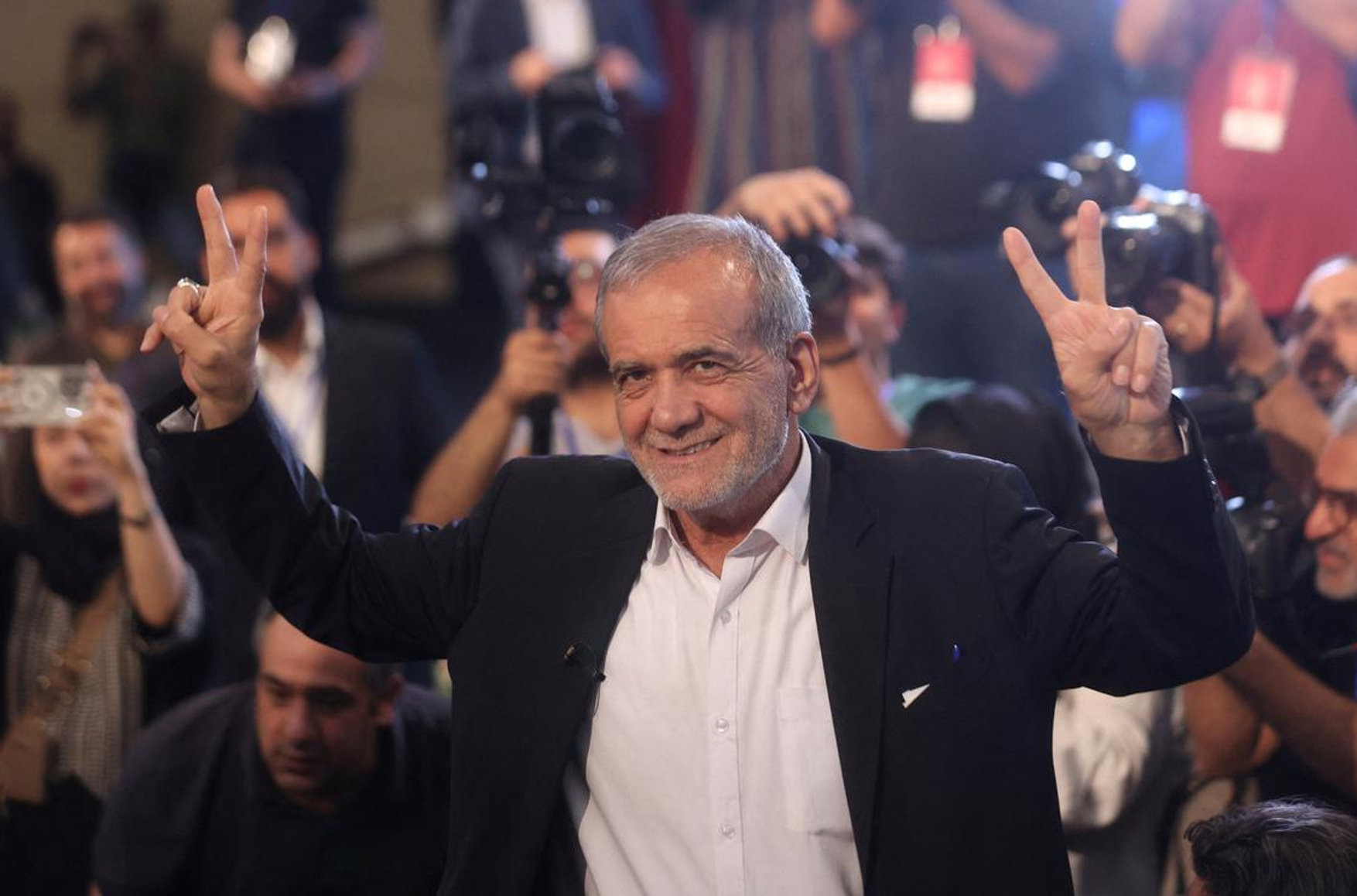

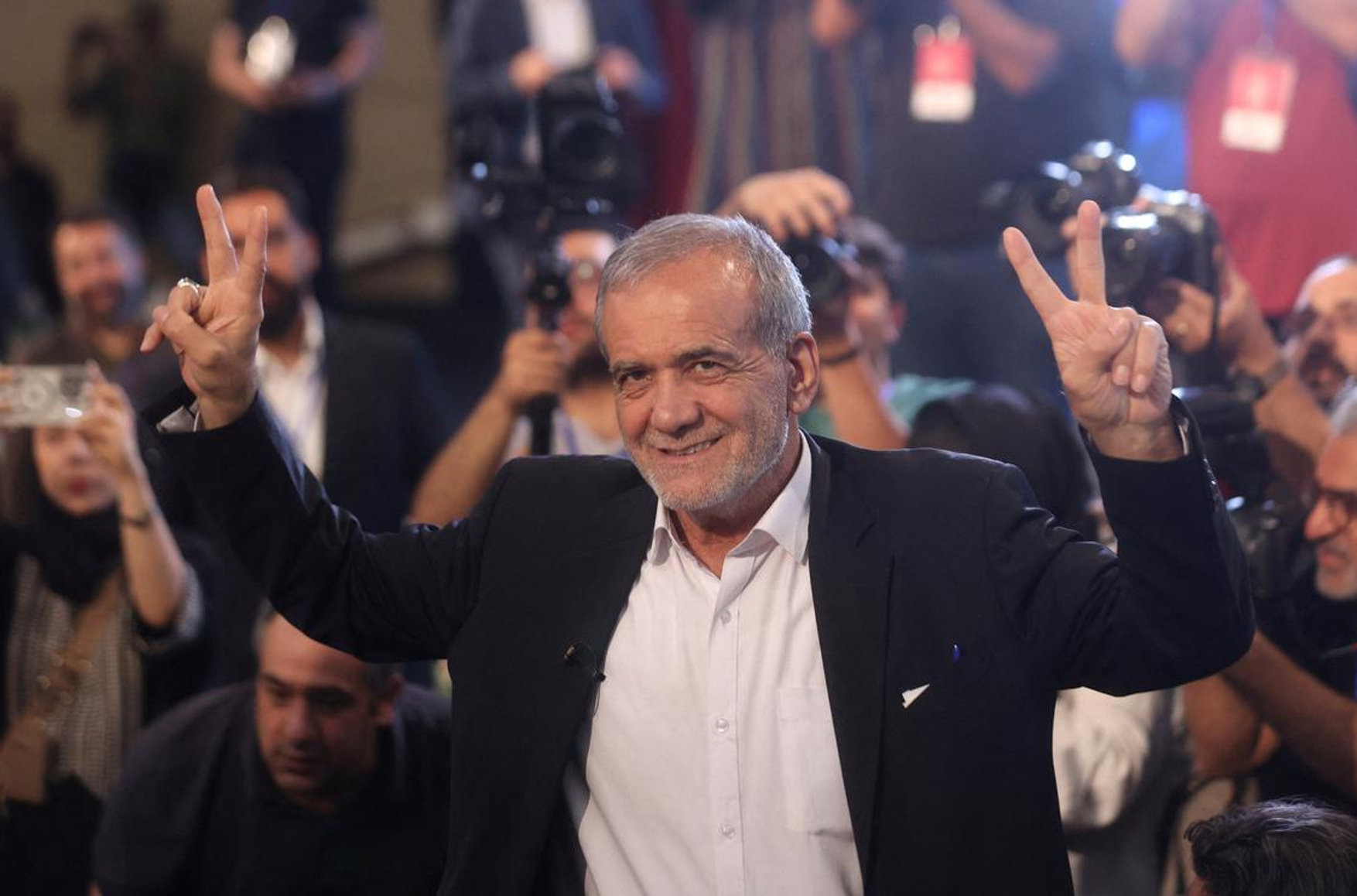

The unexpected victory of a reformist candidate in Iran's presidential election has seemingly revitalized the country's stagnant political process. Although he is not the kind of politician who publicly pushes for relaxation of the hijab law or a rollback of Internet restrictions, Masoud Pezeshkian nevertheless became a protest candidate — albeit one who demonstrates that he is well aware of the red lines delineated by Iran's Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Khamenei. Iran scholar Nikita Smagin argues that, despite the record-low voter turnout, Iranian society is permeated by a single major demand: a thirst for change.

