Using convicts in wars over new territories is a long-standing Russian tradition. However, the results have always been anything but positive. Exiles and hard-labor convicts bore the brunt of the military effort in the defense of Sakhalin during the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905), which the Russian government expected to be «little and victorious» but went down in history as one of Russia’s most humiliating defeats.

On the morning of June 24, 1905, a Japanese squadron of 53 ships approached the rocky, heavily forested coast of Aniva on the southern side of Sakhalin and began the beaching of the 14,000-strong landing force of the 15th Division. The Russian defense force on the island was limited to 1,500 troops and four militia groups, consisting mainly of exiled settlers and hard-labor convicts. The only distinction of the militiamen from civilians was a tin-cut militia cross on the crown of their peakless caps.

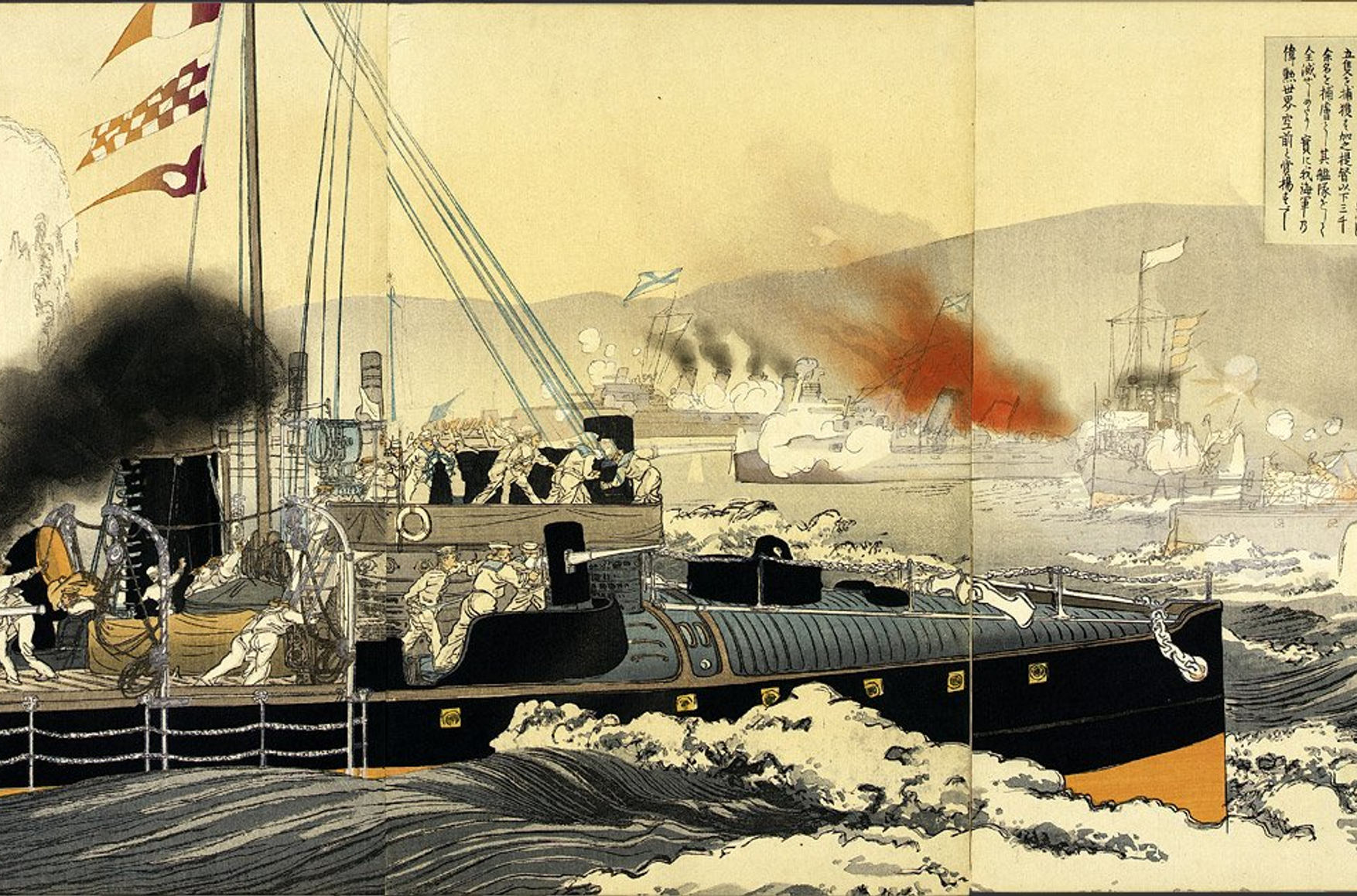

This attack opened the final stage of the Russo-Japanese War. Long gone was the enthusiasm that had swept the nation in the first weeks of the “little victorious war”, as Russian Minister of the Interior Vyacheslav von Plehve had prematurely dubbed it. In February and March 1904, shop windows were teeming with cheap woodcut prints depicting the Japanese as macaques, or at least as frightened cripples, whom valorous, enormous Cossacks were beating with nagaikas. Large cities of the Russian Empire saw massive pro-war rallies (even though some of their leaders were later identified as undercover policemen). The patriotically-minded audience demanded that «God Save the Tsar» be sung three or four times during any theatrical performance. In those early weeks of the war, even newborn boys were often named Bronenosets – the Russian for “battleship”.

Long gone was the enthusiasm that had swept the nation in the first weeks of the “little victorious war”

