Nine years ago, the peninsula of Crimea was illegally taken over by Russia and “annexed” to its territory through a referendum held under the control of the Russian military in occupied Crimea. This referendum was not recognized by most nations, making it an illegitimate act. The Crimean issue was considered a frozen conflict for a while, and it seemed like nothing could stop Russia from controlling the territory. However, the situation changed after Russia's full-scale invasion, and now, Ukraine and the international community believe that the peninsula's return is essential for a peaceful settlement. Russia is running out of resources to continue the conflict, and recent history suggests that violent territorial conquests are no longer viable.

Content

The Crimean roots of the war with Ukraine

Plans for the return of Crimea

Territorial gains are a thing of the past

What awaits Crimea?

“It was Putin who closed the door to a diplomatic settlement of the Crimea issue by invading Ukraine”

The Crimean roots of the war with Ukraine

In August 2022, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky gave a landmark speech where he quoted the phrase “it began with Crimea and will end with Crimea” written by Crimean Tatar activist Nariman Dzhelyal in a letter. Dzhelyal had been arrested by Russian security forces for allegedly planning sabotage on a gas pipeline. Dzhelyal was ultimately sentenced to 17 years in a strict regime colony. President Zelensky interpreted this phrase as follows:

“To overcome terror, to return predictability and security to our region, Europe and the world need to win the fight against Russian aggression, which means we need to liberate Crimea from occupation. Where it began, it will end. And it will be an effective reanimation of international law and order.”

The occupation of Crimea was undoubtedly a crucial moment, triggering a series of significant developments. In Ukraine, it marked the beginning of Russian aggression that soon spread to the Donetsk and Luhansk regions. In Russia, it established the “Crimean consensus,” which granted Putin newfound legitimacy as an unmovable leader. Meanwhile, for the West, “Crimea is ours” presented the most substantial challenge to the principles of world order since the end of the Cold War.

The Kremlin's decision to invade Ukraine in February 2022 may have been influenced by several factors, including the relatively bloodless annexation of Crimea and the limited response from the West (The sanctions imposed on Russia only affected a small percentage of the country's GDP). Additionally, by that time, Crimea had become strategically important due to its military infrastructure and weaponry, earning it the monikers “unsinkable aircraft carrier” or “military fortress.” This was due to the combination of its geographic location and the various military assets stationed there, such as missile and air defense systems, long-range aviation, ships, and submarines, providing effective control over the air and sea space of the entire Black Sea region.

In February 2022, the Russian military command launched its most effective offensive against Ukraine from Crimea, deploying roughly 25 battalion tactical groups. Within a mere two days, they advanced over 100 kilometers and seized an area larger than Switzerland. By mid-March, the Crimean group of Russian armed forces had captured Kherson, enveloped Mykolaiv, and posed a threat to Odessa. Although it ultimately had to withdraw from the bridgehead on the right bank of the Dnieper and from Kherson, the “land corridor” it had captured remains the most significant military accomplishment.

Crimea has become the primary transportation hub and rear base for troops deployed in the Kherson (along the Dnieper riverbed) and Zaporizhzhia directions, serving as a critical strategic location. It's also a launch site for missile attacks against Ukraine, with 750 sea- and air-launched cruise missiles fired in the first six months of the conflict alone. In addition, it provides repair and maintenance services for military equipment, fuel and ammunition supply routes, and serves as a deployment site for air defense and combat aviation.

Plans for the return of Crimea

During his presidential campaign in 2019, Volodymyr Zelensky campaigned on a platform of peacefully de-occupying Crimea and Sevastopol and resolving the conflict in Donbas through peaceful means. In March 2021, as an elected president, he endorsed the “Strategy for the De-Occupation and Reintegration of the Temporarily Occupied Territory of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and the City of Sevastopol,” which prioritized political and diplomatic methods, as well as military, economic, informational, and humanitarian measures. The “Crimea Platform” served as the primary tool for implementing these measures, gathering a summit of international parliamentarians, experts, and politicians in support of Kyiv's efforts.

