Putin's hopes that the West will tire of the Ukrainian issue and decrease the volume of aid some eighteen months into the war appear futile. Ukraine is receiving more and more deadly Western weapons, and whereas popular support of Ukraine in the West may not be as high as in the first months of the hostilities, it's still massive: two-thirds of Europeans believe it necessary to continue military assistance. But there are weak links in this chain of solidarity – namely Hungary, Greece, Bulgaria, Cyprus, and Slovakia. And the most precarious link is the U.S., where the vast majority supports Ukraine, but Kremlin loyalist Donald Trump has every chance to return to power.

Content

Mood swings

The “swing states”

Rejection of the West: Bulgaria and Slovakia

Southern Euro-skeptics: Greece and Cyprus

Pre-election polarization in the U.S.

Mood swings

The Kremlin pinned its hopes of waning Western support of Ukraine on the economic troubles Europe was bound to face due to interruptions in energy supplies; pro-government “political strategists” openly voiced these expectations on prime-time TV. Marked by a surge in energy demand, last winter seemed particularly favorable for such an outcome. However, not all of the Kremlin's expectations came true.

Europe and the U.S. indeed faced economic hardship. The war and its implications put the West through a surge in “Putinflation” – price growth across all categories of commodities, especially gas and electricity. In 2022, the year-on-year inflation rate tripled in the EU, reaching 9.2% (that said, it will have probably dropped to 6% by late 2023 and further to 3% in 2024). Due to reduced Russian energy imports, electricity and gas bills hit record highs in the latter half of 2022. By Eurostat estimates, electricity prices grew by an average of 20% and gas prices by 46% compared to 2021.

Regular social surveys also shed light on how gravely the war has affected the welfare of Europeans. Thus, Brussels-based Bruegel Research Institute reports that more than one-third of EU citizens have tapped into their savings and that 70% have changed their daily habits to save energy. Finally, while Europeans unanimously named possible nuclear escalation as the main threat stemming from the Ukrainian conflict last year, this spring's respondents from Germany, France, and Italy (the largest European countries by population) put the soaring living costs at the top of the list.

But to what extent has economic turmoil affected support for Ukraine? Clearly not as much as the Kremlin hoped.

