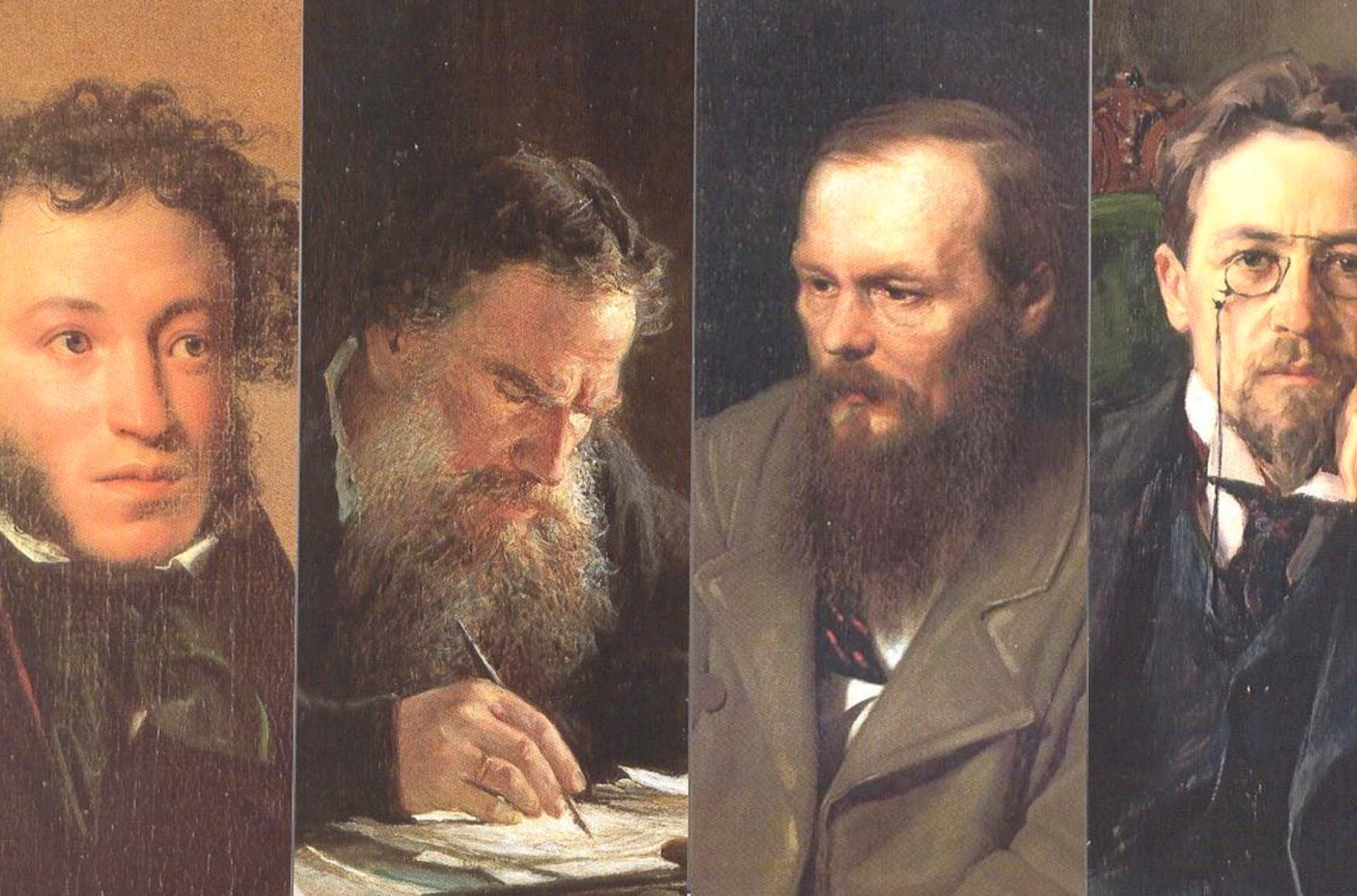

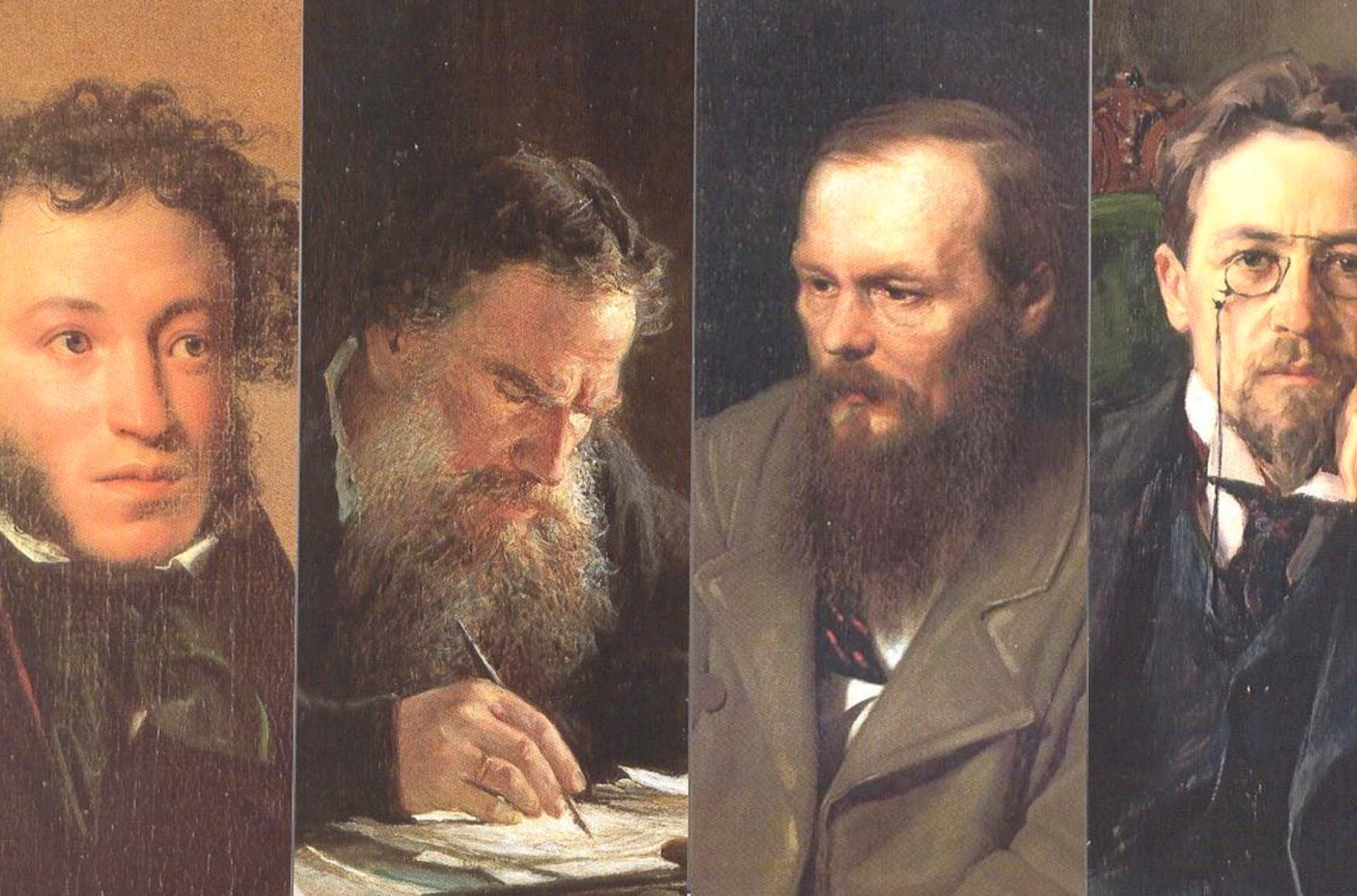

As Pope Francis said the other day, the cruelty of Russian soldiers in Ukraine is not inherent to the Russian nation “because the Russian people – this is a great nation; this is the [cruelty] of mercenaries, soldiers who go to war as an adventure. I prefer to think of it this way because I have high esteem for the Russian people, for Russian humanism,” the head of the Catholic Church concluded. He also recalled the Russian classic author Fyodor Dostoevsky, who is still widely read in the West. According to the Pope, Dostoevsky “to this day inspires Christians to think of Christianity”.