Despite declaring their commitment to Ukraine's territorial integrity, the international community, including the United States and the European Union, only resorted to symbolic gestures and imposed limited sanctions on Russia. Additionally, certain circles in the West subscribed to the belief that Moscow had a “right” to the peninsula, citing legal, economic, historical arguments, and “geopolitical imperatives” to justify their stance.

Even despite Russia's attack on Ukraine, both parties' stances on the Crimean issue remained unchanged in the immediate aftermath. One month after the invasion, President Zelensky expressed his willingness to discuss Crimea with President Putin and “search for compromises.” Meanwhile, in December 2022, U.S. Secretary of State Anthony Blinken emphasized the administration's priority of returning territories occupied after February 24, 2022, to Ukraine, while avoiding mention of the fate of Crimea. However, Zelensky's stance shifted away from seeking compromises in May 2022 when negotiations with Russia hit a roadblock. In January 2023, in a speech at the Davos Forum, he unequivocally demanded:

“This is our land. Our goal is to de-occupy all our territories. Crimea is our land, it is our territory. This is our sea and our mountains. Give us heavy weaponry - we will take back our Crimea.”

The United States was highly cautious about Ukraine's intention to reclaim Crimea by military force. Any move to alter the status of the peninsula was deemed unacceptable in Washington and considered n actuala “red line” for Vladimir Putin. For Putin, Crimea represents both a personal achievement and a crucial step towards restoring Russian imperial glory. In more recent times, the Biden administration has been exploring the possibility of using an immediate military threat to the peninsula as a means to facilitate a peaceful resolution, despite the inherent risk of escalation.

Kyiv considers the return of Crimea a necessary condition for ending the war with Russia

The central point of the discussion is that if Ukraine can demonstrate its military capability to launch an attack on Crimea, it could strengthen its bargaining position. While an actual offensive would carry a high risk, including the potential use of tactical nuclear weapons, raising the stakes in this way could be seen as a justifiable strategy. Ukraine and its Western allies may not be able to sustain a long-term war of attrition, making a more aggressive approach necessary. However, even if Ukrainian forces manage to retake all Russian-occupied territories except for Crimea, violent border changes could set a dangerous precedent and create opportunities for future aggression.

Officials in the West appear to be increasingly of the view that the Russian-Ukrainian war will inevitably result in a change in the status of Crimea. This is evident from their rhetoric. U.S. Secretary of State Blinken, for example, believes that accepting territorial seizures could have disastrous consequences, akin to opening Pandora's box. Meanwhile, his deputy, Victoria Nuland, is convinced that Ukraine will not be truly safe until Crimea is demilitarized. Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte has cautioned against believing Moscow's nuclear threats and its supposed “red lines” regarding Crimea. British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak has even promised to provide long-range missiles to Ukraine for possible strikes against military targets in the peninsula.

Officials in the West appear to be increasingly of the view that the Russian-Ukrainian war will inevitably result in a change in the status of Crimea

In early March 2023, Oleksiy Danilov, the Secretary of the National Security and Defense Council of Ukraine, unveiled a revised strategy for the de-occupation of Crimea. The new plan involves changing the order of priority for various measures, namely political and diplomatic, military, and economic. It is apparent that military methods have been given the highest priority, and the ultimate objective is the full restoration of Ukraine within its internationally recognized borders, including the regions of Kherson and Zaporizhzhia, the “LDNR” areas, and Crimea and Sevastopol, which are currently under Russian control.

It is worth noting that Ukrainian politicians and ordinary citizens are in complete agreement on the issue of Crimea. According to a Gallup poll conducted in September 2022, 91 percent of respondents considered the return of all territories lost since 2014, including Crimea, to be a victory. The Kyiv International Institute of Sociology (KIIS) conducted a survey in February-March 2023, which asked Ukrainians to choose between two options: guaranteed Western assistance in the liberation and further defense of all territories except Crimea, or attempting to recapture the peninsula through military means, which would prolong the war and reduce Western assistance. KIIS data shows that 68% of respondents are willing to take the risk and fight for Crimea, while only 24% are prepared to relinquish it.