An extraordinary election

The fact that the election took place is already an extraordinary event. Early in 2024, Iran's post of president was held by Ebrahim Raisi, a conservative and consistent traditionalist who enjoyed support from both spiritual leader Ali Khamenei and most of the conservative wing’s forces. By the early 2020s, Iranian conservatives had finally driven the much-detested reformers out of the political field, completely monopolizing the levers of power in the process. Iran’s 2020 parliamentary elections and 2021 presidential vote followed a similar pattern: no significant alternative forces passed through the electoral filter, and as a result, the conservatives won despite plummeting turnout.

After three decades of intense political struggle between reformers and conservatives, the system appeared to have lurched to the right, where it was expected to remain until Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, who is currently 85 years old, ultimately left the stage.

After three decades of intense political struggle between reformers and conservatives, the system appeared to have lurched to the right

The parliamentary elections in early 2024 only reinforced this trend, with almost all alternative candidates being squeezed out of the process. These elections delivered the highest-ever share of elected conservatives (233 out of 290 seats) on the lowest turnout in history (about 40%).

Then an unexpected accident created room for change. On May 19, 2024, President Raisi met his sudden demise in a helicopter crash. Following the prescribed procedure, Iranian authorities announced early elections.

Ebrahim Raisi's helicopter crash site

Few candidates applied, at least by Iranian standards: a mere 80 aspirants for office. Unsurprisingly, Iran's Constitutional Council kept unpredictable former president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad (2005-2013) out of the race, along with well-respected moderate Ali Larijani, who for many years was speaker of the country's parliament.

The list of pre-approved nominees brought no surprises: five Conservative candidates, three of whom looked like obvious spoilers, and a reformist contender whose only purpose was to create the illusion of competition.

Current speaker of parliament Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf, a pragmatic conservative close to the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC), appeared to be the frontrunner. A seasoned politician, Ghalibaf has shown himself to be a loyal and manageable player. In the previous elections, he obediently withdrew his candidacy in favor of Raisi, possibly getting the post of parliamentary speaker as a concession.

Conservative Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf was considered the most likely candidate for Iran's presidency

In addition, Ghalibaf had a small but stable pre-existing electorate — something other contenders lacked. His main rival was Saeed Jalili, whose main asset was his proximity to Khamenei in his capacity as the Iranian leader's representative on the Supreme National Security Council.

Hardliner Saeed Jalili's main asset was his proximity to Khamenei

Meanwhile, Pezeshkian appeared to be nothing more than a token candidate, a name on the ballot almost unknown to ordinary Iranians. Pezeshkian’s only notable political achievement dated back to the 1990s, when he served as health minister in the government of Mohammad Khatami, the most memorable reformist president in Iran's history. However, the 2024 election played out quite differently from the projected scenario.

Few believed in Pezeshkian's victory

A sensational result

The election race offered little excitement. Candidates argued different points of view, but the debate was not exactly fierce. Notably, five candidates out of six (everyone but Jalili) criticized the country’s Guidance Patrol — a literal morality police squad tasked with enforcing adherence to Islamic law — for excessive brutality in enforcing the requirement that women properly wear the hijab when out in public. But everyone, Pezeshkian included, proceeded with extreme caution: no promises were made to remove these patrols from the streets or to revise the Islamic dress code. All the candidates did was to suggest that more moderate methods of enforcement be used.

Nevertheless, pre-election polls already placed Jalili and Pezeshkian slightly ahead of the others. And the numbers were not wrong: the first round ended with a sensational outcome, a second-round runoff for only the second time in Iran's history (the first was in 2005). Pezeshkian got 10.4 million votes against Jalili's 9.4 million, while the projected front-runner, Ghalibaf, was excluded after coming in third with just under 3.4 million. As a result, the second round was a standoff between polar opposites: Pezeshkian, the only reformer on the list, and Jalili, the ultimate hardliner.

The second round was a standoff between two polar opposites: Pezeshkian, the only reformer on the list, and Jalili, the ultimate hardliner

Pezeshkian advocated for restoring the nuclear deal — the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action signed in 2015 by Barack Obama before being abandoned in 2017 by Donald Trump — to bring Iran out of international isolation and solve its financial problems. He also promised to launch cultural and economic reforms. Meanwhile, Jalili argued that the U.S. should be held responsible for ruining the nuclear deal and consistently supported the mandatory wearing of the hijab, saying that it “preserves the sanctity of the institution of the family.”

