In the month after the June 23 terror attacks in Derbent and Makhachkala, Russia’s Dagestan region outlawed wearing the niqab in public, Sergokala District head Magomed Omarov was expelled from the United Russia party and taken into police custody, and head of Dagestan Sergey Melikov said that the republic was proud of its residents who perished at the hands of the terrorists. However, the authorities did not even attempt to explain the root cause of the tragedy. Over the past decade, regional leaders and the Kremlin itself became so confident in their triumph over the underground that they slept through the emergence of a next generation of “forest people,” says Vadim Dubnov. The new insurgents are much less involved in prosecuting clan rivalry or establishing ties with law enforcement and are a lot more religious, professing a branch of radical Islam brought from the Middle East — with support from local preachers. As the experience of waging war against ISIS has shown, fighting fanatics who are prepared to go to any lengths is no easy task.

Homemade terrorists

After the attacks of June 23, the head of Dagestan predictably spoke about the “foreign traces” of terrorism, uttering two key words: “Sleeper cell.” Dagestan has not heard anything like that in ten years — and neither has it used the word “forest” as a synonym for “armed underground.” The decade of calm reigned for a few reasons, but mainly thanks to the fact that armed resistance in Chechnya had dried up. Although each North Caucasian republic had its own agenda, Chechnya was the hearth of the region's underground. Its fighters had gained combat experience in the Chechen wars of the 1990s, similar to the way Albanian fighters from Macedonia and Serbia's Presevo Valley fought in Kosovo and turned their attention to local issues when they came back.

Meanwhile, Dagestan itself became the center of new Islamic trends in the region — primarily Wahhabism. Whereas religious radicalism failed to gain traction even in war-torn Chechnya, in Dagestan, it attracted only die-hard believers and the least scrupulous Muslims. However meager, this following has allowed the ideology to take root and grow.

Still, it is hard to connect the attacks in Derbent with last October’s seizure of the airport in nearby Makhachkala — these events are different in both nature and motivation. The search for Jews at the airport was a form of protest that got out of hand. The attackers emphasized, albeit unconvincingly, the fundamental difference between local mountain Jews and the rest of the “Yahuds,” who the pogromists considered responsible for the war in Gaza.

Those who attacked the synagogue in June, however, did not make such a distinction. In their eyes, the curse lies on all Jews, the first time such a formulation was stated with such clarity in the Russian terrorist discourse. This is why hypotheses about ISIS involvement arose so readily, while the suggestion by a Russian lawmaker that Ukraine was behind the attack failed to gain traction. Besides, the authorities are so reluctant to get to the bottom of the issue that their lack of action appears deliberate — as though they were not faced with a political threat.

In the eyes of the synagogue attackers, the curse lies on all Jews without exception — a new formula for terrorists inside Russia

After failing to thwart a second ISIS-style attack — the first being the Crocus City Hall concert massacre back in March — the authorities were probably concerned that excessive hype could result in the emergence of a second front in the Kremlin’s standoff with the wider world. At the same time, ISIS has somewhat lost its image as the hotbed of global terrorism and instead resembles a “franchise” that unites various autonomous groups. Nevertheless, ISIS-K — Islamic State - Khorasan Province — took responsibility for the Crocus City Hall attack. As for the events on June 23, however, no one has so much as staked a claim.

Most importantly, despite all assurances that the armed underground in Dagestan is a thing of the past, there are those in the republic capable of reviving it.

The many ways to “the forest”

Many linked the emergence of the old underground (commonly known as “the forest”) with the clan-based, corrupt hierarchy of Dagestani society. Even if it did not exactly squeeze out opposition-minded members into the underground, it certainly made the recruitment of new fighters easier. “The forest” may have been a form of political opposition at first, but this simplistic view is just a trait of the misguided optimism some shared back in the day — if we just take care of corruption, “the forest” will disappear.