The potential for the return of Crimea was also influenced by Vladimir Putin himself. Prior to the “referendums” on the annexation of four regions of Ukraine (Kherson, Zaporizhzhia, Donetsk, and Luhansk) to Russia in September 2022, the peninsula could be seen as a unique case and an exception. However, following these events, it is now regarded in the same light as other occupied regions, where the Ukrainian armed forces have successfully carried out counterattacks.

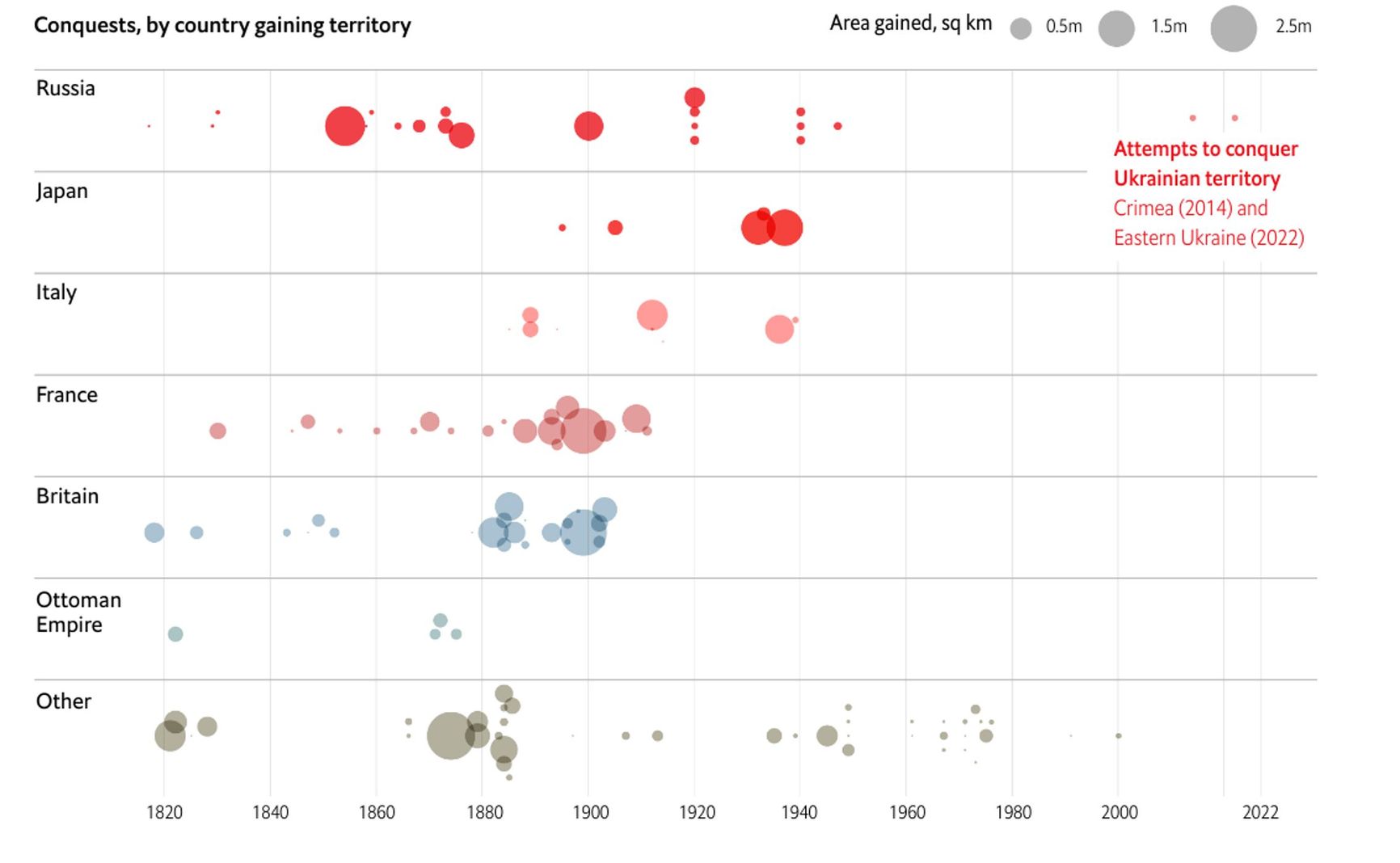

Recent history has also shown that attempts to annex territory through violent conquest typically result in failure.

Territorial gains are a thing of the past

For centuries, wars were waged with the aim of conquering territories and exploiting their resources, whether human or natural. Winning a war meant gaining new fertile lands, subjects, mineral deposits, or access to trade routes, resulting in increased wealth and strength for the victor while the defeated party became weaker and poorer. Economic motives were the primary drivers of territorial seizures. However, since the mid-twentieth century, the situation has changed significantly. First, the frequency and intensity of wars between states have decreased considerably. Second, wars aimed at absorbing or subduing an entire state have become virtually non-existent. Third, attempts to seize a part of another state are now considered a clear anomaly. Moreover, even if aggression were successful, it would often be impossible to justify the annexation.

Stephen Pinker's acclaimed book “The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined” includes the following statement: “Zero is the number of times a country has conquered at least part of another country since 1975.” Although Pinker wrote this before the “polite people” landed in Crimea, his statement was not entirely accurate even at the time of publication in 2011. There were indeed forcible seizures after 1975, but they involved sparsely populated border areas, individual settlements, deserted and/or uninhabited areas, or islands, most of which were uninhabited. According to the Correlates of War project, which has been collecting quantitative data on armed conflicts since 1816, roughly 1% of the world's population changed statehood due to conquest every decade between 1850 and 1940. However, in the last four decades, aside from Ukraine, fewer than 100,000 people, or 0.001% of the world's population, have undergone such a change, with nearly all of them residing in the Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict zone in Nagorno-Karabakh.