As the months passed, one defeat followed another, making it increasingly clear that this war, “incomprehensible in its pointlessness”, in the words of the writer and military doctor Vikenty Veresaev, would result in a serious disaster for Russia. The command of the sea, which Nicholas II considered the most important objective, quickly came to naught. A surprise attack of the Japanese fleet on the Russian squadron on the night of January 27, 1904, disabled several of the strongest ships, the pride of the Russian fleet: the Tsesarevich, the Retvizan, and the Pallada. The Japanese landed in Korea. In May, while the Russian command was inactive, they landed on the Kwantung Peninsula, to cut off communication between Port Arthur and Russia. The garrison of Port Arthur surrendered in December 1904 after several months of siege. The remnants of the Russian squadron at Port Arthur were sunk by the Japanese or blown up by its crews.

This war, “incomprehensible in its pointlessness”, would result in a serious disaster for Russia

In February 1905, the Japanese forced the Russians to retreat in the decisive Battle of Mukden. When the Japanese defeated the Russian squadron redeployed from the Baltic in the Battle of Tsushima on May 15, 1905, the outcome of the war was set in stone.

Popular discontent was growing and would culminate in a revolution before long. After the battles in Manchuria – “a bloody fog ... of corpses, corpses, corpses”, as Veresaev put it – a hurricane of mobilization swept through the country to make up for the losses. Just when peasants were bemoaning soaring prices and increased taxes, the ruthless mobilization machine reached them as well, “instantaneously snatching them away from their affairs at full throttle, without letting anyone close or finish their business”.

Just when peasants were bemoaning soaring prices and increased taxes, the ruthless mobilization machine reached them as well