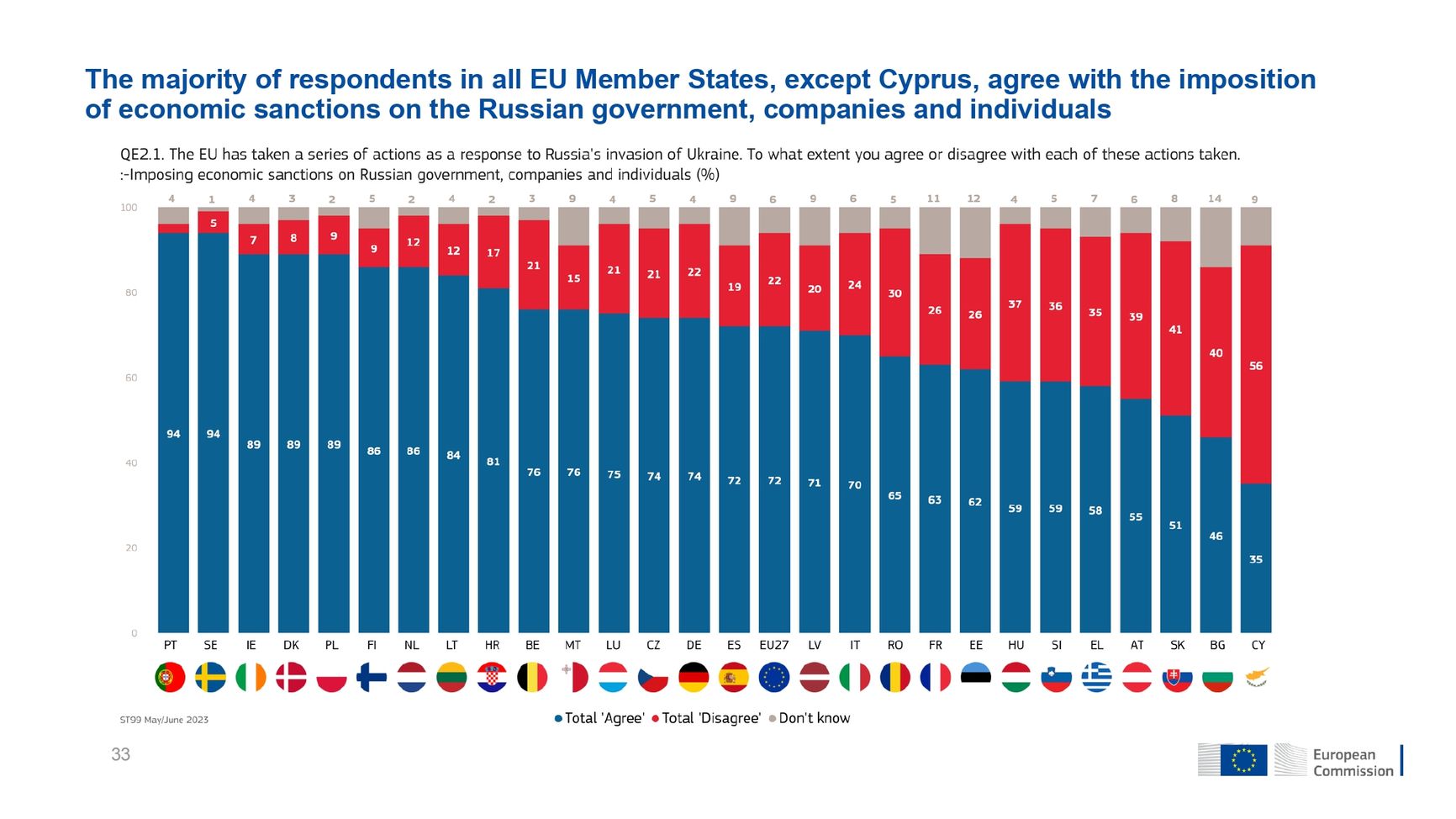

According to European public opinion polls, support for Ukraine has sagged across the board after eighteen months of full-scale invasion – but decreased very slightly and remains at least overwhelming if not unanimous. Thus, according to Eurobarometer, the support of anti-Russian sanctions has dropped from 80% in April 2022 to 72%, and the approval of financial and humanitarian aid to Kyiv weakened from 80% and 93% to 75% and 88%, respectively. Notable declines in support have been registered in Austria, Estonia, Spain, and Italy.

Support for Ukraine has sagged across the board, but very slightly

Sociologists (as well as Kremlin political strategists) pay close attention to the Europeans’ attitude toward Ukrainian refugees. Last March, the EU Council activated the Temporary Protection Directive for Ukrainians fleeing war. Adopted back in 2001 after the Yugoslav wars, the directive had never been applied. The program provides refugees with temporary residence permits, housing assistance, and access to the labor market, healthcare, and education. As of today, more than 4 million Ukrainian residents are under temporary protection in the EU. Germany and Poland received almost one-half of the refugees, but the share of refugees in the total population is the highest in the Czech Republic, the Baltics, Poland, and Bulgaria.

In May 2023, Lodewijk Asscher, the European Commission's former special adviser on Ukraine, presented a report on the integration of Ukrainian refugees into the EU. Reporting on the progress of the Temporary Protection program, he noted that some of the host countries experienced “solidarity fatigue” toward Ukrainians. Inflation has hurt low- and middle-income European families, while the migration crisis has exacerbated many social problems, increased the burden on social services, and caused a shortage of affordable housing and school education. A study by the Slovak think tank GLOBSEC shows that 53% of Central and Eastern Europeans believe that the influx of Ukrainians has deprived socially vulnerable locals of much-needed attention and assistance. Such sentiment is shared by more than half of respondents in Poland, a country that positions itself as Ukraine's closest ally and has hosted about 1.6 million refugees. Interestingly, the Polish right-wing radical Confederation Party, which criticizes the government for caring too much about Ukrainian refugees, has doubled its electoral base since early 2023 and will be the country's third most popular party by the parliamentary elections in October.

