The election results in the German federal states of Saxony and Thuringia have hit the federal government hard: not only did the ruling parties lose resoundingly, but the far-right Alternative for Germany won in Thuringia and came close to taking first place in Saxony. However, the results in these regions are more of an anomaly than a trend, and they are unlikely to be repeated in the whole of Germany when federal elections are held a year from now, argues political analyst Ivan Preobrazhenskiy. The probability of a change of power in Germany is indeed high. However, its beneficiaries will not be pro-Russian parties, but the old familiar bloc of the Christian Democratic Union and the Christian Social Union.

A challenged triumph in Thuringia

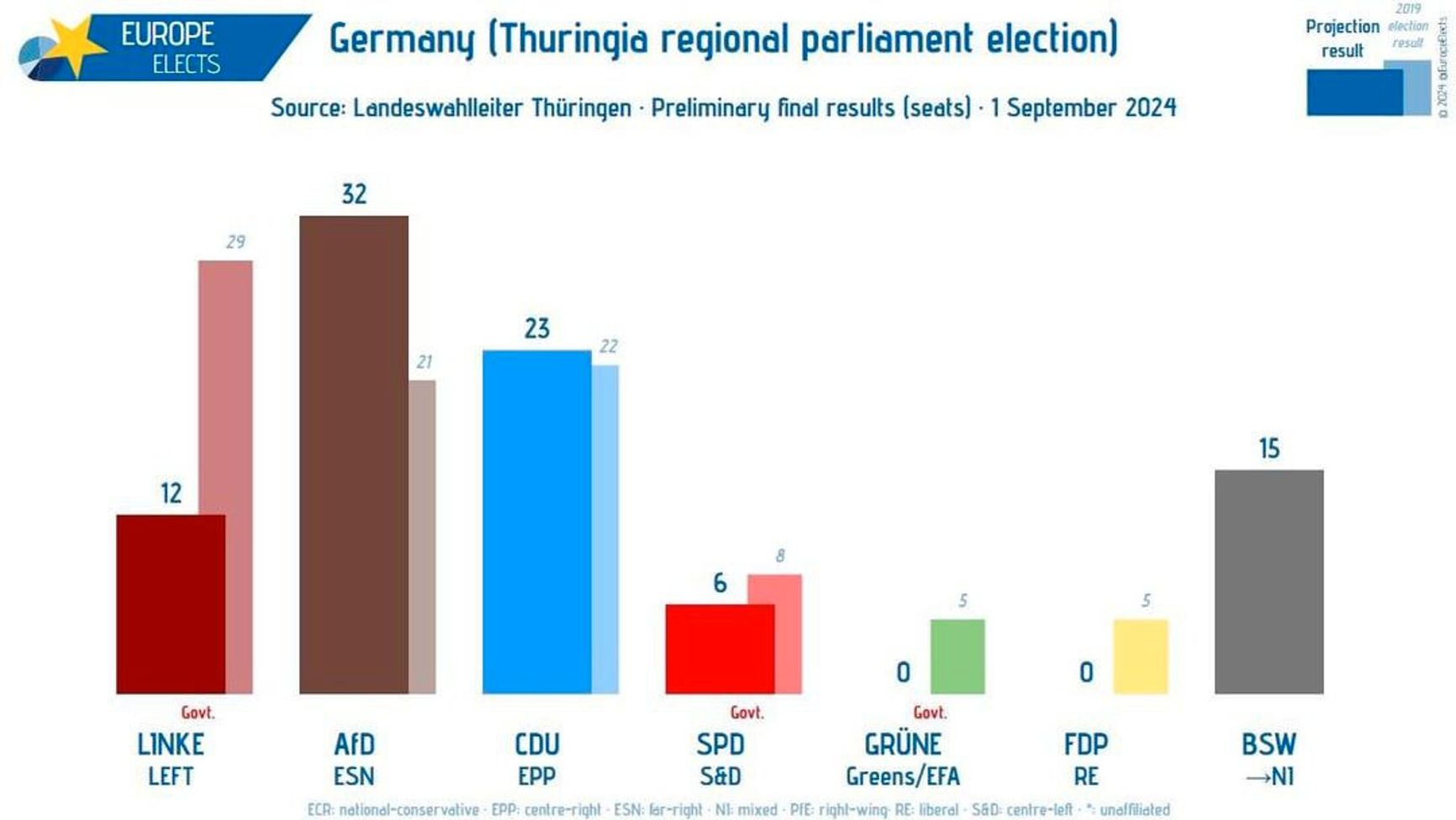

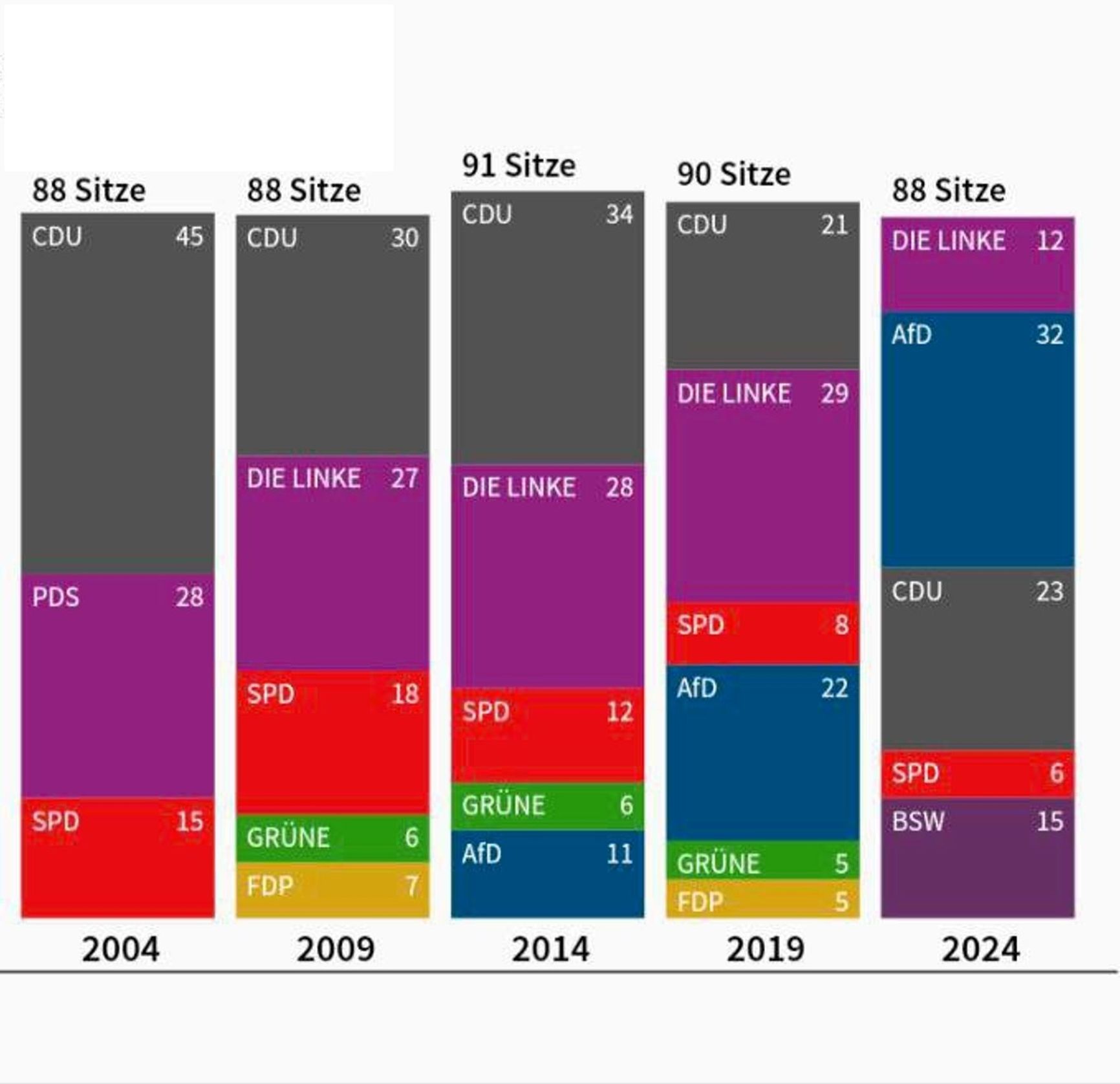

A small, economically depressed state with a population of 2 million people in the south of the former East Germany has drawn the attention of the whole country. The latest regional elections in Thuringia ended in a shock victory (32,8%) for the right-wing populist party Alternative for Germany (AfD), which advocates rekindling relations with Russia and canceling aid to Ukraine. The runner-up was the current leader of Germany’s “conventional” opposition — the right-wing Christian Democratic Union (CDU), with 23.6% of the votes. Third place was secured by a newcomer, the Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance – Reason and Justice (15.8%), a political force spawned by the pro-Russian wing of the Left Party.

Election results in Thuringia

One-third of the votes is a striking result for the AfD, whose local leader defiantly drove to the polls in a Russian-made Niva — once a popular make in rural areas. The right-wing populists are now demanding inclusion in the federal government and leadership in the state government. However, there are two obstacles to these plans.