What happened next was even more bizarre. Supporters of Ghalibaf, the losing conservative, called on one another to vote for the reformist Pezeshkian in the second round. Either they were resentful of Jalili because the parties had failed to agree on a single conservative candidate, or some deeper internal power struggle was taking place.

Supporters of Ghalibaf, the losing conservative, called on one another to vote for the reformist Pezeshkian in the second round

Discord among conservative forces

The rift between supporters of Jalili and Ghalibaf highlighted an issue that seemed unimportant before the election but became a key to Pezeshkian's victory: a rift among Iranian conservatives.

Young politicians in Iran tend to believe their older colleagues are moving away from the ideals of the Islamic Revolution. As long as Raisi — a consensus figure — was president, the tension was moderate, even though the latest parliamentary election featured as many as five main lists of conservative candidates. (In Iranian political tradition, a candidate can be present on multiple electoral lists and coalitions.)

The protest vote served as another unexpected factor. The turnout at Iranian elections has been slumping year-by-year as disgruntled voters mostly choose to stay home on election days, meaning that those who do cast their ballots — often because they are public servants or members of the military — are largely loyal supporters of the authorities.

In the 2021 elections, opposition voters spoiled their ballots (almost 15% of votes, which was the second-best result). This time, however, they decided to express their protest in a different way: by voting for a reformer.

Victory amidst apathy

The first round ended with a historically low turnout figure: 40%, making it the fourth consecutive election in which turnout fell. Pezeshkian’s success in making it to the runoff boosted turnout for the second round — but still only to 49%, which is still very low by modern Iranian standards. The elections confirmed Iran’s predominant recent trend — and onslaught of political apathy caused by the nation's disillusionment with the Islamic Republic.

In the second round, Pezeshkian gained 16.384 million votes — the lowest number of votes accumulated by a winning Iranian presidential candidate since 1993. Consequently, it would be a stretch to say that the new president truly represents the expression of the Iranian people’s aspirations. The electoral sensation took place against the background of prevailing political apathy, only slightly stirred up by the unpredictable first-round result and fierce competition in the second round.

In the second round, Pezeshkian gained 16.384 million votes — the least impressive win in an Iranian presidential election since 1993

Pezeshkian is hardly a candidate of hope, considering that he only won the votes of a fraction of the population — and most of them supported him out of protest rather than genuine enthusiasm. For his presence to breathe new life into Iran’s currently lifeless political landscape, Pezeshkian must take decisive action on crucial issues, such as the hijab and internet censorship. However, nothing in his campaign suggested that he was willing to reset the political vector of the Islamic Republic. On the contrary, Pezeshkian's rhetoric reveals a cautious mainstream politician who is well aware of the red lines drawn by the Supreme Leader.

Many conservatives, which includes Ayatollah Khamenei’s entourage, appeared to be content with Pezeshkian's election. After the 2022 protests signaled a crisis of legitimacy in the country, many in power considered bringing reformers back to the playing field, hoping to reinvigorate mass participation in the political process.

Moreover, a mainstream, moderate reformist president is unlikely to seriously challenge the Supreme Leader or the course he has set for the nation. After all, reformers have held the Iranian presidency most of the time since 1989. The only exceptions were Ahmadinejad and Raisi, who were in office for a combined 11 years, while the reformist wing held the office for the remaining 24 years. In other words, the combination of a reformist president and a permanent, conservative spiritual leader is a customary arrangement for Iran's political system.

The combination of a reformist president and a permanent, conservative spiritual leader is a customary arrangement for Iran's political system

Of course, even a mediocre reformer as president offers a stark contrast to the strong conservative image that Raisi projected. However, going beyond cosmetic adjustments of foreign and domestic policies would require no small amount of determination and resilience from Pezeshkian. The last reformer in office, Hassan Rouhani, who held the presidency from 2013 to 2021, was not up to this challenge, despite initial successes with the nuclear deal. By the end of his second term, Rouhani had become a well-reputed expert who actively criticized Iran's current course but had his hands tied with his fear of crossing the spiritual leader.

While it remains to be seen how Pezeshkian’s presidency will play out, Iran’s political system has shown a capacity for unpredictable, truly competitive elections. This year’s unexpected vote has vividly demonstrated that Iranian society is permeated by one major demand: a thirst for change. And these sentiments may put pressure on the authorities, forcing them to react — and even to make concessions.