The first major missile strike on Ukraine in 2023 led to a horrific tragedy in the city of Dnipro, where a Russian Kh-22 missile hit a high-rise apartment building, killing 45 people and injuring more than 70. Back in 2014, Europe and the US introduced a broad set of sanctions to restrict access to their electronics by Russian manufacturers of weapons, including high-precision missiles and drones. After the full-on invasion began in February 2022, the sanctions were escalated to a full embargo, but Russia still produces weapons that feature Western electronics and uses them in the war against the Ukrainians. Not only does the flow of chips continue, but it has also increased in volume due to gray schemes and re-exports from third countries.

Content

“Western Electronics at the Heart of Russia's War Machine”

When electronics kill

How the Kremlin works around sanctions

Unsustainable Russian electronics

“Western Electronics at the Heart of Russia's War Machine”

Such was the title of a report released in August 2022 by the UK’s Royal United Services Institute for Defense and Security Studies (RUSI). In the report, the Institute's experts analyzed the technical design and construction of 27 types of cutting-edge Russian armaments, military and special-purpose equipment used since February 2022 in the war with Ukraine: cruise missiles, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), electronic warfare (EW) and signals intelligence (SIGINT) platforms, and tanks.

The examined samples included a Kh-59MK air-to-surface guided missile, a Kh-101 cruise missile, a 9M727 (R-500) cruise missile, a 9M723 tactical missile for the Iskander complex, a 9M549 guided rocket for the Tornado-S rocket launcher, an Orlan-10 UAV, a T-72B3M tank, an Akveduk digital radio communication system, an Azart digital radio station, and a Borisoglebsk-2 EW system. Some of them fell into the hands of the Ukrainian military undamaged, while the rest were debris or preserved as individual units or parts of disabled enemy vehicles or missiles fired at Ukraine.

Foreign microelectronics in the Russian Orlan-10 drone

The Royal United Services Institute for Defense and Security Studies

RUSI experts identified a total of 450 microelectronic products manufactured by companies from the United States, Europe, and East Asia. The vast majority of them – 317 – are of American origin. The runners-up are Japan (34 products), Taiwan (30), and Switzerland (14). Some of them were issued back in the late 1980s, while others date back to 2018 and 2019, when US and EU sanctions on the export of sensitive technology to Russia had already been in place for four or five years.

Most of the Western electronics found inside Russian weapons were produced by US companies such as Analog Devices Inc., Texas Instruments, Intel, and Atmel Corporation. For example, the Russian 9M727 and Kh-101 cruise missiles contained three dozen foreign chips each, including in key system components like onboard computers and guidance modules. In the Orlan-10, Russia’s most successful mass-produced drone, RUSI researchers discovered foreign pressure sensors, navigation modules, microcontrollers, and other equipment.

Most of the Western electronics found in Russian weapons were of US origin

Experts from Conflict Armament Research (CAR), a British nonprofit organization, published a similar report in September 2022, analyzing the electronics in Russian weapons used in combat operations in Ukraine, such as Ka-52 helicopters, cruise missiles, UAVs, and communications equipment. They managed to identify and describe 650 samples of microelectronic products from 144 non-Russian manufacturers. Many of the items were released after 2014, when sanctions were already in effect against Russia; some in 2021.

