Accused of working with the Russian security services, Latvian MEP Tatjana Ždanoka mockingly donned sunglasses at a press conference — as if in a spy movie. The accusations won’t be laughed off that easily: Re:Baltica has obtained almost 19,000 of Ždanoka's e-mails detailing how she served the Kremlin.

By the end of January 2014, Kyiv was simmering with unrest in the wake of President Viktor Yanukovych's about-face on a key issue that helped win him the election four years earlier. Bowing to Kremlin pressure, he’d decided against signing an association agreement with the European Union, a stepping stone for Ukraine’s greater integration with the West. Protestors swarmed and occupied the Maidan, Kyiv’s central square, demanding Yanukovych make good on his promise.

He didn’t.

On 16 January, the president signed a group of laws limiting people’s freedoms to hold protest rallies, thus prompting outpourings of anger that led to the first Ukrainian casualties in clashes with the security police.

On 28 January, the European Parliament (EP) dispatched an emergency fact-finding delegation. Several members of the body met with Yanukovych, Ukrainian opposition groups, and church leaders. Upon their return 48 hours later, on January 30, the delegation briefed their colleagues in Strasbourg, who adopted a resolution calling on the government to stop street repressions and release detained protestors and political prisoners.

Tatjana Ždanoka, an MEP from Latvia, was one of the delegates sent to Kyiv. But she did not report her findings to other legislators from the European Parliament. Instead, she sent a confidential report to her FSB handler Sergey Beltyukov, stating her view that anti-Yanukovych demonstrators, already two months in, were unlikely to disband in the near future. Three days before the trip to Kyiv, Ždanoka traveled to St. Petersburg and met Beltyukov, who had waited for her at the airport.

Ždanoka did not report her findings from Kyiv to other legislators from the European Parliament. Instead, she sent a confidential report to her FSB handler Sergey Beltyukov, saying that anti-Yanukovych demonstrators, already two months in to the Maidan protests, were unlikely to disband in the near future.

“My impressions are contradictory,” Ždanoka wrote to Beltyukov at his burner email account on February 6. “Yanukovych is too cunning to be unraveled in the course of a 1.5-hour conversation. But the feeling is that he is ready for a forceful scenario… On the other hand, some observers are inclined to believe that Yanukovych will sign a treaty with the EU very soon, getting maximum bonuses from all sides. He looked quite cheerful, calm and confident in his meeting with us on Monday. I thought he should have been more confused… [A]s far as the Maidan is concerned — where we walked on Sunday late in the evening, my feelings are mixed: some mixture of farce, drama, horror and comedy (with a preponderance of the third component in this list). It's not going to all dissipate that easily.”

The same day, Beltyukov replied succinctly: “Thank you!!!”

It is not clear what Beltyukov, an officer of Russia’s Federal Security Service (FSB), did with this private intelligence report from a member of the European Parliament (MEP), nor what role it may have played in shaping the Kremlin’s measures in the following days. However, two weeks later the FSB dispatched its own delegation to Kyiv, led by Sergey Beseda, the head of the organization’s Fifth Service, its foreign intelligence arm. Their mission was to pressure Yanukovych not to entertain an accommodation with the protesters, but rather to crack down harder on them. The following evening would see the bloodiest hours of Ukraine’s Euromaidan Revolution, with at least 21 protesters killed by snipers. By the end of February 2014, the embattled Ukrainian president would defect to Russia, and Russia would mount a stealth invasion and seizure of Crimea, kick-starting a war that, through periods of intensification and lulls, continues to the present day.

In January, The Insider, along with its investigative partner Re:Baltica, reported that Ždanoka, whose pro-Russian sentiments were hardly secret to begin with, had been an agent of the FSB for the better part of a decade. Those findings were based on a small tranche of emails of her correspondence with Beltyukov and another FSB handler. In response to our story, the European Parliament opened an inquiry that ultimately led to “sanctions” in the amount of €1,750 to be placed on Ždanoka. Her activities as an MEP were also limited. A Latvian State Security Service (VDD) investigation is ongoing.