The first obstacle is the declared reluctance of all the other parties to enter into a coalition with the AfD, even if it technically won the elections. A similar situation arose in neighboring Poland last year when the right-wing populist Law and Justice (PiS) party won a plurality in national elections, only for the country’s other political forces to unite in a parliamentary coalition that kept the “winner” out of government.

All other parties in Thuringia swear they will not enter into a coalition with the AfD

Despite rumors, the idea that the Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance might form an alliance with AfD, thereby allowing it to control a majority of seats in Thuringia’s state parliament, the Landtag, is nothing but a scare story. For the left-wing populists, forming such a coalition on the eve of the upcoming national elections in 2025 would be an act of political suicide. First, a significant portion of the votes for Wagenknecht come from Germans who share populist attitudes but are hesitant to support the extreme right. Second, the left-wing populists, who only registered in 2024, are steamrolling their way into national politics precisely because a significant segment of businesses that previously sponsored the AfD have grown tired of it and decided to foster an “alternative for the alternative.”

As support for the AfD grew, the CDU faction in the Thuringian parliament shrank

Parallels with the German domestic politics of a century ago, as far-fetched as they may seem, serve as an interesting analogy. Whereas early 20th century businesses donated to the National Socialists out of fear of the Communists, today the opposite is true: sponsors are flocking to the left-wing populists due to fears of the far-right. The same is true of Germany’s numerous Putinverstehers — the so-called “Putin understanders,” who advocate reaching a mutually acceptable bargain with the Kremlin. They appreciate Wagenknecht's calls for normalizing relations with Russia, ending military support for Ukraine, and resuming purchases of Russian oil and gas so that the party’s constituents can save money on heating.

A hundred years ago, German businesses gave money to the National Socialists — now, to left-populists

There are indeed similarities between the AfD and the Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance in foreign and even domestic policy. Both use populist slogans about “protecting ordinary citizens.” However, it is only by following the Thuringia tactic, moving as two columns — one on the left, and one on the right — that they can win the maximum number of votes. Attempting a systemic alliance that goes beyond situational considerations (such as the Ukraine issue) would only lead to the collapse of both parties. Even after the German federal elections next year, one can hardly imagine anything bigger than temporary alliances between the two parties on individual issues in the Bundestag.

Which brings us to the second obstacle: the willingness of the runner-up CDU, which took home 23.6% of the vote, to unite with the left as part of a grand coalition. The odds of the CDU allying its forces with the Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance and the Social Democratic Party (6.1% in Thuringia) are much higher than the possibility of any of these parties uniting with the politically undesirable AfD.

