The prosecution has made its closing statement in the case of Ivan Safronov, a Russian journalist who was charged with high treason for allegedly divulging state secrets to foreign nationals long before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the barrage of politically motivated cases against the press, the opposition, and common Russians opposed to the war. However, there is strong reason to believe his case may have been falsified. The court will pass the sentence shortly, and if the prosecution’s request is granted, he may spend 24 years behind bars. The Insider covers the basics of the infamous case, providing an overview of evidence and circumstances revealed by independent press.

Prosecutor Boris Loktionov has asked the court to sentence Ivan Safronov, a journalist and a former advisor to the head of Russia’s space agency Roscosmos, to 24 years in prison (which is one year less than the maximum term) for the “transmission of classified information” on the Russian Armed Forces, the human rights project Pervyi Otdel reports.

Safronov was detained on July 7, 2020, and was taken into custody. The investigation argued that he had been recruited in 2012 by a Czech secret agent and had supplied classified information to said agent in 2017, sharing data on Russia’s projects of military and technical cooperation in Africa and the Russian Armed Forces’ activities in the Middle East. The ultimate recipient of the classified information, according to the investigation, was the United States.

Since his arrest, the investigators have been exerting psychological pressure on Safronov, not letting him see or even phone his family over the two years of pretrial detention – not even once. Presumably, he intended to use his mother’s visit for “a covert information exchange and to sabotage the investigation”. He was not allowed to receive or send letters for a few months running, and his communication with his defense counsels was also repeatedly impeded, with criminal cases initiated against two of his attorneys during the proceedings. Nevertheless, the journalist has not pled guilty and believes that the criminal case against him is a means of repression for doing his job as a journalist.

Safronov has not pled guilty and believes that the criminal case against him is a means of repression for doing his job as a journalist

Ivan Safronov worked for the Kommersant Publishing House and authored several high-profile pieces on the Russian army, defense industry, and space endeavors. In 2019, he wrote about Russia supplying fighter planes to Egypt. An article titled “Su-35 to reinforce Egyptian power” reported that Russia had signed a contract with Egypt for a shipment of over 20 fighter jets for some $2 billion. The article was published but was taken down before long. The fate of the contract remains vague despite the fact of its signing. Even though the aircraft have been built, analysts believe they are yet to be delivered to Egypt.

Importantly, it was Safronov’s article that may have caused the parties to abort the deal. The contract became public knowledge, advertised across all major media outlets, along with photos of the planes already built for selling. When Safronov’s piece was published, the Egyptian Chief of the General Staff was in the US on an official visit. Livid, he penned a letter to Russia’s Federal Service for Military and Technical Cooperation, writing that Kommersant's piece had “put the high command of the Egyptian Armed Forces in an awkward position”. On the day of publication, General Mohamed Mansi, the Egyptian Defense Attaché, wrote to Moscow, requesting that the Russian party “take all necessary measures and actions to declare the denial of such aforementioned news”.