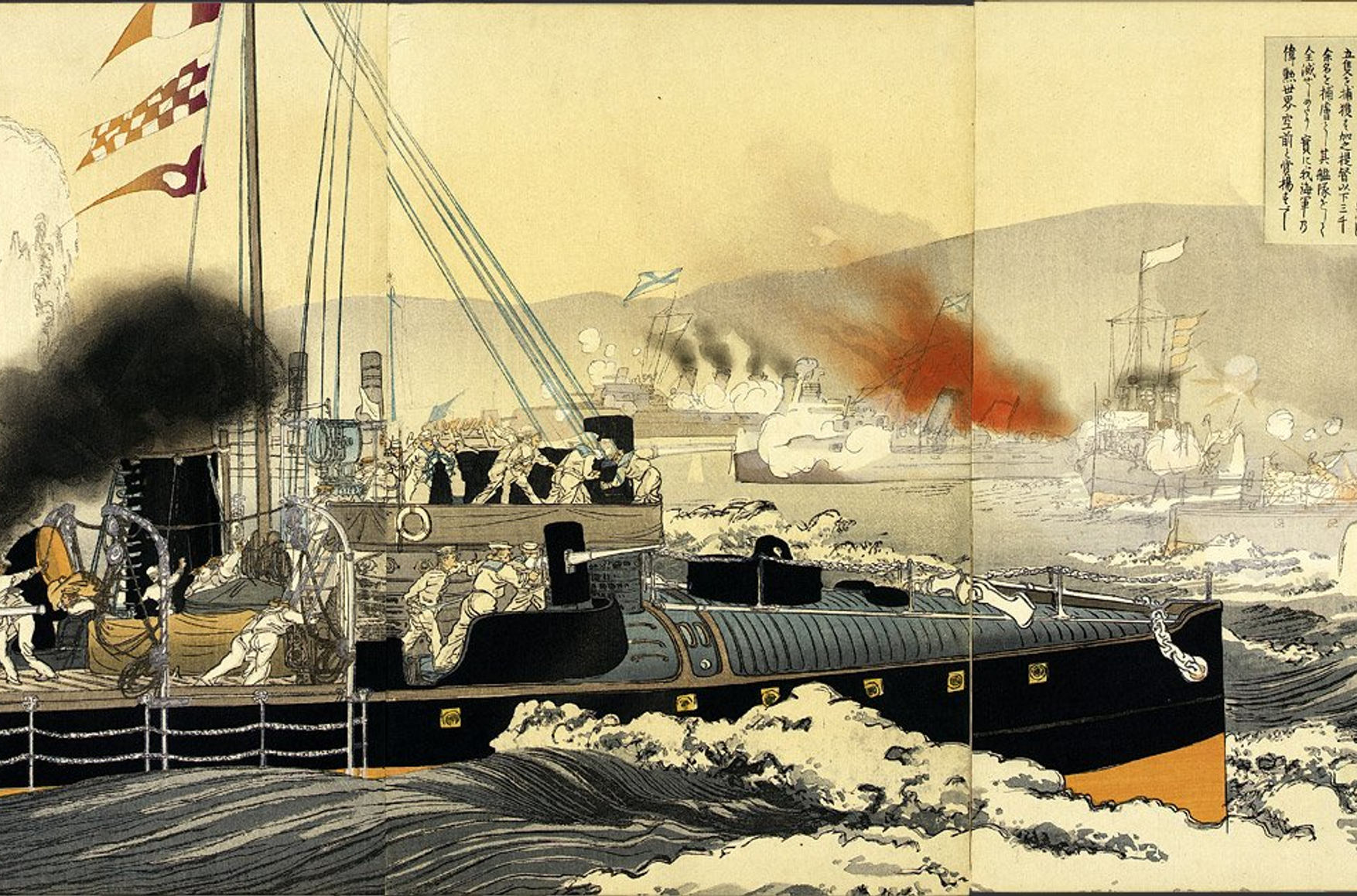

After the brutal defeat of Admiral Rozhdestvensky's Baltic Squadron in the Battle of Tsushima, the last thing Japan had to achieve was to gain control of Sakhalin. Among other things, it would allow the Japanese to sign a peace treaty on more favorable terms.

The battleship Oryol after the Battle of Tsushima

“No one has any use for or any interest in Sakhalin,” remarked Anton Chekhov's friend and publisher Alexey Suvorin when Chekhov announced to him his plans to visit the “hard-labor island”. Russia did not plan on setting up a serious defense for an extremely remote island, sparsely populated, with harsh nature and virtually no communications. Intelligence reports on Japanese plans to attack Sakhalin did not receive much attention.

The Russians expected to fend off such attacks, if any, with 1,500 troops and six cannons. The plan also included creating a 3,000-strong militia force from among local hunters, exiled settlers, and even convicts. Yevgeni Alekseyev, the viceroy of the Russian Far East, issued an order to that effect at the very beginning of the war. The government promised food allowances and a reduction in the period of exile and imprisonment. These terms attracted many settlers and prisoners to the militia.