Largely perceived as an attempt to exonerate the aggressor, Francis’ words sparked a heated debate in Ukraine and beyond. Catholic Poland and Lithuania responded with subdued clamor. These two countries were faced with cognitive dissonance: unable to subject the head of their church to harsh criticism, they were still reluctant to agree. Thus, the fact-checking team of Lithuanian national television penned a major article that mildly criticized the Pope and offered a breakdown of why Dostoevsky was not a humanist, after all. The authors touched upon the legacy of a few other authors:

«Other Russian writers, in particular Leo Tolstoy, also followed the path from free thinking and anti-governmental views to praising the empire. Like another Russian classic Mikhail Lermontov, Tolstoy personally participated in the Russian Empire’s colonial wars. Lermontov's works are also imbued with a colonial attitude toward the peoples of the Caucasus and imperialism.”

However, the latter statement is factually incorrect: Leo Tolstoy could not have gone from anti-governmental views to celebrating empire for the sole reason of not advocating either stance at any stage of his literary evolution. On the contrary, Tolstoy consistently promoted anti-militarist views throughout his entire life. In his works, war is not the realm of courage or glory but a source of existential horror, which is especially vivid in his novel War and Peace. Even earlier, in Sevastopol – a reflection on young Tolstoy’s experience as “a war correspondent in Crimea”, in modern terms, – he wrote:

“One of two things: either war is madness, or, if men create this madness, they are certainly not the rational beings that we for some reason think they are.”

(Translated by Joe Fineberg)

Mind you, these words were published in full, without censorship! Inseparable from the Russian Orthodox Church, the Russian government was indeed at odds with the elderly Count Tolstoy for his original interpretation of the Gospel, but his spiritual quest can hardly be called “anti-governmental”.

If we were to determine Tolstoy's degree of “imperialism”, we cannot overlook Hadji Murad, which may well be the most anti-colonialist work in the entire Russian literature. At the same time, Tolstoy was more interested in the psychological perspective, the empathy you feel for someone who is technically your enemy. He always placed himself outside the political dimension by choice, even when it came to publishing in journals – unlike authors like Ivan Turgenev and Nikolai Nekrasov, who formed cliques and associations.

Leo Tolstoy’s Hadji Murad may well be the most anti-colonialist work in the entire Russian literature

Mikhail Lermontov is hardly an example of an imperialist or colonialist either, having been exiled to the Caucasian War in 1837 for the poem he wrote on the death of Alexander Pushkin, causing Nicholas I’s displeasure.

So, apart from a handful of 18th-century odes, similar eulogies written for Joseph Stalin, and maybe The Scythians by Alexander Blok (published in 1918 and initially conceived as a “slap in the face”), no Russian literary masterpiece has ever glorified the government, the head of state, or the empire as a concept. Admittedly, even in Alexander Pushkin's times, the emperor had sycophants like Faddey Bulgarin, and then there were Soviet-era “industrial” novels, but neither went down in history.

In all, the corpus of Russian literature, even if we only take the texts from the school curriculum, is so vast that a knowledgeable enthusiast can find enough quotes and examples to support any narrative.

Are you after proving that Russian literature consistently diminished and insulted Ukraine and Ukrainians? Start with a quote from Alexander Pushkin's Poltava, where traitor and “foreign agent” Mazepa speaks of Ukraine as an independent power:

We’ve spent some time devising plans,

And now they’ve reached a boiling point.

A fortunate hour is upon us;

The time for glorious battle nears.

For far too long we’ve bowed our heads,

Without respect or liberty,

Beneath the yoke of Warsaw’s patronage,

Beneath the yoke of Moscow’s despotism.

But now is Ukraine’s chance to grow

Into an independent power;

Defying Peter, I will raise

The bloody banner of our freedom.