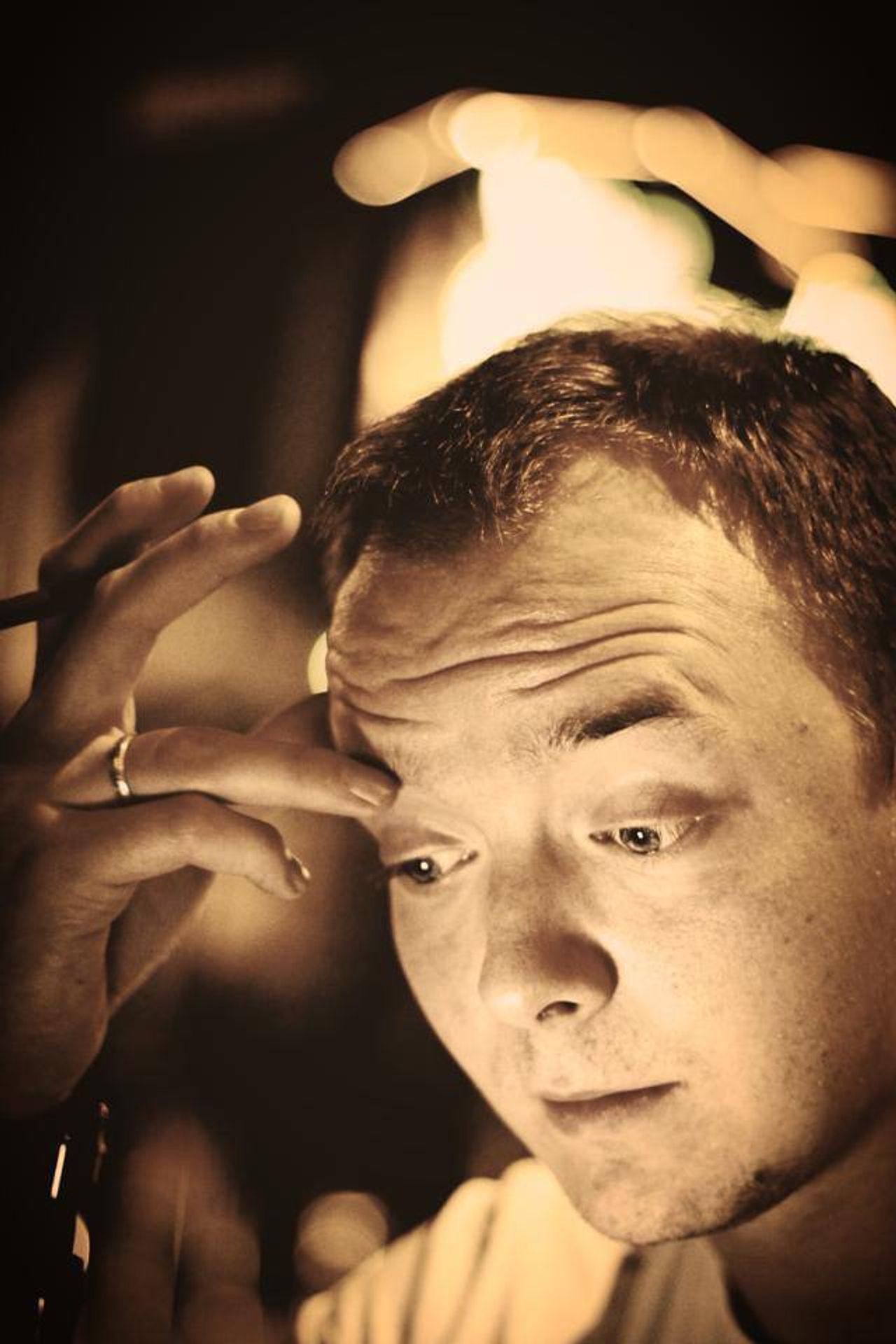

Ivan Safronov at his desk in Kommersant's editorial office. Moscow, January 10, 2016. Photo credit Petr Kassin / Kommersant / Reuters / Scanpix / LETA

Buying Russian fighter jets, Egypt risked suffering from so-called secondary sanctions under the US Countering America's Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA), which stipulates severe restrictions for cooperation with the Russian defense industry. In November 2019, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and the then head of the Pentagon warned the Egyptian government about the consequences of buying Russian fighter jets, promising that major military deals with Russia would “in the very least complicate” similar deals between Egypt and the US.

Safronov’s article that may have caused Russia and Egypt to abort the fighter jet deal in 2019

In the same year, Kommersant fired Safronov for his article about the possible removal of Valentina Matviyenko from her post of Speaker of the Federation Council. The entire politics section resigned in protest over his dismissal. In May 2020, Safronov became the advisor to Dmitry Rogozin, head of the Russian space corporation Roscosmos.

Safronov’s father, Ivan Safronov Sr., was a military correspondent for Kommersant, writing about the Navy and the Army. He mysteriously died in March 2007, falling out of his apartment window. At the time, he was working on a piece on the Russian shipments of Su-30 fighter jets to Syria and S-300V missile systems to Iran. As Kommersant pointed out, the article may have resulted in a scandal. Safronov Sr.'s co-author Mikhail Zygar remarks that the piece was ready for publication but never saw the light of day.

The prosecutors have repeatedly denied that the criminal prosecution has anything to do with Safronov's work as a journalist. Vladimir Putin has also stated that the articles were irrelevant to his case. However, in July 2020, the investigators offered Ivan to disclose his journalist sources in exchange for a pretrial settlement, which he declined.

The media point out that there is no evidence of “criminal activity” in Safronov's case; as the prosecution witnesses have stated in court, he engaged in ordinary journalism and was not “breaking the law or divulging state secrets”. What the prosecution interprets as “high treason” essentially comes down to recounting several articles that had already been in the public domain to a foreign colleague.