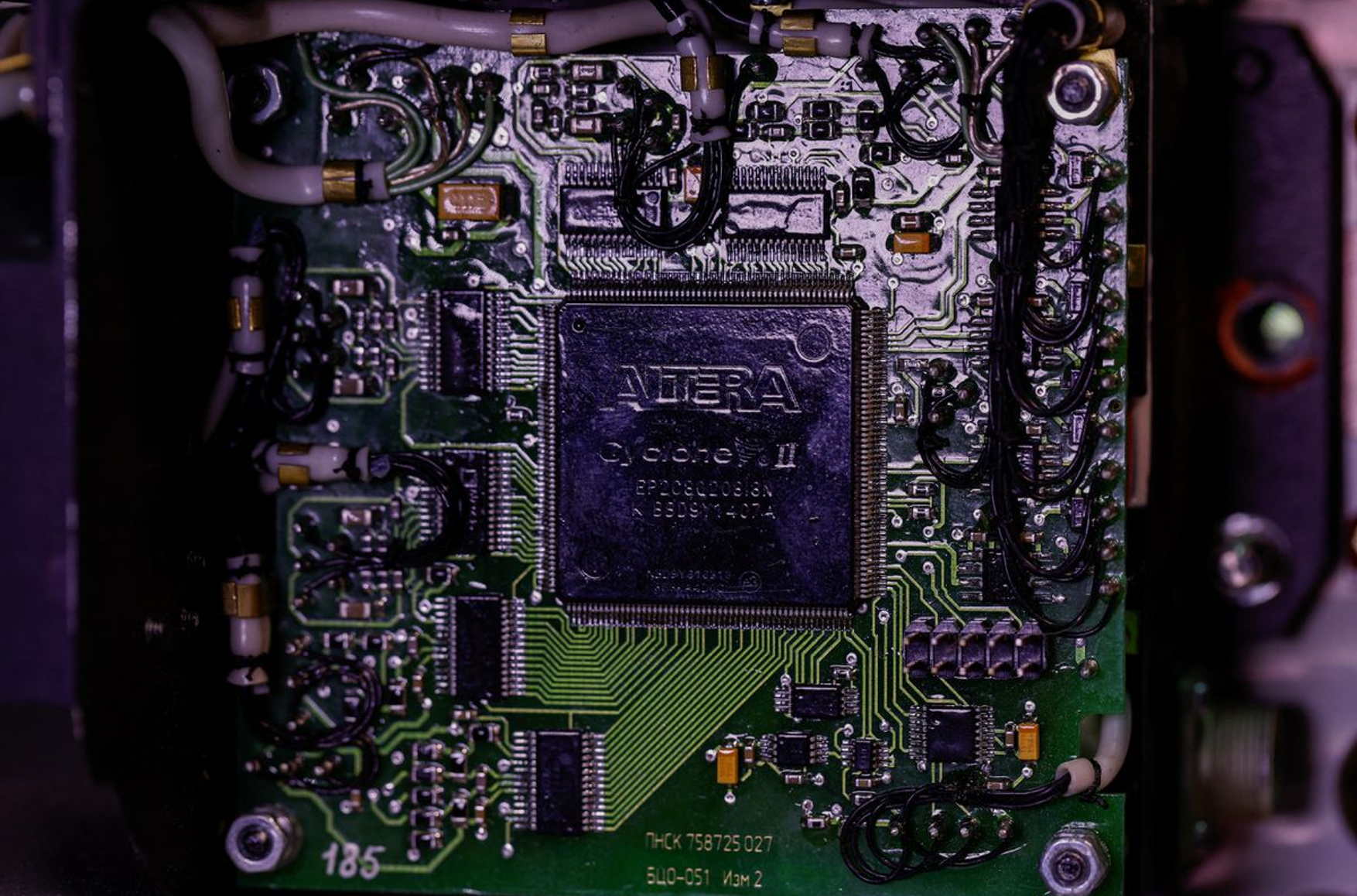

According to CAR, the Russian defense industry uses standard sets of microelectronic components for various weapons systems (control and navigation units, onboard computers, and antennae), relying on a limited set of foreign technologies and apparently lacking any safety net in case if international supply chains are disrupted. CAR investigator Damien Spleeters told The New York Times: “Advanced Russian weapons and communications systems have been built around Western chips,” adding that Russian companies have enjoyed access to an “unabated supply” of Western technology for decades.

Advanced Russian weapons and communications systems have been built around Western chips

In its review of military equipment supplies from NATO countries to Russia, released in June 2022, American NGO Robert Lansing Institute (RLI) emphasizes the breadth and diversity of the range of Western hardware components present in the products of Russia’s military industry, not only in missiles and aircraft but also in individual equipment such as binoculars, rangefinders, thermal sights, and the Ratnik “soldier of the future” infantry combat system.

