Expectations that the economic, political, and military challenges confronting the Putin regime would ultimately lead to its downfall have not come to fruition. The evolving dynamics of the war in Ukraine, a changing Western viewpoint on the conflict, apparent war fatigue within Ukrainian society, and the condition of Russia's economy invite contemplation on Russia's future – not in the context of a devastating defeat in the “special military operation”, but rather of its conclusion to the satisfaction of the Kremlin's leadership.

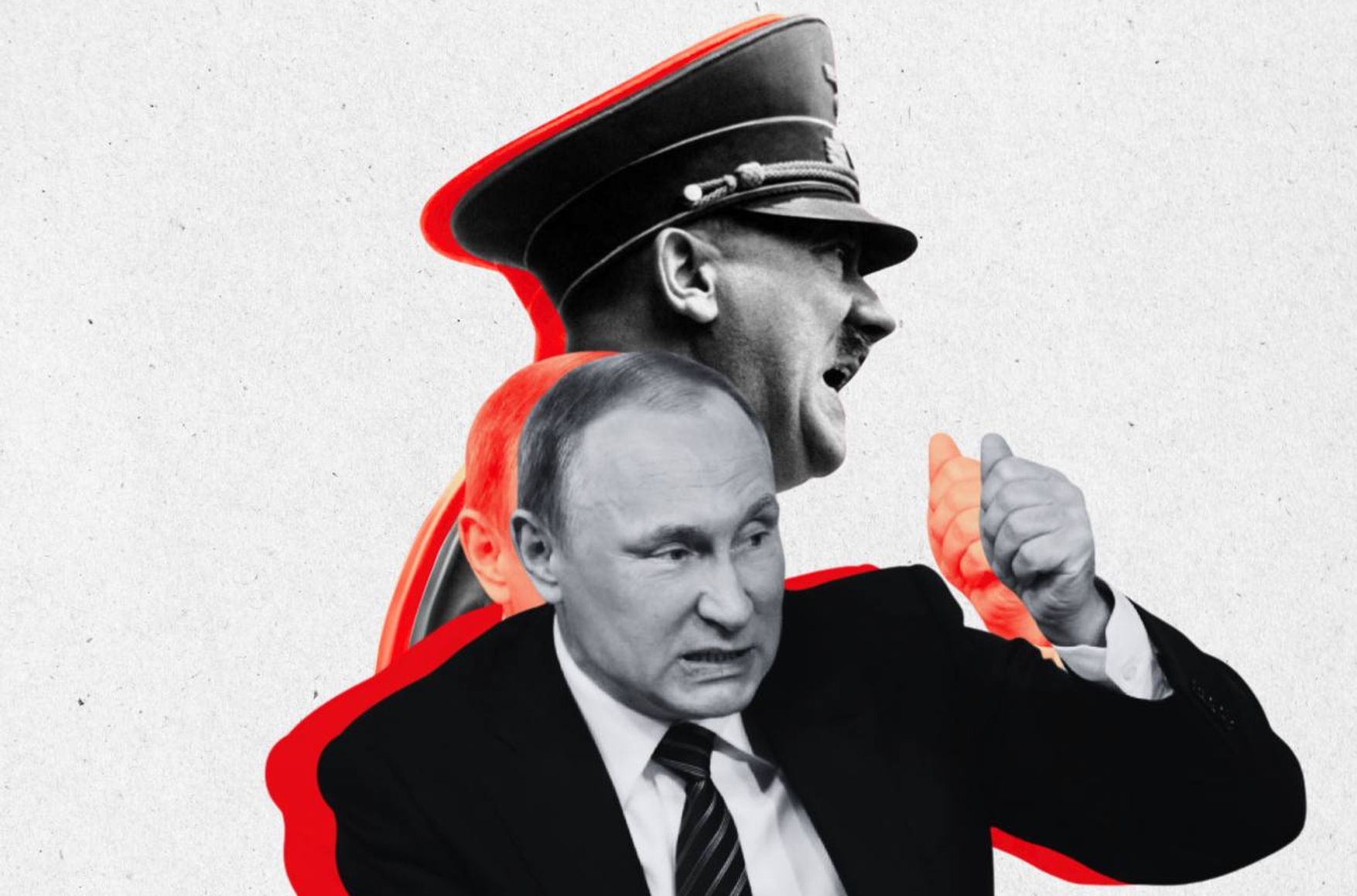