Previously, Pervyi Otdel reported that Safronov's defense counsel had been denied a motion for recusal and that the court generally used far-fetched and contradictory grounds to deny the defense lawyers’ motions. According to the journalists, judges D.S. Gordeev, I.I. Basyrov, and O.V. Sharova had a stake in the outcome of Safronov's case. For example, they refused to include Proekt’s investigation and witness statements confirming Safronov's innocence in the case file.

Most recently, Elvira Zotchik, the counsel for the prosecution in Safronov’s case, offered a deal to the journalist during recess: a twelve-year prison sentence for pleading guilty, as Safronov's defense attorney Evgeny Smirnov shared with Mozhem Obyasnit.

Safronov rejected the offer. During the oral arguments that followed, the state prosecutor asked for twice as long a term for him: a total of 24 years in a penal colony for two instances of the alleged crime, a 500,000-ruble fine (~$8,200), two years of supervised release, and the confiscation of “criminal proceeds”.

The prosecution has failed to find the instrument of crime, present witnesses, or determine Ivan Safronov’s motive

Earlier, Proekt published a long read on how the FSB had cooked up Ivan Safronov’s case. Yet again, the journalists confirmed that the prosecution had failed to find the instrument of crime, present witnesses, or determine Ivan Safronov’s motive. All of the “state secrets” allegedly transmitted by Safronov to third persons are available in the public domain.

The investigators detected “classified information” in as many as seven files, six of which Safronov had sent to his Czech friend Martin Larysh and one to political scientist Dmitry Voronin. The files dealt with the military cooperation between Russia and Lybia, Algeria, Serbia, and countries of the CIS and with Russia’s involvement in the Syrian war.

Studying the files, Proekt performed the task that the prosecution never allowed Safronov to do: matched their contents with open sources. The information matched entirely in almost all of the cases, and one case was a close match. Thus, the FSB experts found “state secrets” in an analytical note on Russia’s activities in Syria: the number of troops, the types of weapons deployed, and information on the involvement of specific units in the operation. However, by the time Safronov penned his piece, all of these data had been published by Reuters.

By the time Safronov penned his piece, all of the «state secrets» had been published by Reuters

Safronov’s only meaningful statement that Proekt has failed to find in the public domain concerned the missed deadlines for the tests of reconnaissance satellites Bars-M No.2, Persona No. 2, and Persona No.3. However, the media had long since reported the many issues of Persona satellite series, so the information was hardly sensational. Even less so considering that the Russian court spilled the beans on this matter almost simultaneously with Safronov: the aircraft had been taking so long to build that the manufacturer sued one of the contractors for failure to meet its obligations.

Safronov shared the same information with Larysh in July, amidst the hearing of this case and some six weeks before the court decision was made public. However, he is being charged with releasing the secrets of the Russian state, even though a document containing one such secret is currently available on the court’s website.

He is being charged with releasing the secrets of the Russian state, even though one such secret is currently available on the court’s website

Further proof of the absurdity of the charges is Ivan Safronov’s allegedly offending email dated 2017, which contains the specifications and numbers of equipment Russia had supplied to the CIS. However, these data had already been published in the Eksport Vooruzheniy [“Weapons Export”] journal back in 2016. Interestingly, its publisher Ruslan Pukhov, who is also the founder of the MOD-affiliated Center for the Analysis of Strategies and Technology, testified against Safronov as a witness for the prosecution.

Every single witness for the prosecution insists that they never shared any classified information with the journalist, but this contradiction has done nothing to impede the investigators.

Finally, the highlight of Proekt’s piece is the full text of the indictment made available to the general public (in Russian). The indictment suggests the following: the FSB has ultimately failed to identify the instrument of the crime, its immediate witnesses, or the defendant’s motive.

Nevertheless, Ivan Safronov could be sentenced to an immense prison term of up to 25 years in the nearest couple of days. Here is how the journalist summed up the most recent developments in his case:

“What the defense is presenting as proof of my innocence debunks all the charges against me so utterly and completely that they begin to seem absurd at some point. And yet... I can’t tell you how much longer this will take, but I still have faith and continue to hope for the better. How else could I go on? I know that the entire hassle has to do with my work as a journalist, so I haven't given up. And I’m still not giving up. And I never will. Take care!”