Nevertheless, the level of public support and solidarity with Ukrainians remains quite high in European countries, despite high socio-economic costs and general war fatigue. Thus, as the Eurobarometer found in July, 86% of Europeans are still open to their countries hosting war refugees (81% in Poland); 88% consider it necessary to provide humanitarian aid to Ukraine, 75% support the provision of financial aid, and 72% support anti-European economic sanctions. Moreover, 64% of EU residents still favor financing Ukraine's defense procurement and supplying Kyiv with weapons. Swedes (93%), Portuguese (90%), Finns, and Danes (89% each) are the most enthusiastic in this regard. In general, more than half of respondents are satisfied with both national and European responses to the Russian aggression. This allows European politicians to continue to demonstrate solidarity with Kyiv in both words and deeds. “EU-wide persistent public support signals that European citizens understand that the outcome of the war is of critical importance to their own futures,” a Bruegel report sums up.

That said, a closer look at the results of pan-European polls reveals that some countries feature a noticeably less favorable attitude to the policy of aiding Ukraine than the EU as a whole. The ones lagging behind are Bulgaria, Slovakia, Hungary, Cyprus, and Greece. As Dominika Hajdu, the Democracy & Resilience Stream Director at GLOBSEC, told The Insider, Central and Eastern Europe is the most paradoxical in this sense as it also includes countries with the steadily highest support for Ukraine, such as Poland and Lithuania.

The “swing states”

According to the latest Eurobarometer data, less than 50% of Greeks and Hungarians and even less than 40% of Bulgarians, Slovaks, and Cypriots favor providing military supplies to Ukraine. Meanwhile, a GLOBSEC study conducted across eight Central and Eastern European states has revealed that Slovakia and Bulgaria also have the biggest number of those fearful who think that providing military assistance to Ukraine only provokes Russia and brings war closer to their borders. Another crucial indicator is the attitude to NATO and the collective defense principle. Only 58% of Slovaks and Bulgarians are happy about their countries’ membership in the alliance (as compared to 94% in Poland and 79% in Latvia), and only 44% of Bulgarians believe their country should come to the aid of NATO allies in case of an attack. Meanwhile, Greece displays the lowest level of confidence in the North Atlantic Alliance: only 24%; it’s only lower in Cyprus (16%), which is a non-NATO state.