The Insider and Re:Baltica can now reveal more of Ždanoka’s connivance with Russian intelligence, based on an even larger tranche of her correspondence with Putin’s spies. Specifically, Ždanoka corresponded with Beltyukov from 2013 until 2017, according to the almost 19,000 emails The Insider and Re:Baltica have examined. She also communicated with another FSB case officer, Dmitry Gladey, her longtime contact and first handler from the Fifth Service.

Ždanoka corresponded with Beltyukov from 2013 until 2017, according to the almost 19,000 emails The Insider and Re:Baltica have examined. She also communicated with another FSB case officer, Dmitry Gladey, her longtime contact and first handler from the Fifth Service.

Among the new findings in this tranche of emails is a message indicating that someone named “Dmitry,” writing from an unknown address ([email protected]), assigned Ždanoka an assistant: Odesa-born student Yulia Satirova. The “group2may” account, which appears to be a reference to the fire that killed 42 pro-Russian demonstrators in Odesa’s trade unions building on May 2, 2014, was used by three different people, none of whom The Insider and Re:Baltica could identify. When asked if “Dmitry” was in fact her handler Gladey, Ždanoka did not respond.

Records show that Satirova did work for the European Parliament between 2015 and 2019, not only for Ždanoka but also for two other politicians: Miroslavs Mitrofanovs, a Latvian parliamentarian and a member of the Latvian Russian Union, Ždanoka’s pro-Kremlin party, and Jiří Maštálka, a Communist MEP from Czechia.

(See The Insider and Re:Baltica’s separate story on Satirova here.)

For the past six months, Ždanoka has denied cooperating with the FSB. She answered questions sent to her for this story on a YouTube livestream but said little about the substance of The Insider and Re:Baltica’s queries — other than to label the new leaked emails as fake. This claim contradicts statements she made after the first investigation about her ties to the FSB, in which she appeared to authenticate the original emails. Ždanoka speculates that it is the writers of this story who are working for the Russian security services, rather than the MEP who spent years actively corresponding with FSB officers.

***

Ždanoka's letters to Beltyukov are short. The tone is businesslike. Both largely used email to arrange meetings, preferring to discuss substantive issues in person. The FSB officer regularly sent warm wishes to Ždanoka on New Year’s and her birthday. When she arrived in St. Petersburg, Beltyukov met her at the airport. He did not forget to flatter her.

In one letter, Beltyukov praised Ždanoka for appearing on Russian state television channels, calling her interventions, presumably about Ukraine, “very important in the current situation.”

In one letter, Beltyukov praised Ždanoka for appearing on Russian state television channels, calling her interventions, presumably about Ukraine, “very important in the current situation.” In exchange for participating in propagandist Vladimir Solovyov’s television program, she was given a car for the day, and an acquaintance booked an appointment for her at a hairdresser.

Ždanoka met Beltyukov in Moscow at a café called Shokoladnitsa in the center of the city, close to Lubyanka, the FSB headquarters.

At the end of 2013, the two met in the Moscow cafe "Shokoladnitsa" near the Lubyanka crossing.

Source: yell.ru

The busiest period of exchanges between the Latvian national and Beltyukov came in 2014, when Russia annexed Crimea and fomented a barely plausibly deniable war in the eastern Ukrainian Donbas region. Almost a decade later, these events would culminate in the full-scale Russian invasion of February 2022.

In late summer 2014, Beltyukov asked whether Ždanoka “could organize an event on a European platform (for example, a photo exhibition) with documentary evidence of war crimes in south-eastern Ukraine. If you have such an idea, I am ready to join you.”

“Of course, Sergei, it is possible,” she replied. “Thank you for your offer to help. But how can I find out more about your assistance?” The question seemed to be about money.

At that time, Ždanoka was preparing to hold a hearing at the European Parliament on the then-recent tragedy in Odesa. In May 2014, a building in which pro-Russian protesters had barricaded themselves caught fire amid clashes with pro-Ukrainian demonstrators. Participants from both sides could be seen throwing Molotov cocktails. In the resulting fire, 42 people were killed, and more than 200 injured. The incident in Odesa is one of the central themes in Kremlin propaganda that attempts to brand all Ukrainian nationalists “fascists” and “Nazis.”

“The date is linked to the events in Odesa, but we will try to draw attention to current events in south-east Ukraine,” Ždanoka assured Beltyukov.