History of Conquests by Country gaining territory and area gained Modern Conquest Dataset Version 2.2 / The Economist

One of the prevailing beliefs is that globalization has made territorial wars irrelevant. Non-military methods can quickly eliminate any barriers to participating in international trade and the global labor division. Consequently, all things being equal, armed conflicts over a piece of land can incur more costs than potential benefits. Therefore, even long-term occupations often culminate in a voluntary return to the previous status quo. The most striking examples, comparable to Crimea, are Namibia, the Sinai Peninsula, and East Timor.

Globalization has made territorial wars irrelevant

South Africa has been in control of Namibia, a former German colony, since 1915, initially as a Mandatory Territory, and later as a de facto province, in contravention of UN and International Court of Justice rulings. South African authorities extended apartheid, a policy of racial segregation, and Bantustans, designated areas for indigenous peoples, to Namibia. They also exploited the country's mineral resources and used it as a rear base for troops fighting pro-Soviet insurgents in Angola. In 1990, following sanctions, international pressure, and the dismantling of the apartheid regime, the South African government was compelled to grant Namibia independence.

The seizure of the Sinai Peninsula by Israel after winning the Six-Day War in 1967 against a coalition of Arab countries - Egypt, Jordan, Syria, and Iraq - provides another example of an extended occupation. The Israelis had ambitious plans for the peninsula, which, according to legend, was where God gave Moses the Ten Commandments. They aimed to allocate land to settlers, establish roads and electricity grids, develop agriculture, and invest a total of $17 billion. However, in 1982, Israel withdrew from Sinai to normalize relations with Egypt. Most of the Jewish settlements were demolished, and their inhabitants were compelled to leave for their homeland.