The government promised food allowances and a reduction in the period of exile and imprisonment

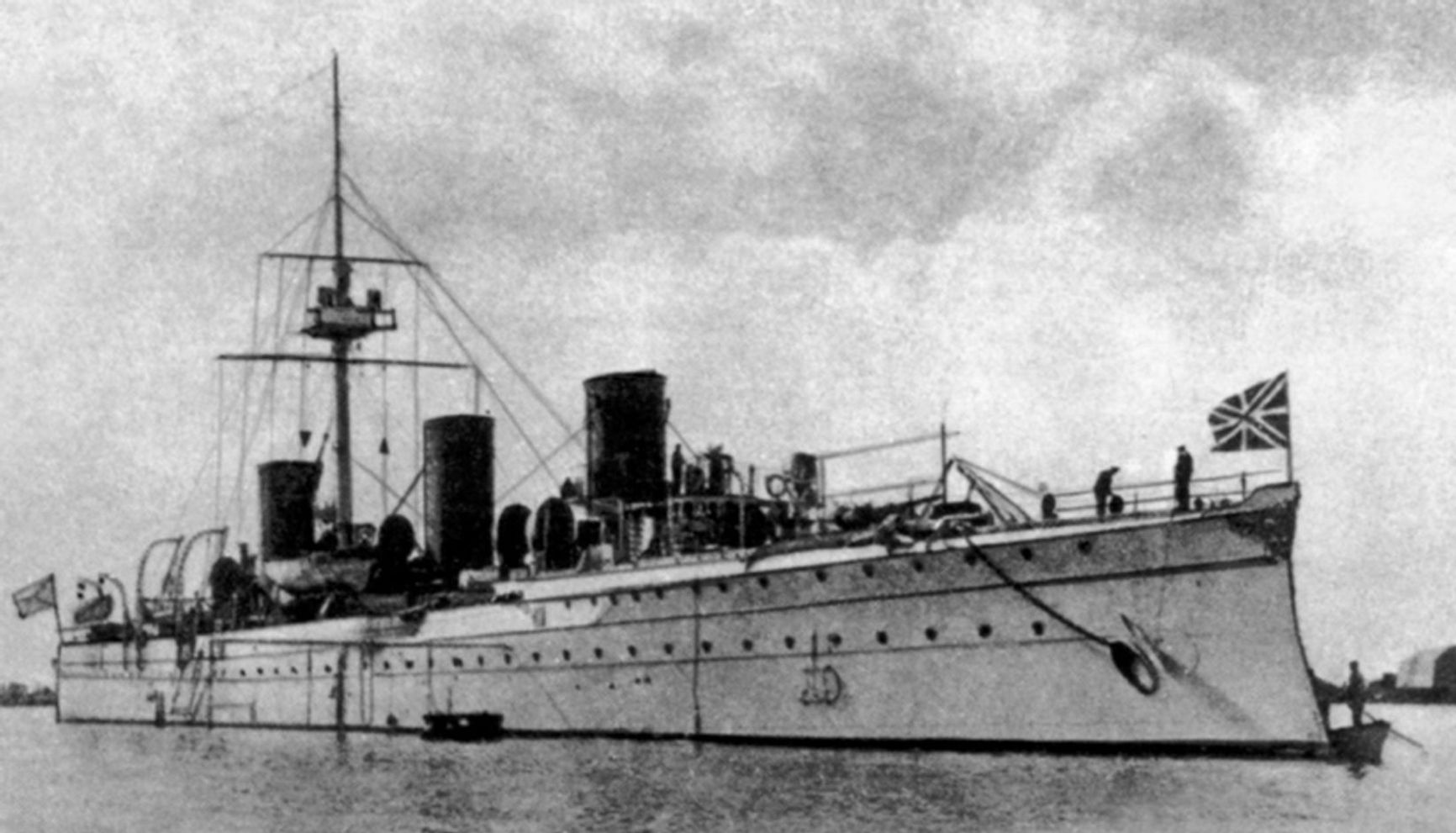

The militiamen were armed with Berdan rifles, or simply berdankas, each with 340 rounds of ammunition. They did not get any uniforms, though. The only detail that distinguished the militia from the civilian population was the so-called “militia cross” on their peakless caps. And they were a far cry from the beautiful brass crosses, which were introduced for the militia in 1812. The crosses for the Sakhalin militia were crudely cut out of tin during the hurried preparation for the defense.

Considering who these people were and how they lived, it becomes clear that they could hardly be expected to show self-sacrifice in serving their tsar. Most of them were murderers sentenced to hard labor for life. The first group of local convicts was selected for participation in an “Australian model” experiment, which the authorities hoped would help reduce crime that had soared after the abolition of serfdom, and had to cross the entire Siberia on foot to reach Nikolayevsk, which took up to 14 months. Subsequent groups of a thousand convicts a year were brought to Sakhalin by sea, and they spent two to three months in the holds, shackled.