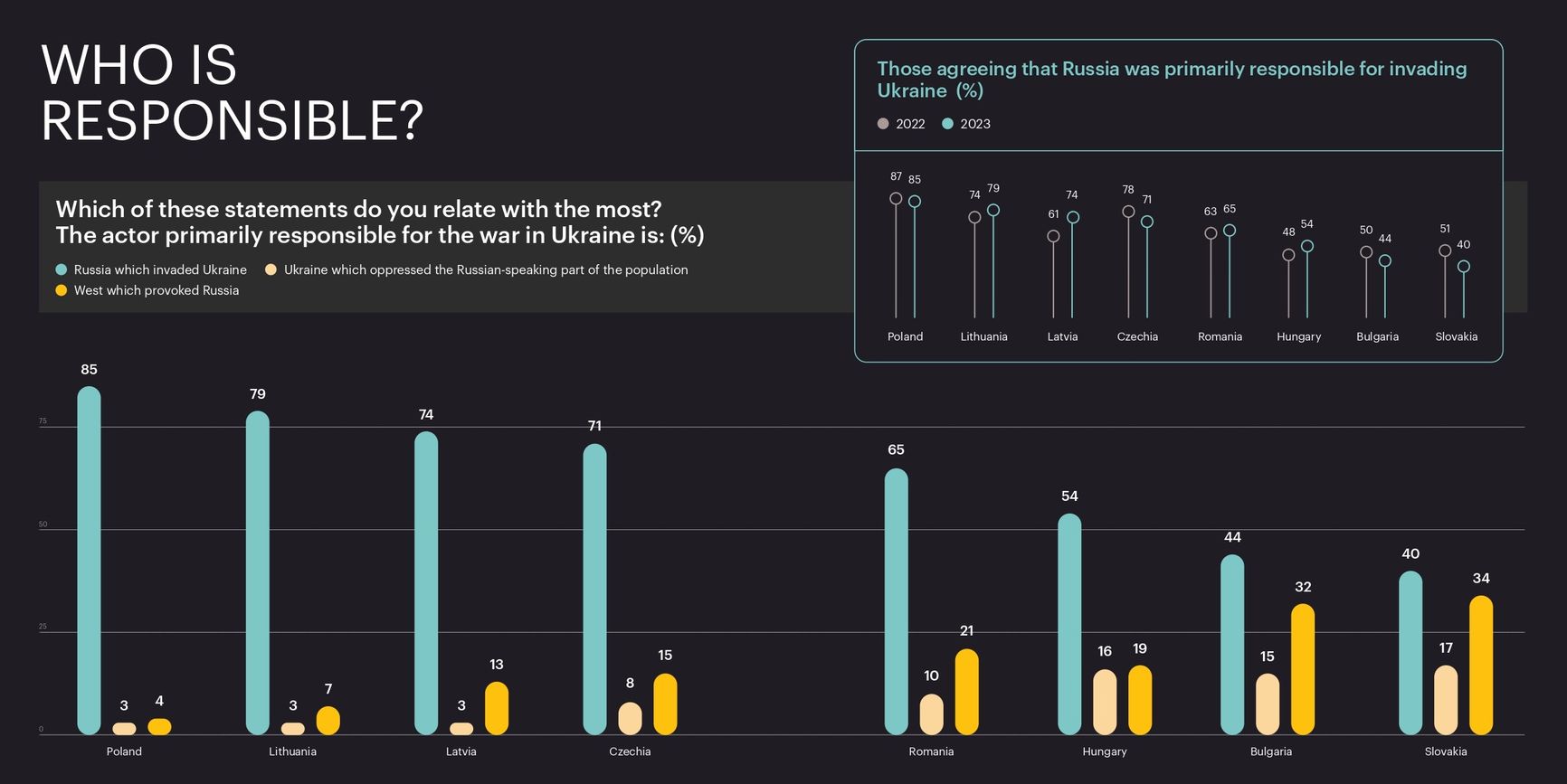

It’s also curious to examine these countries’ perceptions of Russia and the sanctions against it. A quarter of the population of Hungary, Slovakia, and Bulgaria perceive Russia as a strategic partner. In explaining their position to sociologists, Hungarians and Slovaks cited primarily dependence on Russian energy resources, while Bulgarians more often pointed to common history and cultural proximity. Moreover, the share of Bulgarians and Slovaks convinced that Russia bears primary responsibility for the war has shrunk this year. Only 44% of Bulgarians (vs. 50% in 2022) and 40% of Slovaks (vs. 51% in 2022) currently agree with this premise, with over a third of respondents in both countries blaming the collective West for provoking the Kremlin. To compare, even in Hungary, 54% of respondents view Russia as responsible, despite Prime Minister Viktor Orban’s anti-Ukrainian rhetoric, while in Poland the figure is 85%. As for anti-Russian sanctions, the lowest level of their approval has been registered in Slovakia (51%), Bulgaria (46%), and Cyprus (35%).

GLOBSEC

Eurobarometer

Analysts surveyed by The Insider note that, contrary to popular opinion, economic losses caused by the war are not the only, and sometimes not the main, reason for the pro-Russian sentiment. Almost everywhere in Central and Eastern Europe, including Poland and the Baltic states, the inflation rate was double-digit last year. However, the decline in support for Ukraine in this region has not been homogeneous, notes GLOBSEC's Dominika Hajdu. The expert considers the long-term effects of pro-Russian propaganda – spread and supported by local media, social networks, and populist politicians – to be a much stronger factor in this region.

Hungary’s presence in the list of “swing states” is quite expected: the country has a long-standing reputation as the EU's “enfant terrible” and Russia’s loyal supporter in confronting the “liberal West”. Since the full-scale war began, Budapest has regularly obstructed the adoption of pro-Ukrainian decisions at the European level. In the last few months alone, the Hungarian government has blocked a joint EU declaration on the international arrest warrant for Vladimir Putin and a €500 million tranche for Ukraine's defense needs. The Insider detailed the foundations of the friendship between Budapest and Moscow and explained how Viktor Orban manipulates public opinion through his near-total control of the media.