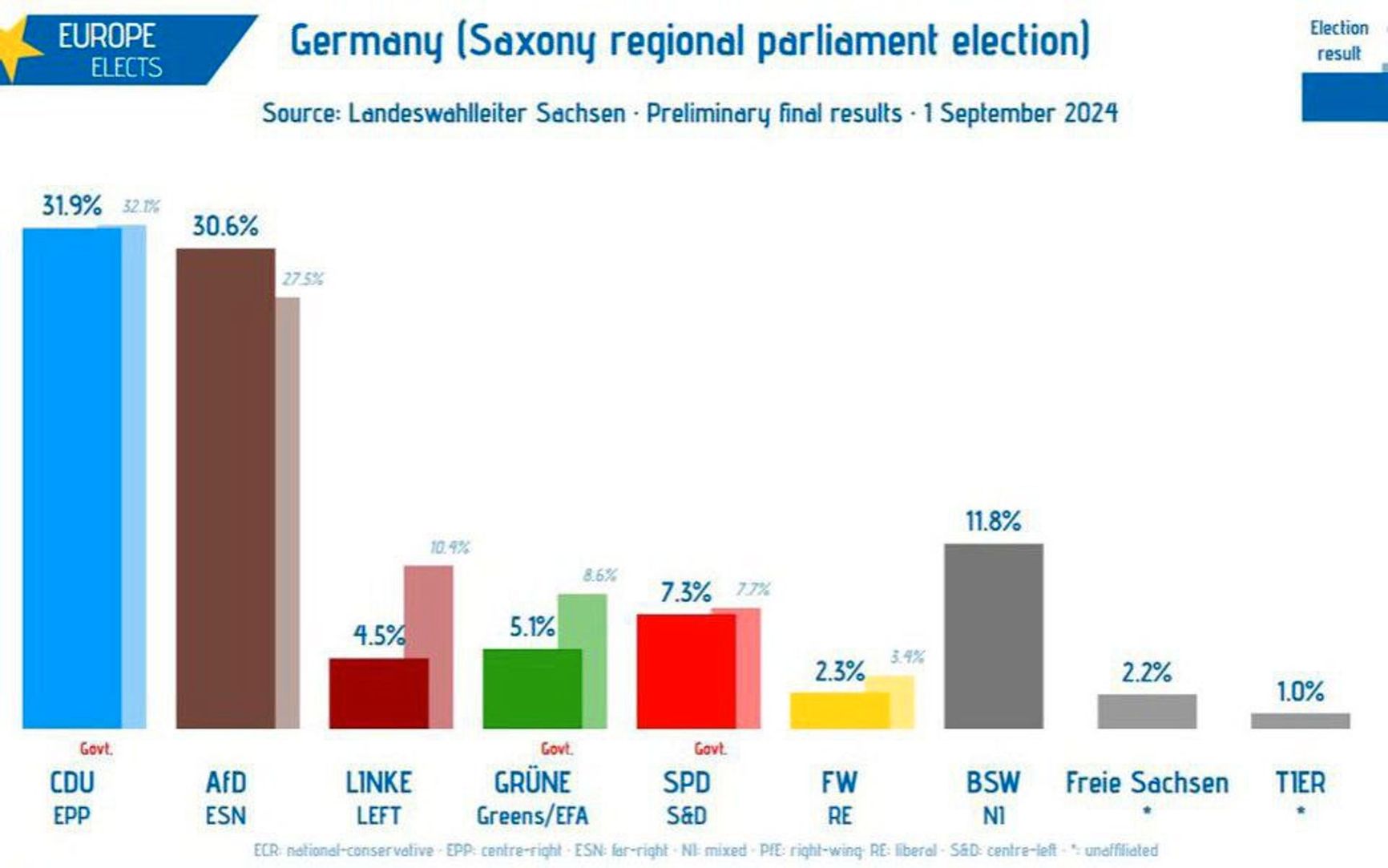

Saxony as a model for the German elections 2025

The elections in Saxony, which neighbors Thuringia, were even more scandalous, even if the Alternative for Germany finished a close second to the CDU. AfD’s defeat was predictable, as it was in line with polls conducted one month before the election. Incidentally, certain features of the Saxony campaign reminded Russian observers of the kind of politics practiced back in the bygone days when Russia maintained at least a semblance of free elections.

Election results in Saxony

First, even after coming in second (30.6% versus 31.9% for the CDU), the AfD found itself without a blocking minority in Saxony’s state parliament. The early election results suggested that the AfD could hope for a “golden share” on decisions such as calling early elections, changing the Basic Law of the state, appointing “constitutional” judges, and generally stalling any coalition formed without its participation. All of the above requires 41 mandates, which the AfD thought it already had in its pocket.

However, to the outrage of the far-right, which already doubted the objectivity of the vote count, it was announced that a technical error had occurred. As a result of the correction that followed, the Greens and the SPD gained one additional mandate each, while the AfD and the CDU lost one mandate each. In other words, the adjustments affected Christian Democrats as well, thus confirming the objectivity of the decision to outside observers — but not to the AfD right-populists, who treat all other parties as a single hostile force.

Another similarity to the Russian elections that might have caught the eye of political analysts was the emergence of a spoiler party. Notably, this tactic came into use some time ago in Bavaria, where in 2023 the local Free Voters party, the AfD's fellow right-wingers, won 15.8% before entering into a coalition with the CSU (the CDU's Bavarian partner), forming a joint center-right government that left the AfD out of the picture.

In Saxony, the Freie Sachsen (“Free Saxons”) played a similar, albeit more modest role, receiving 2.2% of the vote — slightly more than the margin that separated the AfD from the first-place CDU. Just in case it needs to be stated, this outcome was not the result of a conspiracy: competitor far-right parties form not as the result of someone's cunning plan, but because the AfD’s scandalous, pro-Russian policy scares away even ideologically similar right-wing extremists, who register their own parties, thereby taking votes away from the AfD.

A spoiler party of sorts, the Free Saxons, received 2.2% of the vote, snatching the margin that could have brought victory to the AfD

The campaign in Saxony looks like a model for the national elections of 2025. The parties of the current ruling coalition — Chancellor Olaf Scholz's SPD, the Greens, and the Free Democrats — failed at the polls (and in Thuringia, the latter two did not even cross the 5% threshold necessary for getting into the Landtag). First place in Saxony, as in the opinion polls, went to the CDU, and their results will be much higher in more prosperous western Germany. The “success” of the AfD, whose results are likely to hover at or above 20% nationwide, was not sufficient to bring it into a governing coalition. Finally, the triumph of the young Sahra Wagenknecht's Alliance is evident: despite failing to exceed the 15% threshold, as it did in Thuringia, it can compete in popularity with the current ruling Social Democrats.

Meanwhile, the election in Thuringia, as big a splash as it made, will not become a blueprint for all of Germany. Rather, it was an anomaly, which only confirms that right-wing populists can count on resounding success solely in disadvantaged regions. At least for now, the further west one goes, the more centrist Germans become.