She continued to organize events dedicated to the Odesa tragedy for several years afterward.

At the end of 2014, Beltyukov wrote, “You may soon be contacted by D.G. There is an opportunity to apply for a grant offered through St. Petersburg State University. At first glance, the idea seems interesting.”

Ždanoka replied that D.G. had already called her. She added that, “I look forward to meeting our mutual acquaintance in Riga.”

D.G. is most likely Dmitry Gladey, Ždanoka’s recruiter and first handler in the FSB. The Latvian MEP previously told The Insider and Re:Baltica that he is an old friend with whom Ždanoka took skiing lessons in the Caucasus in the 1970s, back when they were students. They continued to meet in St. Petersburg, where Gladey and his wife lived. They also met in Riga when Gladey's daughter married a Latvian man.

Recently, The Insider revealed that Gladey was a member of the FSB's Fifth Service, the group tasked in 2004 with countering the “color revolutions” that had set Georgia and Ukraine on the path to democracy. The Fifth Service was also responsible for destabilizing Ukraine in advance of the full-scale invasion in 2022.

The Latvian MEP previously told The Insider and Re:Baltica that Dmitry Gladey, now revealed as a member of the FSB's Fifth Service, is an old friend with whom Ždanoka took skiing lessons in the Caucasus in the 1970s, back when they were students.

Re:Baltica has obtained correspondence between Ždanoka and Gladey from 2005 to 2013. The exchanges do not sound like normal chatting between friends. For instance, Ždanoka reported to Gladey about events she had organized, who had been invited, trips she had taken, and observations she had made.

One example is an annual event built around March 16, the calendar date that Latvian nationalists commemorate for legionnaires who were recruited by Nazi Germany to fight against the Soviet Union during World War II. During their annual march to lay flowers at the Freedom monument in Latvia's capital, pro-Russian activists who call themselves “anti-fascists” always try to stage a protest.

In 2005, Ždanoka organized provocations at these events in order to “prove” to her colleagues in Europe that Latvia still harbors Nazi sympathies. That year “anti-fascists” dressed up as Jewish concentration camp inmates — replete with yellow stars on their chests — attended the festivities, providing ready-made material for Russia’s TV channels.

"Anti-fascists” dressed up as Jewish concentration camp inmates — replete with yellow stars on their chests — attended the Remembrance Day of the Latvian Legionnaires in Riga on March 16, 2005.

Source: LETA

Demonstrators dressed up as Jewish concentration camp inmates wrestle with Latvian police officers. Riga, March 16, 2005.

Source: LETA

Gladey’s questions indicate he was aware of the plans before the protest took place. Ždanoka was to organize the confrontations, photograph them, and send news to her colleagues in the European Parliament centered on the claim that Nazis were now marching in Latvia’s capital.

“I hope you managed to get some rest?” Gladey messaged his agent. “I look forward to the promised updates on the March 16th article - the text of your statement, the reactions of MEPs, and the consequences.”

“We had a good rest, but also had an adventure,” Ždanoka replied. “I'm sending the text and accompanying photos. The first short text explaining the photo was sent on March 16th to the Greens (53 people) in my group. A longer text was sent on March 17th to the same Greens and another group on minority issues (42 people). We will get the full reaction of MEPs next week.” Until April 2022, Ždanoka was a member of the Greens/European Free Alliance group in the European Parliament.

Her letter was indeed accompanied by photographs from the march showing Ždanoka’s costumed supporters being detained by Latvian authorities. One picture showed swastika-adorned posters littering the ground. Only a single photo shows the actual Legionnaires in attendance — old men standing calmly with flowers in their hands.

Ždanoka also forwarded Gladey a statement she’d sent to her fellow members of the European Parliament. In it, “the MEP expresses her outrage” at the violence used by the police “against anti-fascist protesters.” The attachments also included a reaction from other Latvian MEPs calling Ždanoka's release a “masterpiece of demagoguery.”

***

In September 2013, Moldova, one of the poorest countries in Eastern Europe, received a severe economic blow when Russia banned the import of its wines, allegedly over insufficient quality control. In reality, Russia was using economic pressure to prevent the signing of a cooperation agreement between Moldova and the EU at the Eastern European Partnership Summit in Vilnius a month later.