(Translated by Ivan Eubanks)

One could also recall the all-too-familiar poem To the Slanderers of Russia, which Alexander Pushkin wrote upon his return from exile as he was trying to make peace with Nicholas I and adapt his earlier liberal views to the new reality after the Decembrist Revolt of 1825.

‘Tis but Slavonic kin among themselves contending

An ancient household strife, oft judged but still unending,

A question, which, be sure, ye never can decide.

(Translated by Thomas B. Shaw)

The picture would be incomplete without a couple of snobbish, offensive remarks about the Ukrainian language from Ivan Turgenev's Rudin:

“But is there a Little Russian language? Is it a language, in your opinion? an independent language? I would pound my best friend in a mortar before I’d agree to that.”

(Translated by Constance Garnett)

Mikhail Bulgakov includes a similar taunt in The White Guard, his 1925 novel set in Kyiv:

“The day before yesterday I asked that bastard Kuritsky a question. Since last November, it seems, he's forgotten how to speak Russian. Changed his name, too, to make it sound Ukrainian. Well, so I asked him: what's the Ukrainian for ‘cat’? ‘Kit’ he said. All right, I said, so what's the Ukrainian for ‘kit’? That finished him. He just frowned and said nothing. Now he doesn't say good-morning any longer.”

(Translated by Michael Glenny)

As a cherry on top, you could recall Brodsky's On Ukrainian Independence:

We’ll tell them, filling the pause with a loud “your mom”:

Away with you, Khokhly, and may your journey be calm!

Wear your zhupans, or uniforms, which is even better,

Go to all four points of the compass and all the four letters.

It’s over now. Now hurry back to your huts

To be gang-banged by Krauts and Polacks right in your guts.

It’s been fun hanging together from the same gallows loop,

But when you’re alone, you can eat all that sweet beetroot soup.

(Translated by Artem Serebrennikov)

What we get is a simplistic, black-and-white narrative of how Russian literature has always looked down on Ukraine and taught its readers to do just that. However, examples also abound for whatever other narrative you wish to construct. For one, Russian literature has a long-standing tradition of pacifism and humanism. Take Nikolai Rostov from Tolstoy's War and Peace in his very first battle when he was ordered to set towns on fire. Or Nikolai Nekrasov's pacifist poem that was born in the last months of the Crimean War in 1855:

When learning of the tolls of war,

Of yet another battle victim,

'Tis not his wife, nor comrades, nor

The very hero whom I pity...

Alas! Time will console the wife,

Fraternities – forget their member.

But for as long as 'tis alive,

One soul will constantly remember.

Amongst our hypocritic cries,

And all banal, prosaic tears,

Just one I managed to descry

Which is all-holy and sincere –

'Tis in the mourning mother's eyes.

She can forget her son, who lies

Beneath a sodden, bloody hillock,

No better than a weeping willow

Can make its drooping branches rise...

(Translated by Alexander Givental)

Alexander Pushkin, too, has quotes of a completely different nature: “When peoples, having forgotten discord, come together as a family...” (“He Lived Among Us...”, a poem dedicated to Adam Mickiewicz)

So does Lermontov:

I thought: how pitiful Man is,

What does he want!... Clear skies,

Beneath, sufficient room for all,

Yet, endlessly and vainly,

He’s seeking war – for what?

(Translated by Viktor Postnikov)

In 2022, many recalled Yevgeny Yevtushenko’s poem Do Russians Want War? The many references to Ukraine in his works also have more than one interpretation.

We could even return to the aforementioned Mazepa, the Ukrainian leader from Alexander Pushkin's Poltava. Technically an antihero, he is nevertheless fighting for his motherland’s freedom, which makes him a romantic figure. He explicitly articulates the idea that Ukraine needs independence – for the first time in the Russian literary tradition!

On another note, Russian authors have consistently depicted Ukraine as a very special place, a drastic contrast from drowsy Moscow and depressive Saint Petersburg. Every reader knew that Ukraine was a vibrant land, bustling with life, home to freedom-loving people, who are so different from Russian peasants.