The conclusions of RUSI, CAR, and RLI about the dependence of Russian weaponry and equipment on Western electronics correlate with the information of the Ukrainian military and volunteers, who occasionally publish data on captured Russian weapons and equipment or disclose it to journalists. In particular, foreign chips were found in the communication equipment of the Barnaul-T air defense target reconnaissance system command-and-control vehicle, the direction finder of the Pantsir air defense system, the automatic aiming system of the Su-24M frontline bomber, the fire control system of the BMD-4 infantry fighting vehicle, the Kartograf reconnaissance UAV, and many other pieces. According to the Ukrainian initiative Trap Aggressor, investigators have reliably identified a total of 39 types of Russian weapons and military and special-purpose equipment featuring 170 articles of foreign microelectronics or preassembled units by manufacturers from 69 countries.

When electronics kill

In the nine months of the war, Russia struck Ukraine with more than 16,000 missiles and artillery shells. The gravest threat is posed by high-precision missiles. By the estimates of the Ukrainian Defense Ministry, Russian troops fired nearly 4,500 missiles from February 23, 2022, to January 3, 2023, including:

· 1,328 anti-aircraft guided missiles for S-300 systems (used against surface targets near the line of contact)

· 744 9M723 tactical missiles

· 638 Kh-29, Kh-31, Kh-35, Kh-58, and Kh-59 aircraft missiles

· 616 Kh-101, Kh-555, Kh-55SM strategic cruise missiles

· 591 sea-launched Kalibr cruise missiles

· 208 Kh-22/32 aircraft missiles

· 144 Oniks anti-ship missiles

· 68 9M728/9M729 cruise missiles

· 10 Kinzhal hypersonic missiles.

A considerable share of these long-range weapons cannot function without foreign microchips in their onboard systems responsible for in-flight control and normal targeting. Therefore, since unprecedented restrictions on electronics exports were introduced in the spring of 2022, officials and experts in Ukraine, the US, and the EU have repeatedly predicted that Russia would soon run out of high-precision missiles, lacking access to the necessary components for their production.

A “graveyard” of Russian missiles and shells fired at Kharkiv

Konstantyn and Vlada Liberov

As a matter of fact, the US Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS), the government agency authorizing the export and re-export of high-tech military and dual-use articles, established tight control over electronics exports to Russia back in 2014. Following the Americans, the EU soon introduced similar restrictions.

All this time, BIS and its European counterparts have been tightening the sets of restrictions and procedures in place and expanding the list of sanctioned companies and organizations. Since February 2022, the restrictions regime has come close to a full-fledged embargo. Nevertheless, by RUSI's estimates, 81 out of 450 microelectronic items found in Russian armaments are classified as dual-use goods in the US and would therefore require a separate license.

Reuters quoted an unnamed Ukrainian official as succinctly expressing the essence of the problem: “Without those US chips, Russian missiles and most Russian weapons would not work.”