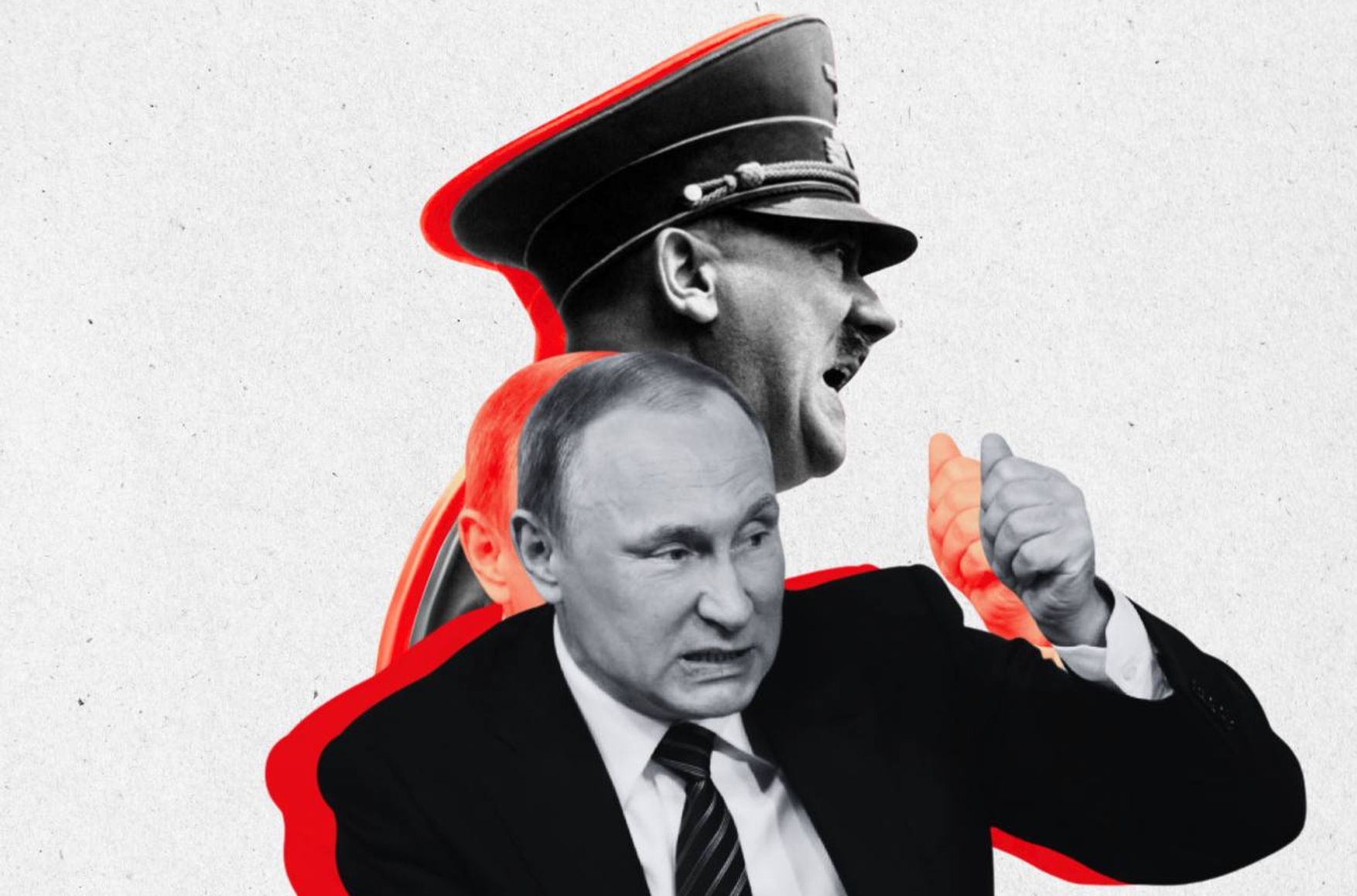

This situation not only urges a cautious glimpse into the future but also prompts a retrospective analysis, attempting to comprehend why Putinism has proven to be so robust and enduring, and why the prevalent narratives of regime collapses seem entirely irrelevant when applied to this context. Reflecting on my characterization of Vladimir Putin's system as embodying various features of a fascist state and maintaining my standpoint, I would like to emphasize a crucial aspect that, in my view, has misled many analysts concerning the nature and prospects of the regime.