The context for these developments dates back to 2009, when the EU established the Eastern Partnership (EaP) to bring the countries on its eastern border out of Russia's orbit. Moscow used everything in its arsenal to stop the initiative, including trade restrictions, information warfare, and a ban on natural gas supplies.

As an MEP, Ždanoka regularly traveled to the EaP countries and reported her observations to Gladey. The FSB, therefore, had a well-placed spy at several critical European meetings, particularly those that concerned the potential Western accession of countries within the Kremlin’s self-proclaimed “near abroad.”

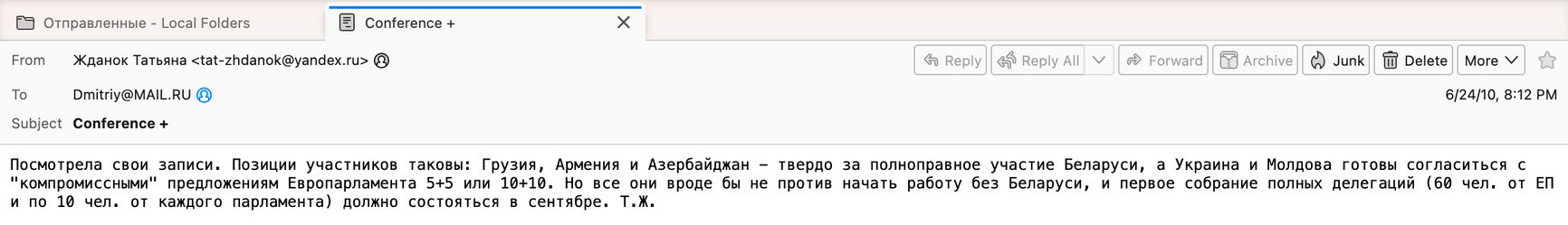

In the summer of 2010, Ždanoka first sent Gladey a program for the visit of deputies from potential EaP countries to Brussels. Later, she reported back on which participant countries were — and were not — in favor of including Russian ally Belarus in the project.

A screenshot of Ždanoka's email to Gladey dated June 24, 2010.

“I checked my notes,” she wrote to Gladey on June 24, 2010. “Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan strongly favor full Belarusian membership, while Ukraine and Moldova are ready to accept the 'compromises' offered by the European Parliament… But all of them are apparently not opposed to starting work without Belarus.”

A few months later, Ždanoka and other MEPs went to Moldova. In the report to Gladey, she summarized who was present, what was said, and the relationship between various politicians.

Ždanoka mentioned that a lunch was planned by Moldova’s then-President Mihai Ghimpu, who did not turn up due to illness. The president was represented by a deputy with a “thinly disguised dislike” for Ghimpu. “He joked that his illness was a consequence of the wine festival at the weekend.”

In 2012, Ždanoka traveled to Azerbaijan. Before such visits, MEPs are provided with thick folders containing analyses of the host country's economy and politics, CVs of senior officials, information on support from international funds, and briefings on key issues — such as the suppression of protest movements. Ždanoka forwarded the nearly 70-page report to Gladey. These documents were not confidential, but they were sensitive and intended only for MEP delegations, not the general public, much less Russian intelligence.

Then came the climax.

In Vilnius in November 2013, the EU planned to sign cooperation agreements with several Eastern Partnership countries, and Russia was increasing the pressure. Wine imports from Moldova and chocolate from Ukraine had been banned. Moscow also threatened to cut off gas supplies, a serious contingency given the approaching winter.

The MEPs who gathered in the Lithuanian capital agreed to adopt a resolution condemning Russia's strongarm tactics. Ždanoka sent this resolution, too, to her FSB case officer.

“In the meantime, I am sending the draft resolution prepared by the Greens. I can’t access the other groups' drafts, but you can get an idea from this one. Tomorrow, a compromise will be discussed and agreed upon with several groups. The debate will take place on Wednesday, and the vote on Thursday.”

Two days later, Ždanoka sent the final version of the resolution and the text of her speech to Gladey. In it, she acknowledged that Russia was exerting pressure, but pointed to the EU’s alleged duplicity: Moldova would no longer be able to export wine to Russia, but the EU offered no alternative market. She used Latvia as an example, saying that it had joined the EU, but “the marriage was not equal.”