Without US chips, Russian missiles and most Russian weapons would not work

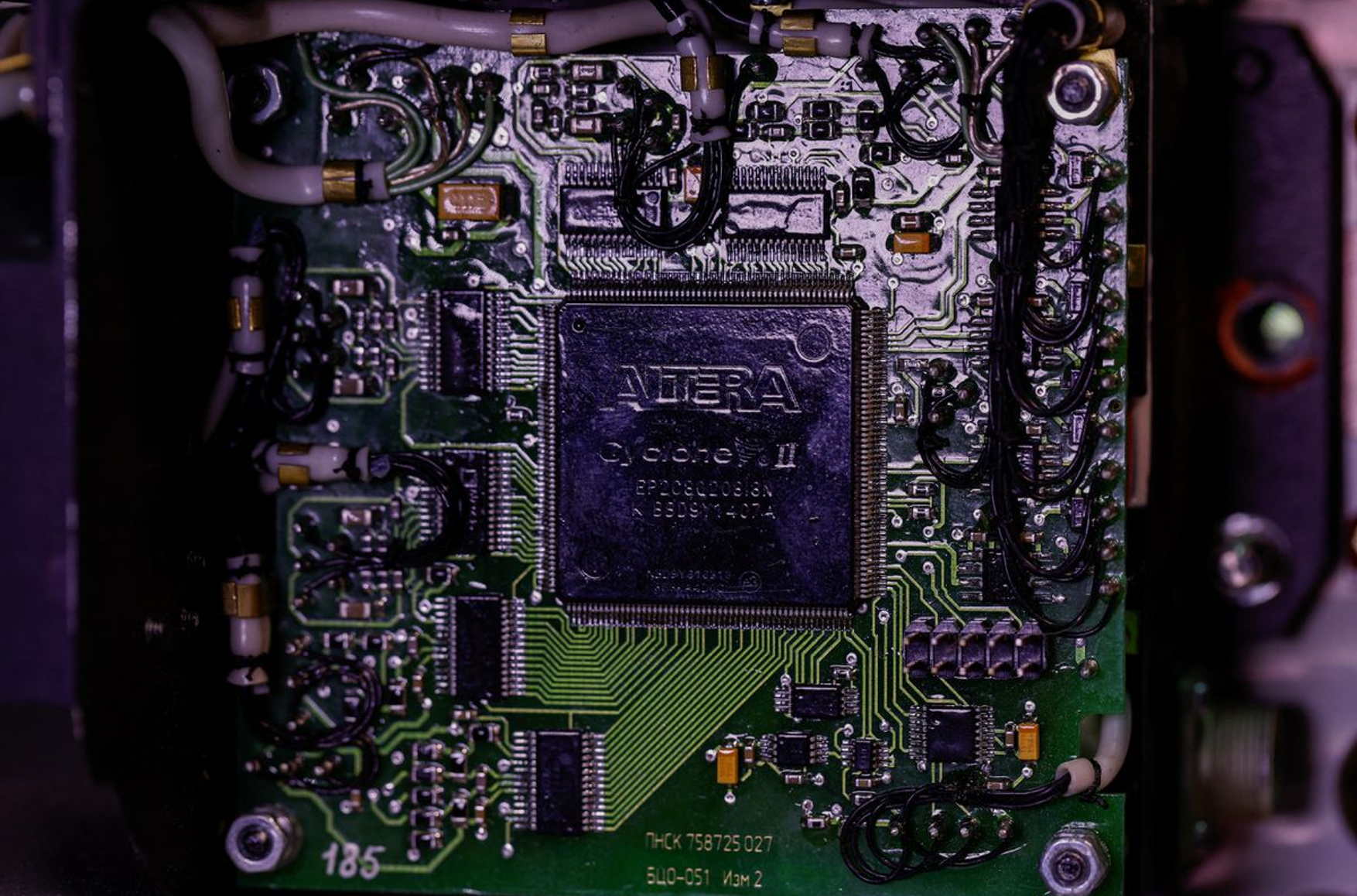

The most in-demand products in the Russian military industry are microprocessors, microcontrollers, Complex Programmable Logic Devices (CPLDs), and Field-Programmable Gate Arrays (FPGAs), which enable the customization of integrated microcircuits for specific tasks.

Electronic components of sensors, navigation systems, and cryptographic and optical equipment are also widely used. Even such seemingly low-tech weapons as armored fighting vehicles rely heavily on Western chips. During the tragic events near Kyiv, when civilians were fleeing from Bucha by car, Russian BMD-4Ms shot at them with incredible precision thanks to sighting systems equipped with a thermal imager and range finder by the French company Thales.

"We'll never run out of Kalibrs!" The Russian MoD’s assessment of the impact of Western sanctions on the supplies of electronics

Russian Ministry of Defense

As for the impact of sanctions, there was indeed a lull in rocket fire last summer, but the Kremlin began a destruction campaign targeting the Ukrainian energy infrastructure on October 10, 2022, with those very high-precision missiles, hoping to deprive Ukrainians of electricity and heating during the cold winter and force the government in Kyiv to negotiate on Russian terms. After another massive raid, the Russian Ministry of Defense, as if in mockery of those who’d hoped for the sanctions to make a difference, posted an illustrative picture titled «We’ll never run out of Kalibrs!” in its Telegram channel.

The first massive missile attack on Ukraine in 2023 involved Kh-22, Kh-101, Kh-555, and Kalibr cruise missiles and Kh-59 guided air missiles and led to a tragedy in the city of Dnipro, where, according to Ukrainian officials, a Kh-22 missile launched by a long-range Tu-22M3 bomber from the air space of the Kursk region hit a residential building. The missile killed 45 people, including six children, and injured 79. The next morning, the Russian MoD Telegram channel posted an equally cynical image, captioned “Charging to the full”.