However, the underground took on a life of its own, becoming both an enemy of the state and an extension of it. Adilgirey Magomedtagirov, a convinced fighter against the underground and Dagestan’s Minister of Internal Affairs, was shot dead in Makhachkala in 2009, in the middle of his daughter's wedding. The police blamed the underground, of course, but without too much fervor, adding off the record that the victim had controlled the section of the Baku-Novorossiysk oil pipeline running from Makhachkala to the border with Azerbaijan — along with all the illegal tie-ins and oil refineries, including the relevant customs offices. The investigative theory that “the forest” was involved in these schemes as a stakeholder or security provider was certainly valid at the time.

The underground took on a life of its own, becoming both an enemy of the state and an extension of it

There have been other notable incidents. A young man who was pressured by the police to incriminate himself decided to join the resistance. His father went to the police, and they set up a meeting with the underground warlord, who sent the son back home. A few months later, a car with the would-be insurgent's former comrades drove up to his house and took him away. At the nearest intersection, the car was shot up by the police.

“Militants photograph everyone who decides to join ‘the forest’ and send these photos to the police — to make sure the recruits cannot go back,” a knowledgeable source explained to me years ago. I was taken aback — but no one in Dagestan would have batted an eye. “Militants turn in anyone who walks away from them. Their symbiosis with law enforcement is mutually beneficial. The police get budgets to fight the ‘forests’ and tip off the ‘forest’ about wealthy individuals who can be ripped off ‘for the cause of Islam.’ Beyond that, law enforcement agents improve their statistics by capturing rank-and-file fighters who are of little actual importance to the underground.”

There were several ways of joining the “forest.” One did not have to live in a dugout; the term was figurative, with many members of the underground staying in apartments or working out of offices. And there is nothing sensational in the fact that the group of June 23 attackers included the well-off children of the Dagestani elite — including those of Sergokala district head Magomed Omarov, who oversaw an area that observers describe as one of the least religious in the republic. From the very beginning, the “forest” has always welcomed philologists, IT specialists, and journalists — despite their limited combat abilities. For some, the resistance was a struggle for an alternative state. And if the state had to be Islamic, so be it.

With time, as Muslims from the Russian Caucasus visited Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Egypt, and even Pakistan, they found that the Islam practiced there was quite different from their home variety, simply because of the historical context: Muslims in these countries did not have to adapt to Soviet and post-Soviet realities. These insights were organically woven into the romantic fabric of the many discoveries Russian citizens made abroad in the early 1990s, but no religious dispute with either the state or the mosque followed.