Until 1975, East Timor was a remote Portuguese colony. Following the revolution in Portugal, the local liberation movement declared independence, but within a week, Indonesia dispatched troops and declared East Timor its province. The rationale for this move was the need to unite the two halves of the island of Timor to overcome the oppression of Dutch and Portuguese colonizers. After the resignation of Indonesian dictator Suharto and the initiation of the democratic transition in 1999, a referendum on self-determination for East Timor was held under the auspices of the UN. Almost 80% of residents voted for independence, which was declared three years later.

It is important to note that in each of these instances, the relinquishment of territory was not due to military defeat or the fear of military action. Additionally, Israel and South Africa possessed nuclear weapons, and Indonesia had ample means to defend the annexed territories through plausible pretexts. Similarly to the arguments made in support of the occupation of Crimea, one could justify retaining Namibia based on geopolitical interests, the Sinai Peninsula due to its significant religious importance, and East Timor as a means of correcting a historical mistake. Nevertheless, for various foreign and domestic political reasons, Israel, South Africa, and Indonesia chose to pursue diplomatic solutions rather than maintain their territorial gains.

What awaits Crimea?

Once a favored slogan of Russian nationalists and those who opposed Putin's regime, including those who championed great power, was “Putin may go, but Crimea will remain.” Now, with a full-blown conflict between Ukraine and Russia, a new refrain is emerging: “Whether Putin remains or departs, we will have to relinquish Crimea.” The prevailing view is that as long as Crimea is part of Russia, a lasting peace between Moscow and Kyiv is impossible. Given that there are no diplomatic options for the peninsula's return, military action becomes the primary scenario.

Based on the Ukrainian army's experience in the ongoing conflict, a potential operation to retake Crimea would require a similar offensive to the counteroffensive at Kharkov in August-September 2022, but this time in the Russian-occupied territories of the Kherson and Zaporizhzhia regions, culminating in reaching the Perekop Isthmus. Subsequently, the area of combat operations would need to be isolated by disrupting communications, as the Ukrainian forces did during the liberation of the right bank of the Kherson region and Kherson last fall, such as by disabling the Kerch Bridge. After that, the Ukrainian army would need to establish fire control over the peninsula, similar to the systematic shelling of Snake Island with high-precision artillery systems last summer.

Concrete barriers, aka “dragon's teeth”, on one of the Crimean beaches

To summarize, the Ukrainian Armed Forces will need to combine all their skills, abilities, and military-technical capabilities, which were previously used separately, in smaller theaters of war and under more favorable conditions, in a single operation to retake control of Crimea. However, even if they succeed in doing so, they will only create the conditions for an offensive on the peninsula itself, which presents significant challenges. While fortification lines are being hastily built on the peninsula, its main defense is its geography. With its narrow isthmus only 7-10 km wide, guarding it effectively is a manageable task.

Crimea's main defense is not trenches or concrete barriers, but its geography

If there were to be a breakthrough into Crimea, airborne and naval forces, such as amphibious troops, would be useful, but the Ukrainian military lacks these capabilities. Even with the support of Western allies, it would take too long to create or restore such forces. This is why strengthening the Crimean beaches is seen by some Ukrainians as an embezzlement of budget resources. The only other option is to move across the Sivash, a long bay in the north of Crimea with depths of about 1 to 3 meters, as was successfully done in previous wars. However, this maneuver requires a large number of watercraft and protection from air attacks.

In November 2022, Mark Milley, chairman of the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, acknowledged that the chances of returning Crimea militarily, as opposed to politically, were slim:

“The probability of a Ukrainian military victory defined as kicking the Russians out of all of Ukraine to include what they define or what the claim is Crimea, the probability of that happening anytime soon is not high, militarily. Politically, there may be a political solution where, politically, the Russians withdraw, that's possible.”