How the Kremlin works around sanctions

The RUSI report we mentioned earlier suggests that all of the Kremlin's efforts to substitute the import of critical technologies for the defense industry have been failing since 2014. Russia has not been able to develop domestic analogs for Western electronics or procure such analogs from neutral or friendly countries. At first glance, this is indeed the case.

Despite all the efforts to boost the radio-electronic industry through federal target programs (that go back to 2008, pre-dating the sanctions), on the verge of the war in Ukraine, Russia's components for the military radio-electronic equipment lagged behind global standards across all of the crucial categories. From January to September 2022, even at the height of the war, the Russian government covered only 13.9% of the funding required for the Development of the Electronic and Radio-Electronic Industry state program.

Citing internal documents of a Russian research institute, Reuters reported that in 2017, an examination of a promising helicopter-mounted electronic warfare system revealed that out of 921 foreign components needed to start production, only 242 have domestic counterparts. Even the Sarmat strategic intercontinental ballistic missile, with which Vladimir Putin and smaller figures are trying to intimidate the West, may include a share of foreign electronic components.

Bloomberg cited curious data on the progress of import substitution in the defense sector from a classified government report. The document states that the 2025 import substitution program, which covers 177,058 parts, units, and assemblies in 258 types of weapons and equipment, has failed miserably. In 2020, Russia managed to replace only 3,148 components (out of the target 18,047) in five types of equipment (out of the planned 43).

In September 2022, Politico published a no less curious document: a list of foreign microelectronics needs, broken down into three levels of priority, drawn up somewhere in the belly of the Russian bureaucratic beast. The ‘urgent need’ category includes 25 American, Japanese, and German-made chips; some of them have disappeared from the market due to the global shortage of semiconductors, and not because of sanctions.

Be that as it may, the missile attacks on Ukrainian territory have not stopped. The latest waves of massive attacks used cruise missiles manufactured just a few months ago. This could further evidence the reports about Russia exhausting its stocks of missile weapons. However, it could just as well prove the successful work of Russia’s military industry, which has retained the ability to produce technology-intensive products despite all the sanctions and export control regimes.

Russian importers successfully circumvent all restrictions using a variety of tricks and loopholes: engaging intermediaries, using consumer electronics in military products, substituting foreign microchips with hopelessly outdated but functional Soviet components, consciously rejecting more advanced foreign models in favor of less advanced ones, resorting to industrial espionage, and re-exporting through third countries.

Russian electronics importers successfully circumvent all restrictions using a variety of tricks and loopholes

Experts note that many of the foreign chips found in Russian weapons are standard components of general-purpose electronic systems. Weapons often use the same integrated circuits as household appliances and consumer electronics. In May 2022, US Secretary of Commerce Gina Raimondo spoke, citing Ukrainian officials, about semiconductors from dishwashers and refrigerators found in Russian tanks.

Ukrainian experts claim that Russian manufacturers have found a way to integrate household appliance chips even into such complex devices as the onboard computers of high-precision missiles. For example, the microcircuits and microcontrollers experts found in the guidance unit of a 9M544 missile for the Tornado-S MLRS are available for order on the Chinese online marketplace AliExpress.

Electronic components used in several types of Russian missiles and guided projectiles

Conflict Armament Research

Paradoxically, modern Russian weapons such as the Kh-101 cruise missile combine Soviet microchips from the 1960s and 1970s with Western components. While this appears to be a viable option for reducing dependence on foreign electronics (some experts believe that the Kh-101 can be produced without them at all), this approach is coupled with a significant reduction in accuracy and reliability.

Another explanation for the continued production of advanced military products amid the sanctions is the stocks of electronics made before the war. Janes, a renowned defense intelligence firm, prepared a report for The New York Times on the possibility of Russia deliberately hoarding critical components since 2014. Since some of them are categorized as civilian products, supplies could also be arranged legally or via third countries. Furthermore, Russian defense enterprises appear to have obtained some of the electronic components through the SVR and GRU agent network.

