child’s development, exposed Navalny to the idea that there are “others” — people who are different, or, at least, not quite the same as you. Even lighthearted conversations highlighted this difference and sense of crossing boundaries. “Lyosha, are you Russian or Ukrainian?” they would ask each time he visited. Navalny preferred to avoid giving a direct answer, likening the question to being asked, “Who do you love more: your dad or your mom?” It’s important to note that these conversations took place in Soviet Ukraine. While Putin’s propaganda today insists “there is no difference,” we can see that even in the late USSR, that “difference” was very much acknowledged.

Psychologists say everyday bilingualism has a significant impact on a child’s development

When Navalny was 10 years old in 1986, his “Ukrainian paradise” abruptly ended when the Chernobyl nuclear power plant exploded nearby. His relatives, along with 160 other villagers, were forced to evacuate. On TV, the authorities constantly downplayed the danger, claiming there was “no threat,” but young Navalny witnessed firsthand how starkly reality clashed with propaganda. His relatives were allowed to take only the bare essentials, and for Soviet people, “belongings” were something special. They spent their lives accumulating them, as new things were hard to come by in a society where consumer options were severely limited. This material loss added another layer of tragedy. From it, one can almost trace the origins of Navalny’s characteristic tone — the fury and passion with which he would later denounce “lies, liars, falsehoods.” That energy, seemingly inexplicable at times, likely has its roots in the Ukraine of his Soviet childhood.

In that same childhood, Navalny often overheard Soviet officers — his father's colleagues — “talking politics in the kitchen.” At the time, this meant something fairly innocuous: grumbling about empty store shelves and exchanging news heard from foreign radio broadcasts. They would even cover the phone with a pillow while doing so. In the USSR, “politics” meant muffled kitchen conversations. Decades on, the Putin regime has likewise sought to keep politics confined to whispered discussions between a few people, a secretive activity disconnected from ordinary life. Politics in this world was something foreign, only to be handled furtively and then quickly put away. Navalny the political figure was born from a simple yet radical decision: to transform politics from being a vague, distant concept into something real and accessible to everyone. No longer was it to be borrowed in secret; it instead became something people could openly claim as their own — openly and without asking for permission.

Navalny makes it clear that he gained his first political insights — and even his initial “capital” — simply by observing the world around him. He didn’t have to do anything extraordinary; it was enough to look at life with open eyes. He describes how bribery at the law faculty of RUDN University (formerly Patrice Lumumba University), where he studied, was practically woven into the fabric of the educational process. In his autobiography, Navalny candidly admits for the first time that in the 1990s he was a liberal, a fervent admirer of Yeltsin, and a strong supporter of market reforms. However, everything changed after an incident involving customs clearance when Navalny imported his first car from Germany. He recounts standing in line for days at a series of low windows, submitting documents that required ever more supporting documents, with groups of young men always nearby, offering to “resolve” everything with a bribe. The peak of this bureaucratic nightmare came with a visit from Yeltsin’s press secretary, Yastrzhembsky, who, as Navalny describes things, didn’t just climb the steps of the customs office but “floated” up them. It was at that moment that everything fell into place, revealing how the system truly worked. “A sober look at the Yeltsin era,” Navalny writes, “shows a sad reality that explains Putin’s rise to power: there were never any real democrats, much less liberals, in power in post-Soviet Russia. [...] They were all just a bunch of [...] party functionaries” who had temporarily adopted democratic rhetoric. Navalny’s deep disdain for the 1990s, which he has written about even from prison, goes so far as to describe Putin as a natural continuation of Yeltsin. This fury is explained by a simple psychological truth: we criticize with the most passion the things we once believed in, and which we were mistaken about ourselves.

There were never any real democrats, much less liberals, in power in post-Soviet Russia

As you read, you gradually realize that Navalny’s childhood and youth (spanning the late 1980s to early 1990s), along with his habits and interests, are strikingly typical for his generation. Even his choice of favorite films and rock bands is entirely conventional — there’s no Aquarium or Zoopark, as such a proclivity would represent a level of sophistication outside the mainstream. Instead, it’s the popular film Assa and bands like Alisa and DDT. And then it hits you: Navalny's profound normalcy is actually his strength. He even writes about his “ordinary” appearance, which for some reason led law enforcement officers to see him as “one of their own” for a long time (perhaps a reflection of his childhood in a military town?). Navalny himself described this existence as “a nerd pretending to be a superhero.” In truth, the generation that grew up during perestroika should have been a driving force for progress in the 2000s — it would have been logical for those who experienced more freedom than previous generations to push the country forward after truly coming of age themselves. The path that led Navalny to join the Yabloko party in the early 2000s and later enter independent politics seems perfectly natural. What’s actually abnormal is that Navalny’s progression was so unique — that despite the formative experiences of his generation, politics stopped being seen as normal. According to Navalny, it’s his own peers — now in their 50s — who form the core of Putin’s voter base.