This is exactly the impression one gets from Nikolai Gogol's Ukrainian stories, in which the author lovingly describes his native land:

“Do you know a Ukraine night? No, you do not know a night in the Ukraine. Gaze your full on it. The moon shines in the midst of the sky; the immeasurable vault of heaven seems to have expanded to infinity; the earth is bathed in silver light; the air is warm, voluptuous, and redolent of innumerable sweet scents. Divine night! Magical night! Motionless, but inspired with divine breath, the forests stand, casting enormous shadows and wrapped in complete darkness. Calmly and placidly sleep the lakes surrounded by dark green thickets. The virginal groves of the hawthorns and cherry-trees stretch their roots timidly into the cool water; only now and then their leaves rustle unwillingly when that freebooter, the night wind, steals up to kiss them. The whole landscape is hushed in slumber; but there is a mysterious breath upon the heights. One falls into a weird and unearthly mood, and silvery apparitions rise from the depths. Divine night!”

(Translated by Claud Field)

So does Lermontov, in a poem dedicated to another Ukrainian native Maria Shcherbatova:

For society’s chains,

For the tiring glitter of balls

She gave up the blooming

Ukrainian plains

But there is still a trait

Of her native south

She’s kept in the blazing,

Cold, merciless light,

In how the words

Like Ukraine’s warm nights

With their non-fading stars,

Full of mystery fall

From her fragrant-lipped mouth.

Anton Chekhov writes in The Man in a Case: “The Little Russian [language] reminds one of the ancient Greek in its softness and agreeable resonance.” (Translated by Constance Garnett)

From The Life of Arseniev by Ivan Bunin: “That's Shevchenko, a truly brilliant poet! There is no country in the world more beautiful than Ukraine.” (Translated by Heidi Hillis, Susan McKean, and Sven A. Wolf)

Mayakovsky, Debt to Ukraine:

“I tell myself:

Comrade Moskal,

At Ukraine,

You don’t poke fun.

Learn

The mova

You see written in scarlet

On its lexicon banners,

For the mova is noble and simple.

(Translator's note: Moskal is a derogatory Ukrainian term for “Russian”. Mova is the Ukrainian for “language”.)

Dragging in a bunch of quotations from the “greatest hits” to back any conclusion on any hot topic is easy as pie. “Diagnosing” the culture of an entire nation based on a handful of quotes is a no-brainer. If one can at all judge the extent to which Russian literature is responsible for the war and Russia's war crimes, one should probably look into “Russian literature” as a school subject and not the phenomenon at large. Thus, apart from an insulting verse about Taras Shevchenko, Joseph Brodsky also wrote:

“... and when “the future” is uttered, swarms of mice

rush out of the Russian language and gnaw a piece

of ripened memory which is twice

as hole-ridden as real cheese.”

If one can at all judge the extent to which Russian literature is responsible for the war and Russia's war crimes, one should probably look into “Russian literature” as a school subject and not the phenomenon at large

The phrase “Russian literature” evokes the teacher's heavy steps from our collective memory. She enters the room, which smells of chalk and wet rags. Dusty portraits of grim-faced “great writers” stare at us from above the no-less-dusty cabinets. The teacher is holding a teaching guide, probably approved by Comrade Stalin himself. The guide clearly indicates which characters are “a ray of light” and which most certainly aren't. Which poets are advocates of freedom, and which are retrogrades and tyrants’ minions. Who wrote about the superfluous man, the little man, and the new man. The teacher walks up and down the aisles like a prison guard and dictates. Students take notes and learn them by heart. For the next class, they already know that Katerina from Ostrovsky's Thunderstorm is “a ray of light in the dark kingdom”. Why is this so? What does it even mean? Such questions are deeply inappropriate and counter-productive because they push one to the slippery path of introspection and doubt. The school course of literature teaches us to learn things by heart instead of analyzing or empathizing. Even worse, it encourages conformism in students and almost turns it into a reflex. First, you fill your essay with ideas from your textbook instead of your own. And then, before you know it, you “simply” follow your commander's orders.