Sakhalin hard-labor convicts

For the first three to five years on Sakhalin, they worked mostly in the coal mines, shackled with hand and foot shackles and sometimes chained to wheelbarrows. They lived in earthen-floor barracks holding 30-50 people each. Those who committed new crimes in custody were executed by an executioner – also from among the convicts. Those who had served their sentences became exiles. They were given a plot of land in the middle of the taiga, and with a government-issued axe, shovel, hoe, two pounds of rope, and a month's supply of provisions, the settlers set out to cultivate their plot of land and build themselves a house. Since there were ten times as many men as women coming to Sakhalin as convicts, when the women were released for settlement, they had to marry male exiles who had distinguished themselves by their exemplary conduct. Exemplary conduct could also earn you assistance with setting up a farm: such exiles were given a cow and seeds at the public expense.

However, farming was tough in this harsh land, and the island's natural riches were not generating income due to technological backwardness, a shortage of workforce, and corrupt officials. Although the exiles were expected to remain on the island forever and steadily increase its population, they fled the island at the first opportunity.

One could hardly count on the loyalty of such a militia contingent. Their military training was entrusted to the chiefs of the prison department, as the officers for the new militia detachments did not arrive on Sakhalin until April 1905. Of the 2,400 exiles and convicts who initially enlisted in the militia, more than half had simply dispersed by the beginning of hostilities. With such a force, defending the island was impossible. It is commonly believed that the military and administration were not evacuated from Sakhalin only because they were afraid to show weakness.

Russia’s only hope was to count on the remaining troops to join the militia in guerrilla activity, although no concrete plans had been drawn up to that effect.