Original ideology

In the history of the 20th (and even the 21st) century, we encounter numerous authoritarian and totalitarian systems. Some of them had a more robust ideological foundation, while others had a much weaker one. Some were extremely personalized, while others implied a certain degree of collective leadership. However, they all shared a striking similarity: the main goals of such systems, their relationship with the world and their subjects, their operational methods, and at times, many less significant details were defined before the system's birth—during the period when its ideologues or functionaries were preparing for the seizure of power. Whether they were more original like Mussolini, Hitler, Lenin, or Khomeini, or less so like Franco, Mao Zedong, or Pol Pot, they undoubtedly nurtured their plans for a long time and prepared themselves for their realization.

Thus, upon coming to power—through revolution, rebellion, or even peaceful constitutional means—they followed a clear course, sometimes, perhaps, horrified by the achieved results. Progressing along their predetermined path, they either faced a force greater than theirs or their own weakness—and perished without changing (or occasionally attempting to change).

Against this backdrop, Putin's regime, labeled as “ordinary fascism,” appears to be an extraordinarily unconventional form of fascism.

On the one hand, Robert Paxton's definition of fascism as a

“form of political behavior marked by obsessive preoccupation with community decline, humiliation, or victimhood and by compensatory cults of unity, energy, and purity, in which a mass-based party of committed nationalist militants, working in uneasy but effective collaboration with traditional elites, abandons democratic liberties and pursues with redemptive violence and without ethical or legal restraints goals of internal cleansing and external expansion”

is quite applicable to Putinism in its current form.

In modern Russia, one can easily trace the characteristics outlined by Umberto Eco in his definition of fascism:

- “Cult of tradition” (in our case, “traditional values” or “conservatism”),

- Certainty that “disagreement is equivalent to betrayal” (reflected in the search for a “fifth column” or “foreign agents”),

- “Fear of change” (expressed in reverence for “stability”),

- Emphasis on “anti-intellectualism and irrationalism” (numerous examples of fascination with religion and pseudoscience in Russia),

- “Preoccupation with conspiracy” (where all problems are linked to “hostile forces”),

- “Selective populism” (the Kremlin surpassing everyone in this aspect),

- “Newspeak” and

- “Dissemination of untruths/lies” (a function to which the role of domestic media has long been reduced).

However, despite these parallels, many researchers categorically (and, one would like to believe, not solely due to collusion with colleagues from the Valdai Club) refuse to recognize Putinism as a form of fascism—and there are grounds for such resistance.

Paxton, Robert. The Anatomy of Fascism, London: Vintage Books, 2005, p. 35.

Many researchers categorically refuse to recognize Putinism as a form of fascism—and there are grounds for such resistance

Putin's degradation

On the flip side, the Russian system sets itself apart from any of the 20th-century totalitarian regimes by lacking a singular “core” that permeates its entire existence (the breaking of such a core would symbolize the end of the system). I attribute this to the absence of a “prehistory” for the Russian ruling clique: essentially, before its ascent to power, there not only existed no prevailing ideology for the country's development but also no renowned “elite.” The Bolsheviks, who took control of Russia in 1917, and the Nazis, who rose to power in Germany in 1933, both had a core united through years of struggle—whether legal or, at times, conspiratorial—to actualize their ideas. In contrast, the emerging leadership in Russia was characterized by haphazard connections formed during education, collaboration, or leisure, devoid of any link to political ideals or political strife.

Paxton, Robert. The Anatomy of Fascism, London: Vintage Books, 2005, p. 35.

The emerging leadership in Russia was characterized by haphazard connections devoid of any link to political ideals or political strife

If Hitler, during the «Beer Hall Putsch,» in the mid-1930s, and especially when igniting the Second World War in Europe, openly and clearly expressed his rejection of the Versailles Treaty and the divisive lines it spawned, Putin, in the early 2000s, signed a treaty with Ukraine on inviolable borders and referred to European integration as a source of hope for Russia. If the Kim dynasty came to power in North Korea with the idea of a fully state-controlled economy and will conclude its journey with the same, Putin confidently developed a market economy during his first two terms, attracted foreign investors, and promoted Russia's globalization, only to decisively dismantle everything created during his last years. In other words, the remarkable feature of the Russian version of contemporary fascist politics is its incredible variability.

Paxton, Robert. The Anatomy of Fascism, London: Vintage Books, 2005, p. 35.

The remarkable feature of the Russian version of contemporary fascist politics is its incredible variability

While some Putinism adherents initially developed the concept of a «good Hitler» in the first months after the annexation of Crimea – a Fuhrer who benevolently benefited Germany before the start of World War II – and proponents of perestroika in the 1980s justified the concept of «socialism with a human face» by contrasting the benevolent Lenin to the assassin and tyrant Stalin, all these ideas crumble upon the slightest confrontation with real history, which includes anti-Semitic laws, the elimination of political opponents, the Red Terror, and concentration camps.