Rejection of the West: Bulgaria and Slovakia

Bulgaria has long been influenced by Kremlin propaganda. Dimitar Bechev, a freelance senior fellow at the Atlantic Council and a specialist in Central and Eastern European politics, believes at least a third of its population traditionally holds pro-Kremlin and anti-Western views. The first explanation is the older generation’s widespread conviction of Bulgaria's strong historical ties with Russia. Secondly, the rejection of the West is characteristic not only of elderly post-Communist voters but also of young people who “scapegoat the EU for social and economic ills” at home. As a result, many Bulgarians have chosen their “big Slavic brother” over pro-European Ukraine in the current conflict. This is further evidenced by Putin's approval rating: even today, 32% of Bulgarian respondents in Bulgaria favor the Russian leader (as compared to 21% in Hungary and 2% in Poland). Such sentiment is also fueled by political instability: Bulgaria has held parliamentary elections five times in the past two years. The formerly marginal nationalist Revival Party, which opposes Bulgaria's EU and NATO membership and holds rallies against military supplies to Ukraine, now ranks third in the National Assembly by the number of seats.

President Rumen Radev, known for his openly pro-Russian statements (like calling Crimea part of Russia), also contributes to this perception. According to Radev, providing arms to Ukraine implicates Bulgaria in the conflict, so he calls for a diplomatic solution instead. In late 2022, he branded Bulgarian parliamentarians who voted in favor of providing military support to Kyiv as “warmongers”. Last February, Radev said helping Ukraine with weapons was like trying to put out a fire with gasoline, and recently he spoke even more harshly, accusing the Ukrainian government of dragging out the conflict at Europe's expense. However, despite Radev's arguments, in the first months of the war, Bulgaria covertly supplied Ukrainian troops with ammunition and diesel fuel through third countries. Last July, the parliament approved a proposal by the newly formed government to supply Ukraine with armored vehicles: about 100 Soviet-made armored personnel carriers. This will be Bulgaria’s first public, direct military aid package since the invasion began. Only pro-Radev Socialists and Revival deputies voted against the decision.

Bulgaria covertly supplied Ukrainian troops with ammunition and diesel fuel through third countries

Bulgaria also lags behind other Eastern European countries by the number of those open to accepting more Ukrainian refugees: 64% against the EU average of 86%.

As Nelly Ognyanova, a media law expert and Sofia University professor, explained to The Insider, “There is another attitude ... According to some voices, Ukrainians are here on vacation, driving expensive cars, staying at hotels, and getting financial support from the Bulgarian state, unlike socially disadvantaged Bulgarians.” That said, Bulgarians have welcomed more than 160,000 Ukrainian refugees.

The rare sparks of resentment are fueled by politician's populist statements. Thus, Revival Party chairman Kostadin Kostadinov claims that the government has allocated almost 1 billion leva (510 million euros; the actual amount is many times less) “to support Ukrainian tourists” and promises to expel refugees from the country if he comes to power.

Nelly Ognyanova explains Bulgarians’ susceptibility to propaganda and disinformation not only by their sympathy for Russia but also by a low level of media literacy: Bulgaria ranks the lowest in European media literacy ratings. About two-thirds of the population get their information from social media, and only one-third trust mass media. In addition, the expert adds, there is still a debate in Bulgarian society about the need for sanctions against pro-Kremlin media. Eurobarometer confirms the lack of consensus on this issue: only 37% of Bulgarians support banning Sputnik and RT broadcasting in the European Union (the support is lower only in Cyprus – 28%).

The landscape is similar in Slovakia, where historical ties to Moscow and nostalgia for the Soviet era also fuel pro-Russian and anti-Western sentiment. According to Matej Kandrik, director of the Slovak think tank Adapt Institute, “Socialism for Slovakia meant to a huge degree an important era of modernization. ... Slovakia was transformed from a permanently agricultural to an industrial country, and life expectancy and overall quality of life grew significantly in the socialist years.” Among other reasons, Kandrik cites the general public's vulnerability to misinformation and various conspiracy theories, as well as dissatisfaction with a “very incompetent and chaotic” pro-Western ruling coalition that failed to properly tackle first the COVID pandemic and now inflation and the energy crisis.

