As talks continue in Cairo about a temporary ceasefire in the Gaza Strip, Israel is preparing to storm Palestinian militants’ last stronghold: Rafah, where hundreds of thousands of civilians have relocated since the fighting began in October. Before the IDF launched its ground operation, clearing the extensive network of tunnels and bunkers lying beneath Palestinian territory was expected to pose a serious military challenge. Contrary to expectations, armed resistance in northern Gaza was suppressed relatively quickly, and the miles of tunnels did little to help Hamas hold out in previous battles. Six months into the fighting, however, the underground system created by the terrorists and their allies still stands as the main obstacle to a total Israeli victory in the conflict. Hiding in tunnels, the terrorists hope to buy time until the West pressures the IDF to withdraw from Gaza amid a worsening humanitarian crisis.

Content

The underground world of the Gaza Strip

Did the tunnels help Hamas?

Tunnels buying time

What next?

The underground world of the Gaza Strip

Before the start of the IDF ground operation in the Gaza Strip, experts feared that its sprawling system of tunnels would allow Hamas and other Palestinian groups to wage long and bloody urban battles and inflict significant damage on the Israeli army. Before the war, Hamas leadership was believed to have been using up to 95% of all cement shipments to the exclave for its construction of the “lower Gaza,” also known as the “Gaza metro.” The length of underground passageways was estimated to span 400-500 kilometers.

After the start of IDF combat operations, it became clear that the network was much more extensive, technically advanced, and complex than expected. Aside from providing hiding places for the militants and transportation routes for the covert movement of people and cargo, the tunnels also contained command posts, weapons depots, and ammunition production facilities. Some of the corridors were large enough for cars to drive freely inside them, and after clearing sections of the underground city, Israeli soldiers found rooms still fully stocked for a long siege.

In other words, the primitive dens with wooden supports from the early 2000s have been replaced by well-planned and well-built North Korean-style passageways and bunkers. DPRK engineers assisted Hezbollah in building their tunnels in Lebanon, and the latter likely shared this newfound experience with their Hamas counterparts. The militants even tiled the walls in some of the rooms where they were holding hostages.

As of January 2024, the IDF estimates the total length of Gaza's underground network to be between 560 and 725 kilometers, with more than 5,700 entrance shafts. Their construction required 6,000 metric tons of cement and 1,800 tons of steel. The tunnels are located not only beneath hospitals (including the Al-Shifa), mosques, and schools, but also under UN agencies (such as the UNRWA headquarters), farmland, and even cemeteries. The above-ground facilities in the Strip and the subterranean infrastructure turned out to be sharing the same power grid, communications networks, and sewerage system, making them relatively livable. Nevertheless, the immediate combat value of the tunnels appears to have been limited.

Did the tunnels help Hamas?

Subterranean warfare has traditionally been considered one of the most difficult forms of combat, as the typical advantages enjoyed by the side with superior firepower and equipment are mitigated, and attackers find themselves in a vulnerable position due to the difficulty of conducting reconnaissance. However, the widely anticipated underground resistance of Hamas in northern Gaza largely failed to materialize.

The widely anticipated underground resistance of Hamas in northern Gaza largely failed to materialize