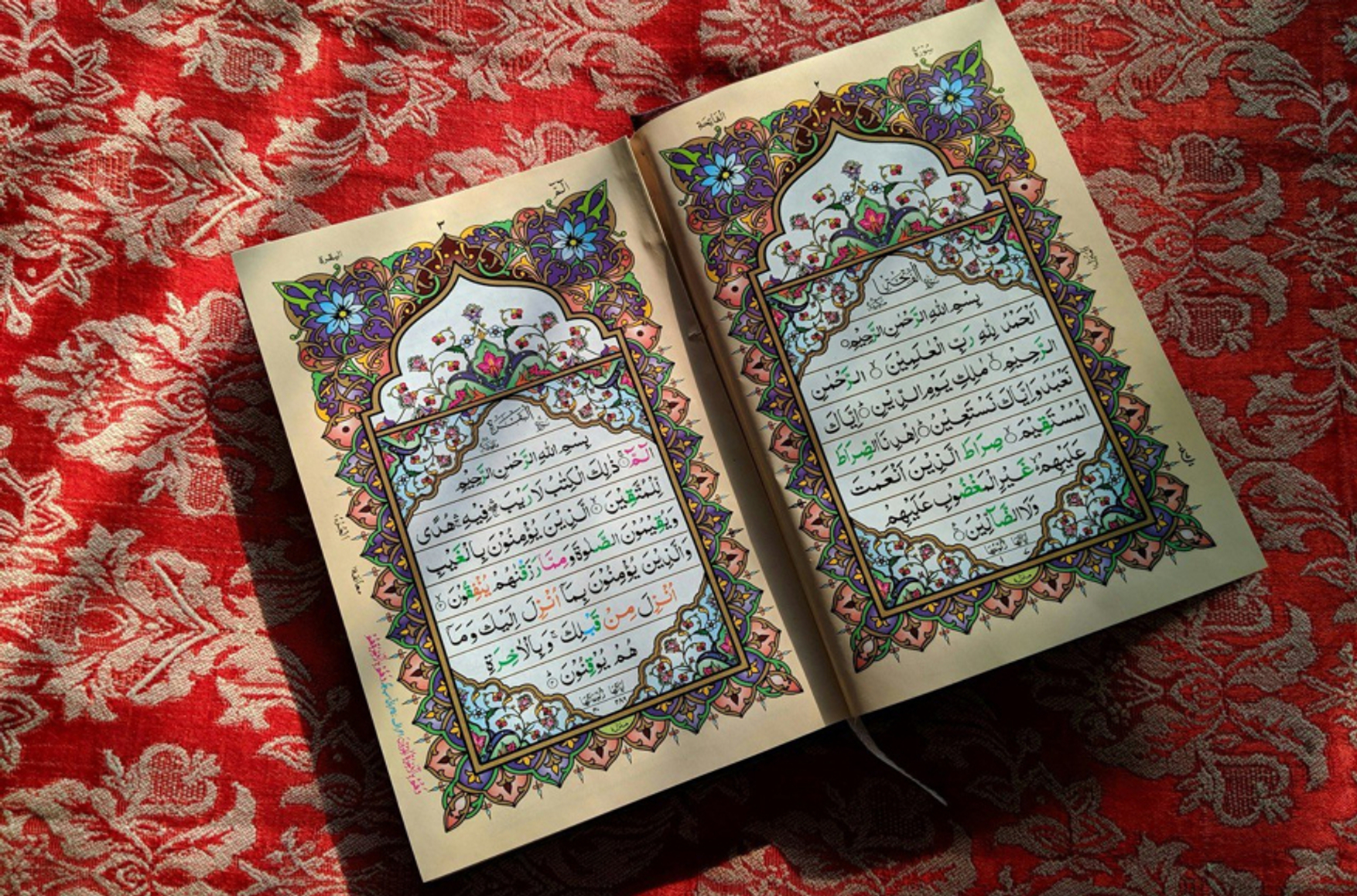

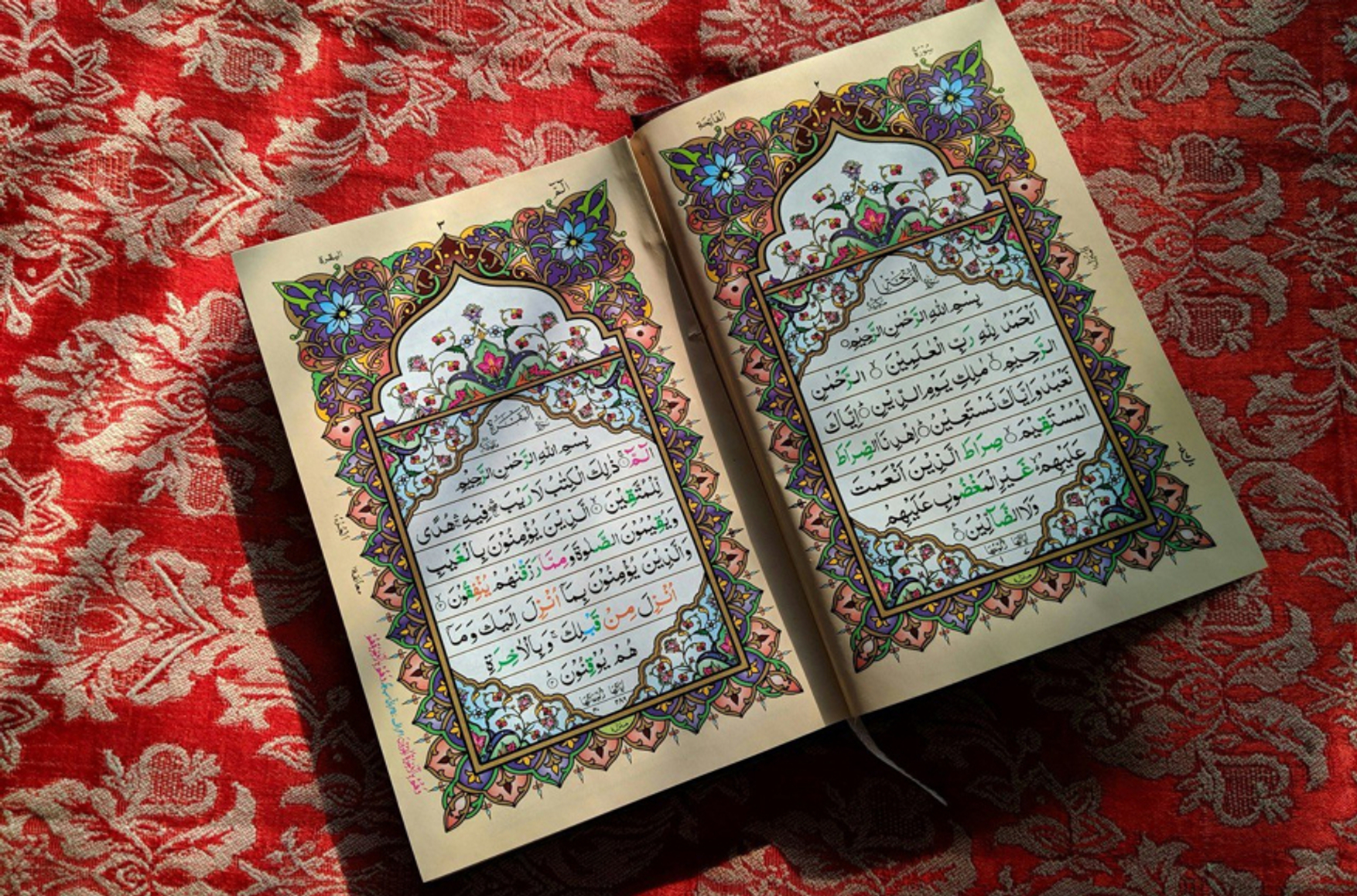

“You can't take from Islam only what you like,” a young man with a secular legal education and two degrees in Islamic law explained to me in a Makhachkala café. “Islam must be embraced in its entirety.” What he meant was that the habit of following the adat, or local customs, instead of abiding by Sharia law, is a vice — and vice must be battled. “You ask what is primary, the adat or Sharia, and it gives you away as an atheist. Essentially, you're saying that tradition was there all along, and then someone came along and wrote the Quran. But we know it was the other way around.” And then he recites another ayah in Arabic...

“You can't take from Islam only what you like. Islam must be embraced in its entirety,” Islamic theologians say

The sociology trap

Most of the armed underground in Dagestan really had been destroyed. The authorities fought the underground at various levels. Under powerful pressure from law enforcement and without external support, militant formations in Dagestan were doomed — just as in Chechnya. The methods used against suspects were merciless, often targeting completely innocent people, up to and including taxi drivers who were suspected of giving rides to Wahhabis. However, the underground’s ideology was not eradicated, and its organizational structures could easily be revived.

At the same time they were attempting to root out violent extremists, the authorities tried to start a dialogue with representatives of non-traditional Islam who did not support waging armed struggle against the state. Interestingly, officials knew the identities of the underground's ideological leaders but did not disturb them unless there was a real need to do so — a clear compromise that remained in effect even after the armed underground was destroyed. After restoring a semblance of order, the local government decided these people no longer represented a threat and could even enjoy freedom of expression — up to a point.

The experience of early Dagestani Wahhabism confirms that local society does not welcome radicalism. There was a world of difference between the first preachers in Karamakhi and Chabanmakhi — peaceful romantic idealists inspired by “true Islam,” who shared their revelations with fellow villagers — and the stern men with assault rifles who replaced them and instilled actual Sharia law in these villages.