Blaming the government for all their woes, people turn to opposition parties that promote anti-Western narratives and favor maintaining good relations with Russia, says the expert. As a result, such views are no longer marginalized.

This is confirmed by the grim results of public opinion polls: only 18% of Slovaks trust their government; about 30% do not support the country's EU membership, and 50% believe the U.S. poses a threat to Slovakia's security by “dragging” it into the war with Russia.

The military aid package Slovakia has pledged to provide to Ukraine is valued at 0.7 billion euros and includes, among other things, 13 MiG-29 fighter jets. However, the snap parliamentary elections scheduled for late September could result in the return to power of left-wing populists from the Direction - Social Democracy Party (Smer). Smer leader, former Prime Minister Robert Fico, calls for an end to arms shipments to Kyiv, promises to veto additional sanctions against Moscow, and argues that Ukraine's accession to NATO will lead to World War III. If Fiсo wins and manages to form a coalition with other parties, Slovakia could form a Kremlin-friendly government, bringing about “a total overhaul of its policy towards Ukraine,” believes Kandrik.

Southern Euro-skeptics: Greece and Cyprus

Relatively low levels of public support for Ukraine since the start of the war have also been observed in Greece and Cyprus. Suffice it to say that, according to opinion polls in the spring of 2022, Cyprus was the only EU member state where the majority of respondents (51%) refused to attribute primary responsibility for the conflict to the Russian authorities. In Greece, the share of such people was also quite large – 45% (against the European average of 17%). Experts at the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR) rank these two countries among the most skeptical about European integration – and the most susceptible to Russian influence. Indeed, more than 50% of Cypriots and Greeks distrust the EU as an institution and are dissatisfied with its response to the Russian invasion.

In Greece, the reasons for sympathizing with Russia are the same: historical ties and Communist heritage. “There has also always been a relatively small but very vocal and culturally almost hegemonic political minority in Greece – including the Communist Party of Greece – that has always opposed the U.S. and the West at large and has supported Russia (previously the Soviet Union),” explains Roman Gerodimos, Professor of Global Current Affairs at Bournemouth University. Led by Alexis Tsipras, the leader of the radical-left Syriza coalition, the previous government also played its part. He pursued a policy of rapprochement with Russia and criticized anti-Russian sanctions as counterproductive back in 2015; some of his top officials “had ties with people like [Alexander] Dugin”, Gerodimos adds. Last year, Tsipras, now in opposition, condemned the Russian invasion but strongly opposed arms supplies to Ukraine, accusing the incumbent Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis of recklessness and dragging Greece into war. He also called Ukraine's Azov Battalion a neo-Nazi formation.

In Greece, the reasons for sympathizing with Russia are the same: historical ties and Communist heritage

Despite the public's criticism of the EU, the Mitsotakis government has yet to deviate from the all-European course. Greece was one of the first countries to send military aid to Ukraine, though 67% of citizens disagreed with this decision in March 2022. And still, in a meeting with Ukrainian Defense Minister Oleksii Reznikov last April, his Greek counterpart Nikolaos Panagiotopoulos assured him that Athens would support Kyiv for “as long as it takes”.

As for Cyprus, its favoring of Russia stemmed primarily from business and financial relations in recent years; more precisely, from the island's dependence on “Russian” money: tourism revenues, investments, and oligarchic capital. Ten years ago, up to 40% of Cypriot bank deposits were of Russian origin. Before the pandemic, Russia was Cyprus’ second largest “supplier” of tourists after the UK, with Russians accounting for 20% of the country’s tourists. In 2020, Russia was responsible for about a quarter (over €100 billion) of all foreign investment in the Cypriot economy. Almost 3,000 Russians obtained “golden passports”, using a gray scheme to secure Cypriot citizenship in exchange for investment. Some of them are now on the Western sanctions lists. For many local businesses, Russians have been important, if not key, clients for years.