As you move into the second part of the book, the prison diary, it’s hard to shake the feeling that you’re reading letters from beyond the grave. In March 2022, Navalny writes, “I will spend the rest of my life in prison and die here” (there are no entries for 2023 or 2024). It’s likely that Navalny understood Putin’s psychology better than anyone. He returned to Russia on January 17, 2021, but once the war began, everything changed. Navalny likely realized then that the trap had fully closed. War, after all, is a way of eliminating any path for retreat. It’s a deeply Russian mentality — the psychology of extremes. With no other options, life somehow feels easier. In this sense, the two Russian political opposites — Navalny and Putin — are paradoxically similar. And in these new circumstances, Navalny could only play his final role with dignity. His conversation with his wife during a prison visit during the first month of the war reads like a scene from a tragic film: “I whispered in her ear, 'Listen, I don’t want to sound dramatic, but I think there’s a good chance I’ll never get out of here. Even if things start falling apart, they’ll take me out at the first sign the regime is crumbling. They’ll poison me.' She nodded calmly and firmly, 'I know,' she said. 'I’ve been thinking the same thing myself.'”

At first, Navalny jokes about his circumstances, staying “above the situation.” This is one of his tactics — breaking down the layers of absurdity. For instance, sharing bread or an apple with cellmates is a violation of the rules, even if the bread is state-issued. Making tea or coffee requires permission. And then there's the constant noise: music blaring in the cell or the TV running non-stop. The rare silence during the 10-minute outdoor walks feels like an incredible relief. While reading, you can’t help but think about how hermetically sealed Putin’s system is. The brain-numbing background noise in prison mirrors the constant soundscape in public spaces across Russia, from cafés to offices — it's just a prelude to the soundtrack of the cell. “Educational work” for prisoners, Navalny writes, is nothing more than “seven people grimly watching Ivan Vasilievich Changes His Profession,” a popular Soviet-era comedy in which Ivan the Terrible is transported through time to 20th century Moscow.

To make more productive use of his time, Navalny keeps a meticulous diary, cataloging the idiocy he observes. It is a way of playing a mental game with himself and his surroundings. His entries are marked by a tone of irony — including self-irony — that persists until the very end. But gradually, the severity of his situation seeps into the narrative. The judges’ new sentences begin to accumulate: 2 years and 8 months, then 9 years, and finally 19. In his entries, Navalny begins to use words that might be best to transcribe rather than to translate, such as pizdetz. His back starts to give out, his legs go numb, and then comes the hunger strike. Every famous political prisoner has had their own way of fighting against time. At one point, Navalny is left with only A Brief History of England, which he reads intently, trying to puzzle out — without googling — who won the War of the Roses. He even draws graphs and diagrams of the two dynasties on a piece of paper, but the guards, misunderstanding his intent, assume he’s hatching another plot to destroy Russia.

The last page of Alexei Navalny's book

At first, before the initial sentencing, Navalny’s prison life was still somewhat bearable — there were times when the fridge was full, and you could even make a salad. But gradually, like shrinking shagreen leather, life becomes thinner, more constrained. The diary, in essence, chronicles isolation. Navalny has no one to truly “talk” to except God (and his lawyers, of course). Yet he writes about his faith without excessive sentimentality. For him, God is present in actions and thoughts, in everything — including politics. This connection between faith and politics is one of Navalny's most significant contributions. In his courtroom speeches, a courtesy given to the convicted, what stands out most is how he intertwines religion, universal ethics, and politics. In his biography, Navalny mentions becoming a believer after the birth of his daughter. In his last closing statement, he quotes philologist and cultural scholar Yuri Lotman: “As conscience without developed intellect is blind, so intellect without conscience is dangerous.” In today's Russia, it is the triumph of conscienceless intellect that holds power. Navalny’s conclusion is that ethics — more than any ideology — is the foundation for both democracy and capitalism. This marks a striking epilogue to his political career. Having been a man of action all his life, Navalny emerges as a profound thinker. The longer and more unjust his sentence, the deeper and more significant his reflections become. And in this transformation, there is a kind of victory — over the judges, over the executioners, and over the darkness that surrounds him.

* * *

After his poisoning in 2021, Navalny did something extraordinary — he launched an investigation into his own would-be killers. Now, in prison, he realizes he is once again face-to-face with them, only this time they won’t miss their chance. They observe him through the peephole, like predators sniffing and watching their prey before striking. There is an undeniable element of sadism in this, for his would-be killers are sadists above all. But the act of watching him through the peephole also carries something more — something mystical, even archaic. It is as if those observing him, along with whoever ultimately receives the watchers’ reports, do their work with a primal, cannibalistic instinct — as if they seek to absorb for themselves the waning strength of their nearly defeated enemy.

“Inside, there’s a table with eight chairs (all bolted to the floor), and on the wall, a massive mirror. Behind the mirror, there are probably people watching me at this very moment. I feel an overwhelming urge to sneak up to the mirror and then jump at it with the most terrifying expression I can muster,” Navalny writes in an entry from January 21, 2021, when he was taken to see a “psychologist” in prison.

Navalny, in his own way, plays a deadly game in return. He observes the observers. By keeping his diary, he leaves behind what could be seen as his final investigation — a record from beyond the grave chronicling the mundane plot of his murderers.