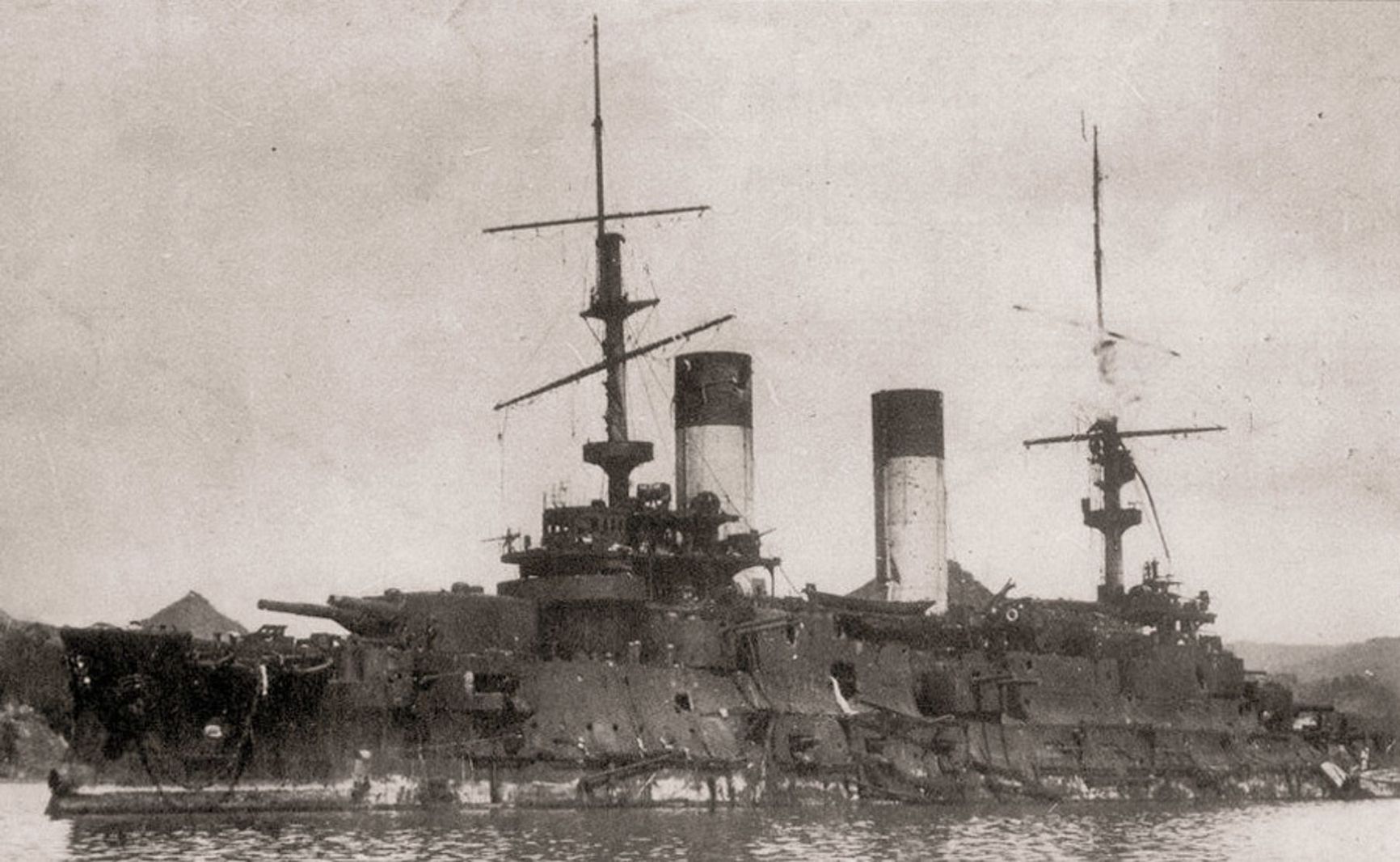

The command assigned areas of operation for each of the five 200-strong guerrilla detachments, which also included sailors from the sunken battleship Novik, and set up warehouses for them in the taiga. After a brief resistance to the vastly superior Japanese landing force, the Russian detachments retreated into the taiga.

The Novik cruiser

Sakhalin's military governor Mikhail Lyapunov (a prison lawyer, far removed from military affairs) and his subordinate troops surrendered on July 19. The core of the island's defense, led by Colonel Artsishevsky, was also encircled. Some of them were slaughtered, and some surrendered. Learning of their fate, Captain Dairsky's detachment, which tried to break through to them, changed plans and for a while continued to operate independently in the valley of the Susui and Naiba rivers, but also sustained defeat. Arkhip Makenkov, a machinist from the Novik who witnessed the detachment’s death, recounted their fate. According to Makenkov's report, Dairsky was captured along with the wounded he refused to leave, and the rest of his men were lured out of the forest by the Japanese, who had forced the wounded to shout “Russians, come out, we won’t harm you!” Makenkov and one of the convict militiamen did not surrender and secretly followed the detachment for 12 versts to the place of its execution, which Makenkov described in his report.

Makenkov himself is considered the last defender of Sakhalin. After the execution of Dairsky’s detachment, he went looking for another detachment to join but found no one. Makenkov wrote:

«How long I walked without food, I don't remember. I bypassed villages. Outside Leonidovo, I came across a tent with two Japanese sappers and an engineer officer. When they fell asleep, I stabbed them to death. I took a cotton blanket, compass, map, matches, canned food, an Arisaka rifle, a handgun, and binoculars...”

Makenkov entered the northern part of Sakhalin, which remained under Russian control, on October 20, 1905.

Only one militia detachment, led by Captain Bykov, correctly assessed the situation and made the right decision. Learning that the main force and the governor of the island had surrendered, Bykov decided to take his unit to the mainland. They captured eight Japanese-type kungas fishing boats and attempted to moor to the mainland but failed due to the storm. Forced to return to the shore of Sakhalin, they found a guide who took them through the taiga to Cape Pogibi in seven days. There, Bykov hired a Gilyak (a representative of an indigenous Far Eastern people), whom he sent to the mainland across the Tatar Strait with several militiamen. A vessel arrived from Nikolayevsk a few days later and evacuated the 203 people who had joined Bykov by then. These soldiers, sailors, and militiamen walked a total of about 900 kilometers through the taiga.

On August 23, 1905, the Treaty of Portsmouth was signed, and South Sakhalin became Japanese until 1951. Modern-day amateur archaeologists sometimes come across tin militia crosses in the taiga, in the locations of battles or executions, along with shell casings, remnants of equipment, and bones, and sell them to collectors via various specialized websites, where militia crosses from Sakhalin value much higher than their earlier brass counterparts due to their rarity.