Finally, the crucial source of electronics for Russia's military industry is regular imports. The Russian Federal Customs Service (FCS) has been keeping a lid on detailed import and export statistics since April 2022 – in part to impede the assessment of the impact made by sanctions imposed by the West on high-tech goods and electronic components. Nevertheless, Reuters gained access to Russian customs reports covering the period from February 24 to late May and discovered over 15,000 transactions involving Russia's imports of Western electronics from AMD, Analog Devices, Infineon, Intel, Texas Instruments, and other manufacturers.

The crucial source of electronics for Russia's military industry is regular imports

A more complete picture was later presented by well-known economist Maxim Mironov, who published summary data from the FCS database for the first nine months of 2022. According to Mironov, although the imports of semiconductors in the two main sections: “Diodes, transistors and similar semiconductor devices” (Foreign Economic Activity Commodity Nomenclature code 8541) and “Electronic integrated circuits” (8542) dropped sharply in March 2022, they soon recovered to the monthly average of the previous year and even exceeded it. In September 2022, Russia imported $277 million worth of semiconductors, which exceeds the amount imported in September 2021 ($173 million) by more than 50%. Meanwhile, there have been notable changes to the list of supplier countries: the volume of imports from the EU and the United States has plunged to a trickle, China’s share has reached 80%, and Turkey and CIS countries made an unexpected entrance to the semiconductor market.