In contrast, the “good Putin” is a much more tangible reality: the liberal reforms of the 2000s; an alliance first with the U.S. in the “war on terror” and then closer ties with Europe in opposition to aggression against Iraq; and even the formal adherence to the Constitution when stepping down from the Kremlin in 2008 – all point to this. Moreover, unlike Nazi Germany with its abolition of political parties, North Korea with its hereditary leadership, or Iran with its officially proclaimed theocracy, Russia was, at least until 2012, a relatively democratic country where the population had the formal right to reject dictatorship through voting in various elections.

Paxton, Robert. The Anatomy of Fascism, London: Vintage Books, 2005, p. 35.

Russia was, at least until 2012, a relatively democratic country where the population had the formal right to reject dictatorship

Understanding the essence of the regime was complicated, on the one hand, due to the bold “liberal” maneuvering from 2008 to 2011, and on the other hand, due to its fundamental readiness to cooperate with Western countries and openness to the world, sharply distinguishing it from past and present totalitarian regimes. These two circumstances led Western politicians and experts to consider the system's nature as “hybrid,” while simultaneously “discounting” the significance of signals of its aggression, which became particularly evident in 2008.

As a result, the prevailing view remains that Vladimir Putin is the legitimate ruler of Russia (and this won't change after the upcoming electoral event scheduled for March), that negotiations will be necessary with Putin's Russia, and, most importantly, that the Kremlin is guided in its actions by certain rational arguments.

I reiterate that these perceptions do not seem to be the result of a stubborn unwillingness on the part of their authors to accept the existing reality. Instead, they are born out of the internal dynamism and variability of the Putin system, which, over the past quarter-century, has consistently implemented entirely opposite political lines with equal consistency, sometimes even multiple times, although the change in direction was not always explicitly declared by Putin himself but, for example, by Medvedev. Still, the crucial aspect, in my opinion, is not the complexity of the system's maneuvers but the overall direction of its development.

The inevitable drift towards fascism

Putin's brand of fascism had to grapple with components of a civilized society, not during its ascent to power but after its actual establishment. This delayed its maturation and cast a lasting impact on its overall evolution, considerably muddling our comprehension of the regime's nature. In Mussolini's Italy, the “corporate state” encountered substantial issues within five to six years of Duce's rise to power. Conversely, in present-day Russia, it took nearly fifteen years to deplete economic growth.

If Hitler began his territorial conquests relatively peacefully after five years, and forcefully after six and a half years of becoming Chancellor, Putin delayed these by 14 years. In many other aspects—propaganda mastery, attitudes towards sexual minorities, hatred towards “enemies of the Reich,” recruitment of professionals into the regime, and methods of mobilizing resources for the needs of war and aggression—fascist societies of the past and present turned out to be surprisingly similar. With each new step taken by their leaders, there is less rationality, and the features of similarity increase, with one of them being particularly noteworthy.

Paxton, Robert. The Anatomy of Fascism, London: Vintage Books, 2005, p. 35.

Hitler began his territorial conquests after five to six and a half years of becoming Chancellor, Putin delayed these by 14 years

Sinking into madness against the backdrop of their grandeur and exclusivity, convinced of their own impunity, and adhering to the illusory worldview formed in the minds of their creators, such regimes can exist and develop for quite a long time, even capable of masquerading as relatively normal societies. However, they lack the capacity to revert from madness to normalcy.

In my view, the only relatively prosperous existence for a dictatorship is one in which the maximum level of violence accompanies its emergence and gradually diminishes during further evolution. Examples of this can be found in the histories of Franco or Pinochet. In situations where those in power increasingly immerse themselves in their own falsehoods and are willing to not only dismantle social institutions but also ruthlessly dispose of their own citizens to maintain dominance, their prospects seem quite unequivocal.

Regardless of how convoluted the path of our extraordinary fascism may be, its end will be as inglorious as that of its other versions. Although many were mistaken in the past by categorizing the Russian regime as “hybrid authoritarianism,” it is crucial not to persist in this error—it's time to acknowledge that we have not yet witnessed all the harm Vladimir Putin is ready to demonstrate to the world, and Russia has not yet fully descended into the madness of fascism.

Equally important is not to base conclusions on memories of the “good Putin,” thinking that he may reconsider and once again speak to the world about a “European Russia,” “universal values,” and the hopes he once associated with European integration.

Paxton, Robert. The Anatomy of Fascism, London: Vintage Books, 2005, p. 35.