Cyprus favors Russia because of its dependence on “Russian” money

Today the republic is trying to shed the image of Russia's “laundromat” and prove its solidarity with the European community – to be “on the right side of history”, as President Nikos Christodoulides put it. And while Cyprus refuses military aid to Ukrainians, citing the need to maintain its national defense potential, President Christodoulides called for continued support for Kyiv at the European Parliament last June. It is a matter of principle “to ensure that the law of the jungle will not prevail”, he said, adding that the high cost of decisions to counter Russian aggression is justified as peace in Europe has to be defended. However, opinion polls suggest that the majority of Cypriots think otherwise.

Pre-election polarization in the U.S.

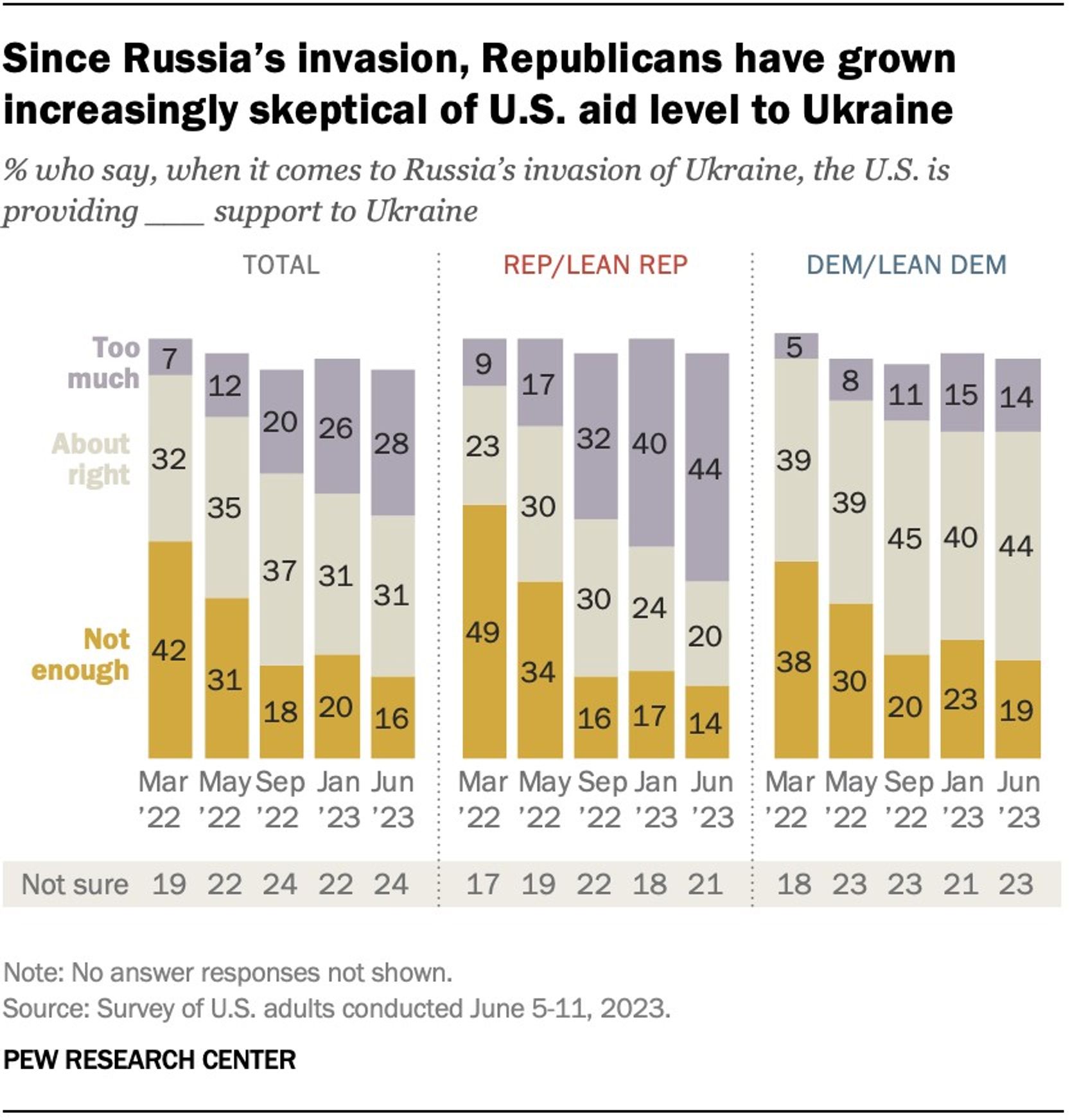

In the United States, the situation is not dissimilar to that in Europe: the level of solidarity with Ukraine and support for the pro-Ukrainian course has somewhat slumped compared to last year but remains high. Importantly, as the 2024 presidential campaign approaches, public sentiment correlates more and more clearly with party affiliation. Although both parties formally favor solidarity with Ukraine, polls show that Republican voters are starting to lose patience more quickly.

The U.S. is Ukraine's main donor, with military, financial, and humanitarian aid received by Kyiv from Washington over the past eighteen months exceeding $75 billion. According to the latest Pew Research Center studies, about 47% of the nation's adults describe current spending as optimal or even inadequate, while about one-third (28%) consider it excessive. Meanwhile, the number of Republicans who believe the U.S. is helping Ukraine too much grew by 150% in the past year and reached 44%. Furthermore, as University of Maryland researchers found in April, 46% of American voters believe it is possible to support Ukraine for another year or two, but only 38% agree to do so for as long as it takes. The majority of conservatives expectedly favored shorter-term liabilities. Overall, 57% of Republican Party supporters disapprove of the Biden administration's response to the Russian invasion.

Whereas about 60% of Americans expressed willingness to pay for Ukraine's support with higher energy prices and higher inflation before October 2022, polls recorded a 9-15% drop on these points in the spring of 2023. American society's attitude toward the Russian threat is also evolving. In the first months of the invasion, half of the country's residents considered it a serious threat to America’s interests, while today only one-third agree, and