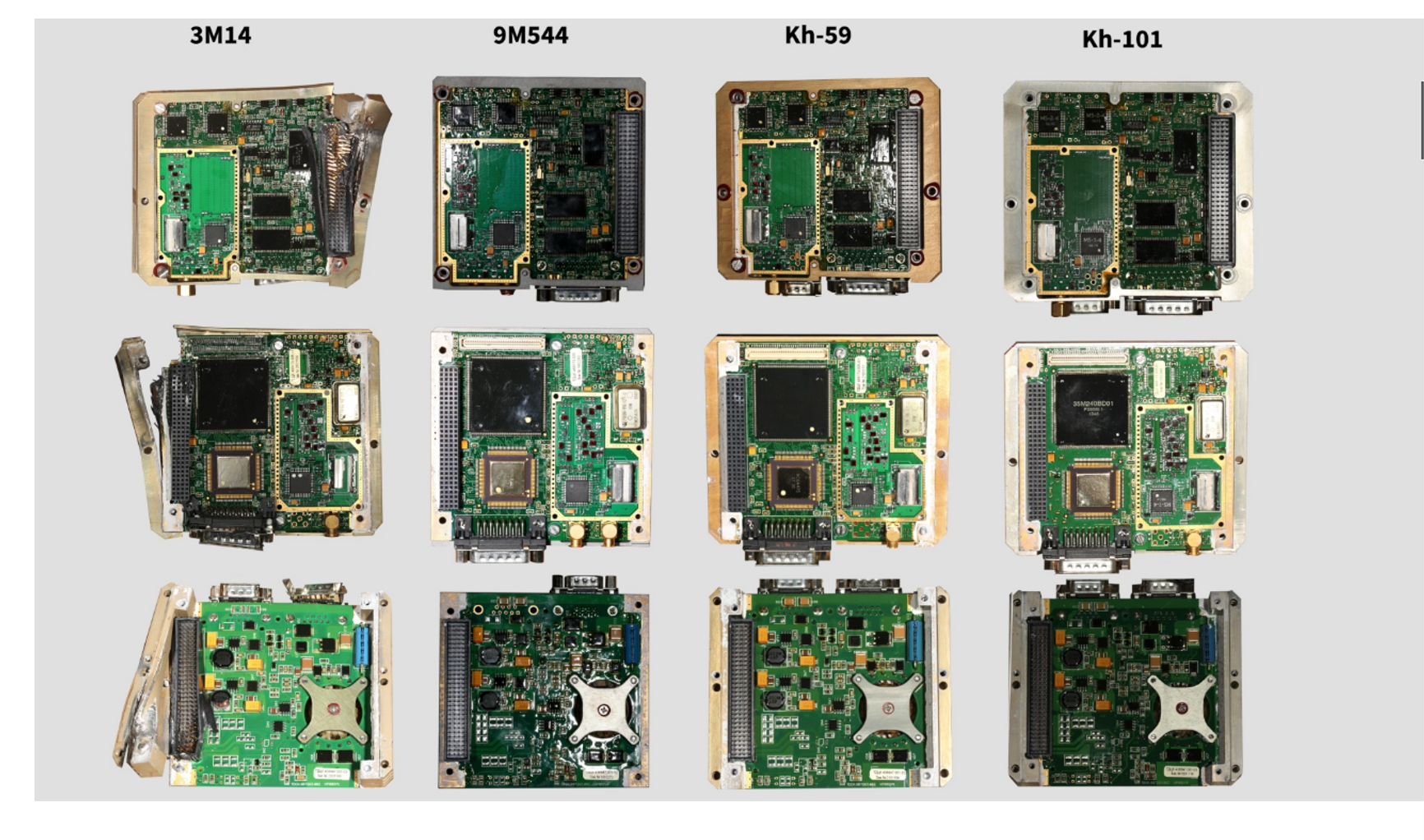

A joint investigation released by Reuters and RUSI in December 2022 exposed Russia’s perfectly functional global network of Western electronics suppliers – despite all the sanctions. Transactions go through intermediaries in Turkey, Hong Kong, and even Estonia (an EU and NATO member) and presumably cover the basic needs of Russian consumers. Citing FCS data, Reuters points out the controversy around the American giant Intel, which announced the decision to stop working with Russian customers on March 3, 2022. Nevertheless, from April 1 to October 31, 2022, $457 million worth of Intel products somehow made it into Russia. A total of $2.6 billion worth of computer and electronics components were imported during that period, with US products by Intel, AMD, Texas Instruments, and Analog Devices Inc., and Germany's Infineon AG accounting for $777 million.

Imports of Intel products into Russia from April to October 2022

Reuters

The situation with Russian weapons is not the only indication that the Western sanctions regime is failing to meet its purpose. CAR analyzed the Geran-1 and Geran-2 suicide drones captured by the Ukrainians. Not only did the experts confirm that these drones (originally named Shahed 131 and Shahed 136) had been developed in Iran, not in Russia, but they also revealed a huge amount of Western electronics. Essentially, all of their principal units and systems are based on foreign components, mostly of American origin. The Ukrainian project Schemes (Skhemy) examined another Iranian UAV used by the Russian forces in Ukraine, the Mohajer-6 reconnaissance and attack drone, and also found microchips by US manufacturers.

If Iran, which has spent decades under sanctions of varying severity, maintains a regular supply of Western electronics for arms production, Russia, which is still much more present in the global market, has no financial problems so far, and can influence foreign politicians and companies through informal networks, is even less likely to struggle in this regard. It seems that in the modern world, any attempts to cut off a major country from microelectronic products are doomed to fail. As long as the war in Ukraine goes on, American and European chips will continue to help kill Ukrainians.

Unsustainable Russian electronics

Ian Williams, Fellow, Center for Strategic and International Studies (USA)

Russia’s newer missiles appear to contain a lot of Western-made components. Many of these are freely available on the market as they have nonmilitary applications, such as civilian electronics and household appliances. We see poor reliability in these new missiles, though. This could be due to poor system integration, and poor quality control of the end product. There have been some confirmed instances of dual-use components in Russian weapons. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing: it comes down to not just the quality of components but the integration of those parts with domestically-produced elements, the quality of assembly, quality oversight measures, and so on. As for the shortage of electronic components, I think China would be Russia’s only significant source. Iran is probably only willing to sell whole systems, like the Shahed-136. Iran is itself dependent on foreign sources for electronic components.

Russia does not have the industrial capacity to produce high-end weapons like cruise missiles at the pace they are using them. Stronger import restrictions will force the Kremlin to look elsewhere for components. Even if it can get new sources, there could be integration challenges and mismatches between parts and the original designs, which will likely lead to lower quality and reliability. This came as a surprise, considering there was a line of thinking that Russia’s defense industry evolved directly from the Soviet defense industry, which was quite self-sufficient.

The author thanks Veaceslav Epureanu for his assistance in preparing this piece.