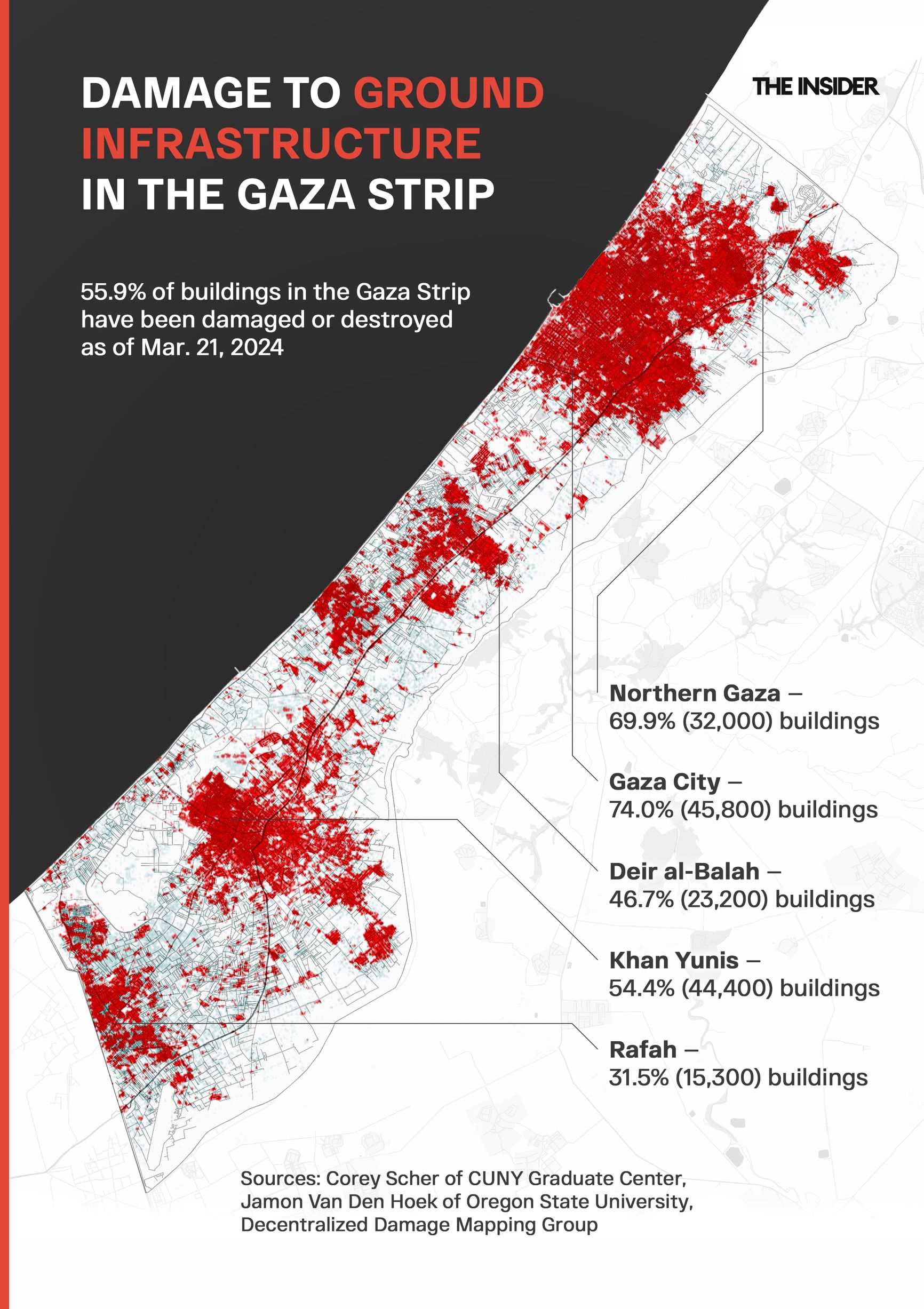

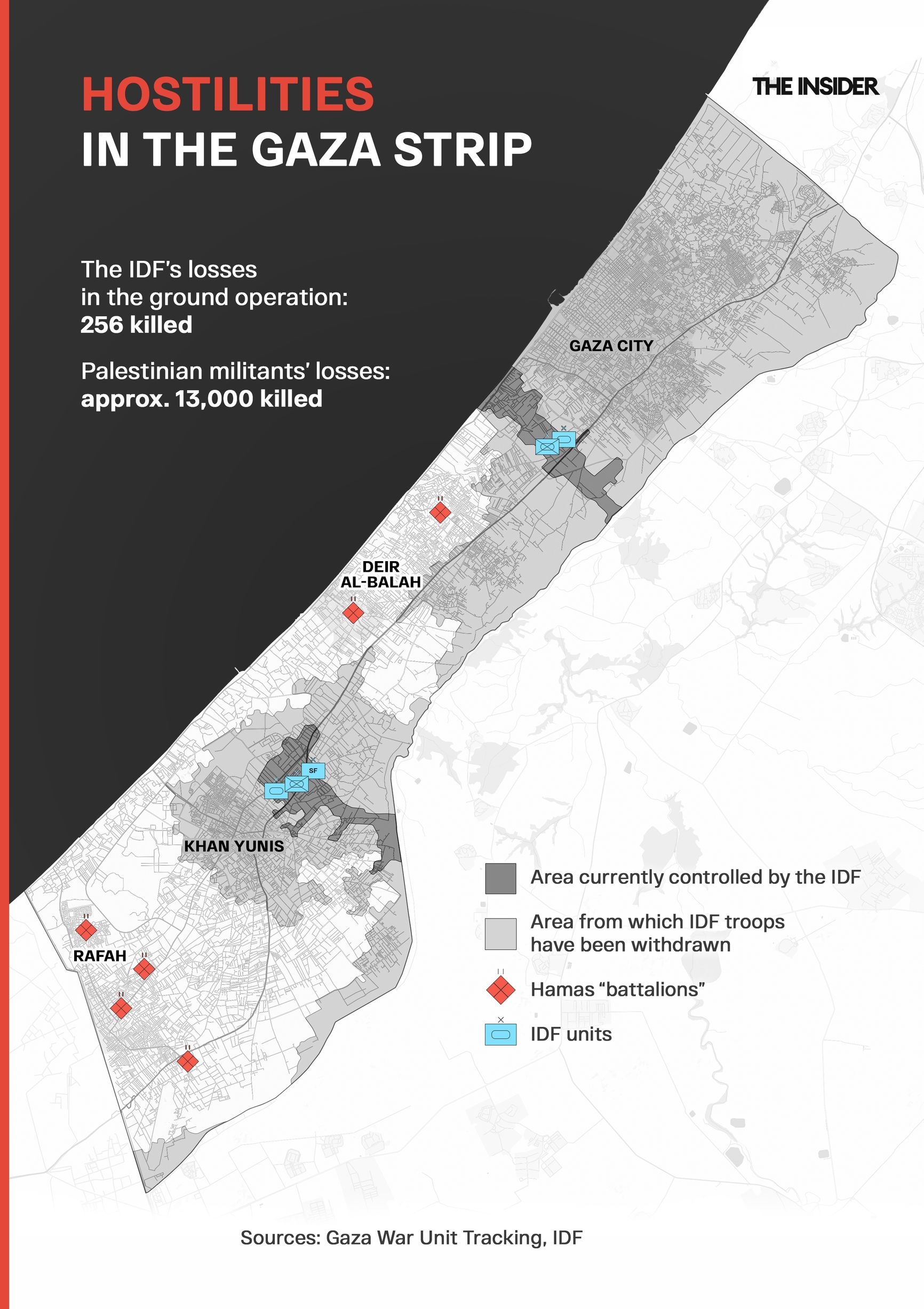

Throughout its Operation Swords of Iron, the IDF has achieved impressive results on the ground. Having lost less than 300 killed and approximately 1,500 wounded since the start of the ground operation in late October 2023, the Israelis claim to have killed 13,000 militants of various Palestinian factions and “defeated” (that is, rendered incapable of combat activity) 18-20 of the 24 so-called “battalions” that belonged to the Hamas movement at the onset of the battle.

In the end, the tunnels proved to be of minimal tactical or operational benefit to Palestinian fighters, save for a few instances of covert movement of forces and ambushes. For example, it was in a tunnel trap that Israeli servicemen Gal Eisenkot, son of cabinet minister and former Chief of the General Staff Gadi Eisenkot, was killed. Presently, ground control and constant aerial reconnaissance allow Israel to immediately detect and eliminate militants in tunnel shafts.