There was a world of difference between the first preachers — romantic idealists inspired by “true Islam” — and the stern men with assault rifles who wanted to instill Sharia law

In their article “Dynamics of Religious Beliefs among the Urban Population of Dagestan” (2021), Madina Shahbanova and Anna Vereshchagina state:

“The results of our research have not confirmed the growth of the population’s religious activity in the form of active religious behavior, despite the existing grounds for predicting a significant change in the people’s religious worldview.”

In a nutshell, the more religious people become, the less willing they are to take radical action. The survey included the question “In what kind of state would you like to live?” Even among the responders who described themselves as “convinced believers,” only 50% named an Islamic state, with 42% favoring a secular one. Among “ordinary believers,” the secular state won 58% support, with 26% calling for Islamic law. Among agnostics, 60% favored secular rule, with 9% calling for religious rule.

As the study showed, the secular state, like any modernist idea, wins most convincingly among the young and educated. This is what sociology tells us. Yet, with all due respect, these results may have played a cruel joke not only on the authorities, but also on the people of Dagestan, who believed that the times of religiously rooted turmoil were in the past.

Islamic State 2.0

“If the ‘forest’ consisted only of those striving for a true Islamic state, how many members would it have?” I posed this question to many people, pro-government Dagestanis and those sympathetic to the underground. Strangely enough, both groups gave a similar answer: about one-third of the underground’s actual numbers.

The Islamic underground was a tangled, eclectic structure. Some — the one-third my interviewees referred to — envisioned an “Islamic state” as a beautiful utopia. Many detested the existing state, and they did so for various reasons. Some wanted to fight corruption and injustice. Others were at odds with the authorities, and whether they felt that other members of the underground were in the right or in the wrong, the “forest” nevertheless provided a perfect hiding place for a wide range of actors. Some were even hiding from blood vengeance — the list of motivations goes on and on. Understandably, this variety did not strengthen the movement, but instead made it easier for the authorities to dismantle it, attributing the victory solely to their official efforts. As for the June 23 tragedy, the officials sincerely see it as a force majeure event, the equivalent of a natural disaster, in which there can be no culprit other than nature itself.

While it certainly is a failure of the powers that be — to the extent that any terrorist attack is a failure of governance — we should also recognize, without exonerating the current leaders, that the groundwork for this event was laid long before the current generation of officials assumed their responsibilities. The mothballed matrix of a squashed underground movement became fertile soil for a mature, well-developed variety of radicalism — one no longer based on the amateur musings of an improvised Islamic state.

However, the June 23 attackers did not need the direct help of ISIS. On the contrary, they probably wanted to show the world they could build an ISIS of their own, and to do so from scratch. Their choice of the targets — a synagogue and a church — illustrates their core ideology: anti-Semitism and anti-colonialism in its most radical, ISIS-style form.

The perpetrators of the attack wanted to send a message: you can build an ISIS of your own, from scratch

Relatively few people in Dagestan would be thrilled to wake up one morning and find themselves in Raqqa or Gaza. Hating the Israeli military while enjoying life in a secular state is one thing, but finding oneself in the village of Karamakhi at the height of Wahhabism is quite another. The pogroms at the airport last October were largely seen as ridiculous rather than alarming, although the underlying idea was relatable: the Palestinians are indeed brothers, and “our Jews” are nothing like the ruthless Zionists. However, in June 2024, Derbent and Makhachkala saw the creation of a new trend — a merciless and murderous one.

Today's underground has little in common with the “forest” of 15 years ago, which was built on clan rivalries, corrupt policemen, and the pursuits of religious intellectuals — along with a smattering of the ramblings of religious dilettantes. Today’s resistance, however, relies solely on firepower and fanaticism of an increasingly international nature. The movement is no longer interested in recruiting random individuals of disparate beliefs, and the old matrix will be filled with very different types. However, many of those who built the “forest” version of an Islamic state would blend in perfectly well with the group behind the June 23 attacks. One could say they were ahead of their time — and today, time is on their side against a government that still thinks it defeated them a decade ago.