However, it is unlikely that Vladimir Putin, as long as he remains the president of Russia, will make a political decision to leave Crimea. Even if Ukraine were to somehow regain control of the peninsula, it would only be the beginning of a difficult process. There are many unanswered questions, such as how to hold accountable those who currently hold positions in the government and municipal institutions of Crimea and Sevastopol.

In essence, the question is what to do with the bureaucrats and municipal employees in Crimea. Should they all be considered collaborators? There are around 36,000 state, military security, and social security workers in Crimea and 48,000 in Sevastopol. If we include government employees like doctors and teachers, the number swells to several hundred thousand.

The question also arises as to how to conduct new elections in Crimea, given that the majority of current officials held positions before the occupation. Would candidates representing the interests of the Russian-speaking population be allowed to participate in the elections? If not, how would this align with democratic principles? Discrimination based on language or ethnicity could lead to tensions, violence, and instability in the long run.

How should the issue of Russian citizenship of residents of Crimea and Sevastopol be addressed? Specifically, what should be done with those who have moved there since 2014, estimated to be between 500,000 to 800,000 people according to Ukrainian sources? Should they be deported, which would amount to ethnic cleansing? Alternatively, should they be allowed to stay, and if so, how can such a large group of potentially disloyal residents be politically “neutralized”? Even if each deportation case was reviewed individually, the judicial and legal system would be overwhelmed with hundreds of thousands of cases.

In what way should the comprehensive system of legal relationships that arose following 2014 be revised? This encompasses property transactions, court rulings, civil registration, and the like. Is it necessary to nullify all of them simultaneously? Or should they all be recognized at once?

The Insider discussed these issues with Tamila Tasheva, permanent representative of the president of Ukraine in the Autonomous Republic of Crimea.

“It was Putin who closed the door to a diplomatic settlement of the Crimea issue by invading Ukraine”

Given the current circumstances, alternative methods of restoring Crimea and Sevastopol's jurisdiction to Ukraine that do not involve military action are becoming less relevant. In 2021, the Ukrainian president issued a decree outlining a strategy for de-occupation and reintegration, with political and diplomatic efforts identified as the primary means for achieving this goal. However, It was Putin who closed the door to a diplomatic settlement of the Crimea issue by invading Ukraine. The Russian Federation has consistently maintained that Crimea belongs to Russia and has refused to engage in any negotiations on the matter, insisting that Sevastopol is a Russian naval city.

In 2021, we undertook a new challenge and established the “Crimea Platform” as a means of facilitating communication, information exchange, and negotiations on the topic of Crimea. Our partners also joined this initiative. Despite the ongoing war, we continued to prioritize and intensify our efforts in 2022, convening a second summit and even a parliamentary summit of the CP. As a foreign policy instrument, the «Crimea Platform» has become a crucial platform for discussing Crimea-related issues. In 2021, the Russian Federation was invited to join the “Crimea Platform“ to discuss the de-occupation of Crimea. Of course, the Russian Federation declined to take part.

The idea of implementing a transition period for Crimea and Sevastopol or conducting a referendum under international supervision is not being entertained. There are no plans for holding additional elections or referendums. Instead, a military administration under Ukrainian control will oversee a transition period because the regular governing bodies in the region won't be able to resume operations immediately due to years of occupation.

In accordance with the Ukrainian Constitution, regional referendums are not permitted in principle, and the 2014 referendum that determined the status of the territory violated international law, the Ukrainian Constitution and our legislation. As a result, we will not engage in any negotiations with Russia on the territory's status, even under the auspices of international guarantees. This stance is shared by the president, all branches of government, and the Ukrainian people, and is a fundamental position on this issue.

No negotiations on Crimea — this fundamental position is shared by our president and the people

We have a clear and unwavering stance on Russian citizens who have settled in Crimea illegally since 2014. Our position is that all such individuals must vacate the territory, as it belongs to the sovereign Ukrainian state. After leaving Crimea, they can apply for temporary residence permits under Ukrainian law by submitting the necessary documents to the Ukrainian migration authorities. While we cannot guarantee that such requests will be granted, Russian citizens will have the right to make this request.