However, the low combat value of the tunnels has done little to bring Israel any closer to a decisive success in the war. Its operations thus far have destroyed most of the housing and infrastructure in the northern part of the sector, meaning that refugees currently located in the south have nowhere to return. Simultaneously, Hamas and its allied groups have demonstrated ruthless survival skills against a numerically and technologically superior adversary. They show no sign of surrendering as the fight moves to yet another dense urban space sitting above yet another vast underground network — and this time, civilians above ground lack a potential safe haven to flee to. Thanks largely to the tunnel network in Rafah, Hamas retains its agency. The group has set conditions for a hostage exchange that are unacceptable to the Israeli government: a permanent ceasefire, withdrawal of all IDF forces from the Gaza Strip, and permission for civilians to return to their places of permanent residence. It appears as if the brutal battle will go forward.

In other words, even after six months of non-stop air strikes, ground sweeps, and sensitive losses in manpower and equipment, the Palestinian militants do not appear desperate to end the fighting. The depth, branching, and technical sophistication of their tunnels, along with the stocks of food and water they contain, have enabled Palestinian forces to remain underground for months, even if they were ultimately driven from their network in northern Gaza. From the Israeli side, the fight for Rafah is unlikely to be any quicker or easier.

Hamas has set conditions for a hostage exchange that are unacceptable to the Israeli government

Tunnels buying time

If nothing else, the tunnel network still under Palestinian militants’ control is likely to keep the current conflict going for an uncomfortably long time. Instead of protecting the lives of the Palestinian people it claims to be defending, Hamas almost celebrates the rising civilian death toll, and the likely brutality of the coming fight is all but certain to work against Israel’s political favor.

Moreover, the IDF retains direct control over relatively small areas in the exclave, and the occasional sightings of militants in areas that were previously cleared by the Israeli forces — particularly at the Al-Shifa hospital — along with regular reports of new tunnels being dug, suggest that Hamas has been able to maintain the functionality of its hidden underground routes despite its loss of the territory above them. For Israel, there is no realistic scenario that would allow its forces to improve the humanitarian situation (a frequent demand of its Western partners) while simultaneously achieving the stated main objectives of the military campaign: the release of all hostages taken during the attack of Oct. 7, 2023, and the destruction of Hamas as a military-political force.

It appears that the “Gaza metro” really is a problem with no clear solution.

Firstly, Hamas leaders are hiding somewhere underground, and are most likely holding the surviving hostages there as human shields.

Secondly, if Israel completely withdraws its troops from the Gaza Strip in the future, no one will be able to prevent militants from rebuilding their underground network, complete with refurbished barracks, warehouses, and places for rocket launchers. Therefore, destroying the environment that would enable Hamas to reproduce its military capabilities — that is, physically securing the underground spaces — is far more important than capturing or killing the group’s current leaders.

Thirdly, since tunnels are not just built under residential and civilian objects, but are directly connected to them with passages, power cables, and utility networks, their elimination is not only a military but also a humanitarian challenge.

What next?

A facility such as an underground tunnel is not easy to locate and inspect, nor to destroy or render unusable. To this end, the IDF employs extremely sophisticated and diverse technical means and methods, from remote-controlled robots to specially trained dogs. It took 30 metric tons of explosives to destroy just one section of a 2.5 km tunnel running between the northern and southern parts of the Gaza Strip.

The effort is spearheaded by the Yahalom special operation forces unit of the IDF’s Combat Engineering Corps and the Oketz canine special forces unit. Israel is known to have attempted to use pumps to flood some of the tunnels with seawater during Operation Atlantis, but the result did not meet expectations. Some of the shafts are being filled with concrete because there are not enough resources to destroy the tunnels entirely.

Israeli and U.S. intelligence sources estimate that, as of January 2024, between 20% and 40% of the Gaza Strip's underground network had been damaged or rendered unusable, although official data on this matter is intentionally concealed. That month, Israeli forces shifted from the maneuvering phase of the war towards a focus on sweeps and individual raids, meaning that the figure is unlikely to have increased dramatically since then.

The IDF may indeed need years to bring the underground tunnels in the Gaza Strip into a state of full disrepair, but there is no telling how much time they actually have, given the growing international pressure to implement a ceasefire before the humanitarian situation around Rafah becomes unmanageable. Some experts doubt Israel’s military objective is at all feasible. Consequently, the strategy of hiding deep underground and emerging victorious when Western politicians force the IDF to withdraw appears to be a practical war plan for Hamas.