another third call Russian aggression a minor threat. That said, 64% of Americans perceive Russia as an enemy, and this is something Democrats and Republicans agree on. There is no strong controversy between them on the issue of Washington's goals in the conflict either. Twenty-six percent see the main goal as a return to the status quo before February 24, 2022. Other popular objectives include the liberation of all Russian-occupied territories and the prevention of further advance of Russian troops. Only 8% of respondents favor Russia's weakening or defeat in the war.

Two key factors will influence American public opinion in the near future, comments Shibley Telhami, a nonresident senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and a University of Maryland professor. The first is the frontline chronicles: the more often the American public sees Russia’s battlefield failures and Ukraine’s advances, the more willingly it supports the current course toward Ukraine. In this sense, the next few months could become crucial, given the high hopes inspired by the Ukrainian counteroffensive.

The second factor is the upcoming election campaign: clearly, the candidates will include the conflict in Ukraine and the U.S. involvement in their campaign. However, neither party has a unified position on this issue. Most Democrats approve of President Biden's policies, but some of his moves may spark controversy, like his decision to send cluster munitions to Ukraine. There is no consensus in the Conservative camp either. While Donald Trump and Florida Governor Ron DeSantis, the two main contenders for the Republican Party nomination, criticize the current administration and doubt that defending Ukraine serves America's best interests, former Vice President Mike Pence (also in the race) is more favorably disposed toward Ukraine. One way or another, if the Republicans win the 2024 elections, U.S. aid to Kyiv may be limited, if not stopped altogether. Moreover, any change in Washington's policy could also undermine European unity: as ECFR notes, “Biden has been almost as important to building European unity from a positive direction as Putin has been from a negative one.”

If the Republicans win the 2024 elections, U.S. aid to Kyiv may be limited, if not stopped altogether

While paying tribute to the unprecedented solidarity of the West with Ukraine, experts warn against taking it for granted and admit the sentiment may change in the coming months. If the news from the front indicates that the conflict is dragging out, with neither side capable of winning a military victory, it could undermine public support in both the U.S. and the EU, according to a Breugel report.