We acknowledge that each case is unique and will be assessed accordingly. We are aware of situations where the spouses of political prisoners were in the process of acquiring Ukrainian citizenship, but were unable to complete the process before the events of 2014. As a result, they were effectively residing in Crimea illegally, with no other means of obtaining an official residence permit. Additionally, there are Russian lawyers in Crimea who have come to defend political prisoners. We are familiar with some of these lawyers residing in Crimea, they are simply helping Ukrainian political prisoners persecuted by the Kremlin. Each case will be evaluated on an individual basis.

For the most part, individuals who did not aid in supporting the Russian occupation regime in Crimea, construct military facilities, particularly in protected areas, breach oaths, commit war crimes or other serious offenses, make managerial decisions or hold high-ranking official positions, or work for the occupation's law enforcement agencies or judicial bodies, need not be concerned. Generally speaking, we are presently developing a set of criteria to establish responsibility in these cases.

Individuals who did not aid in supporting the Russian occupation regime have nothing to worry about

We are aware that life persisted in Crimea during the occupation, with people being born, residing, and even establishing businesses there. In many instances, they had to interact with the occupation administration. The majority of teachers and doctors were simply fulfilling their duties throughout the occupation. Of course, we will not prosecute anyone for these activities. Rather, we will hold those accountable who are deserving of it, including those who have committed human rights violations, war crimes, stolen Ukrainian resources, and the like.

Regarding those who obtained Russian occupational passports after the occupation of Crimea, our position is as follows: according to Ukrainian law, individuals who resided in Crimea in 2014 and held Ukrainian citizenship are recognized as Ukrainian citizens by the Ukrainian state. There is a specific procedure for renouncing or revoking Ukrainian citizenship, and we understand that the vast majority of Crimean Ukrainian citizens did not exercise this option. Therefore, according to our laws, they are still considered Ukrainian citizens. On the other hand, the Russian Federation automatically imposed citizenship on individuals in Crimea, which is a violation of international humanitarian law.

For Ukraine, anyone who held Ukrainian citizenship at the time of the occupation remains a Ukrainian citizen, regardless of whether they were issued a Russian passport after the annexation. Thus, obtaining a Russian passport illegally will not lead to prosecution, as it is not recognized as a valid document by Ukraine. We aim to encourage those who left Crimea after the occupation to return and assist in rebuilding the economy, social, and humanitarian spheres, and we will provide support to our Ukrainian citizens in any way possible.

For Ukraine, a person who received an illegal occupational Russian passport, but did not surrender his Ukrainian citizenship, remains a Ukrainian

Currently, we are in the process of creating a set of criteria that will be used to determine whether individuals working in public authorities in Crimea and Sevastopol will face prosecution, amnesty or lustration. Additionally, we are developing a comprehensive strategy to address issues related to property rights, as well as the recognition or non-recognition of judicial decisions. It is important to note that during the occupation of Crimea, one million court decisions were made, and all of these will be reviewed based on Ukrainian legislation.

While all court decisions made on the territory of Crimea are illegal because they are based on occupation legislation, there are some decisions that are particularly absurd and illegal. Examples of such decisions include those related to political prisoners, which we will overturn and release these prisoners immediately after de-occupation. There are also illegal decisions on the adoption of Ukrainian children and the «nationalization» of property. We are currently developing strategies to ensure that all decisions are reviewed, but this process will not happen automatically.

Ukraine is currently making significant efforts to establish a specialized tribunal to prosecute the crime of aggression, and we have already received considerable support from our international allies. When discussing the vision of a Ukrainian victory, an essential aspect is of course the issue of reparations and restoring the damages caused by the Russian Federation. Unfortunately, the Russian people will have to take responsibility for the war that began nine years ago and the full-scale invasion that started in 2022, and this responsibility may last for decades.

Written in collaboration with Veaceslav Epureanu