In essence, Ždanoka repurposed for Moldova a message the Kremlin had been spreading in the Baltics for years: the EU is treating you unjustly, and if you stay with Russia, your country will be better off.

In essence, Ždanoka repurposed for Moldova a message the Kremlin had been spreading in the Baltics for years: the EU is treating you unjustly, and if you stay with Russia, your country will be better off.

“I am shocked,” the former German MEP Rebecca Harms, then leader of Ždanoka's EP group, told The Insider and Re:Baltica after learning of the emails. “It makes clear that she had not only ‘another opinion’ on Russia-related issues but was really an informant. I really regret that I was not strong enough to organize a majority to expel her from the Green group.”

A Western intelligence officer told The Insider, “The FSB’s Fifth Service is responsible for operations abroad and some of their preferred methods is to recruit or cultivate agents in politics. The goal is not only to collect information but also influence the society and thus decision makers regarding Russian foreign policy.”

***

Ždanoka didn’t just report on contemporaneous events. She also offered helpful advice to Russian intelligence on how it could be more effective in meddling in European political affairs.

In an October 1, 2009 email, Ždanoka sent Gladey “an analysis of the errors in the work of some structures that affect Russia's image abroad.”

She pointed out that Russian diplomats abroad were ill-prepared to work with the media and were easily “outflanked” by their Baltic and Georgian colleagues, who were “young, dynamic [and] trained in the West and fluent in foreign languages.”

Ždanoka noted that this dynamic was clearly visible during Estonia’s 2007 “Bronze Soldier” episode concerning Tallinn’s removal of a Soviet World War II monument from a busy city intersection to a military cemetery. The relocation was met with Russian-stoked riots and a crippling nationwide cyberattack later linked to Russian hackers. Another example Ždanoka cited was connected with the 2008 Russo-Georgian war, in which Moscow’s diplomatic chicanery proved incapable of convincing the wider world that Russia was anything other than the aggressor.

In her written analysis, Ždanoka was also critical of Russian officials who treated foreign trips as tourist adventures, noting that Moscow’s envoys too often compensated for their lack of credible arguments by adopting an “arrogant attitude” she summarized as: “Russia has gas and oil, so you have to respect us.”

Ždanoka proposed the creation of a special ministry to promote Russia's image abroad, taking the example of the Latvian Institute, which is mainly staffed by Latvians with foreign roots. “They know how to talk to foreigners,” she wrote. At the same time, she lobbied for her own activities and mentioned that personnel for the proposed new ministry could be recruited at the European Russian Forum (ERF) she was organizing.

For several years, the ERF was Ždanoka's most important event in Brussels. She booked the venue in the European Parliament building almost six months in advance and took on the role of hostess, with important Russian officials sitting at her side. Among the Forum's founding members were representatives from the Moscow Mayor's Office, the Russian Orthodox Church, and Ždanoka's political group in the parliament. Funders included the Russian Foreign Ministry and the Russkiy Mir (Russian World) Foundation.

The forum, along with a series of discussions and exhibitions, allowed Ždanoka to bring a number of questionable people into the European Parliament: Russian politicians, some of whom are currently on sanctions lists; agents of influence who have subsequently been tried for espionage; and some additional figures with links to the Russian security services.

Through these soft power activities, Ždanoka helped whitewash Russia in the minds of some MEPs while creating content for Kremlin TV channels. The main message was that the EU cannot do without Russia and must make friends.

“What is typical of her and a number of other MPs who work in that pro-Russian style is that the Moscow media exploits it,” Latvian MEP Sandra Kalniete told Re:Baltica. “It is all filmed.”

Still, Kalniete and other current and former MEPs interviewed by Re:Baltica believe that Ždanoka’s political influence in the EP was marginal. “Expanding the European Russian Forum was the key,” another long-term Latvian MEP, Roberts Zīle, said. “To bring the concept of the Russian world to the West.”

***

After her election to the EP, Ždanoka started actively renovating her family home in Valdai, Russia, a popular holiday destination. The photos show how the sad-looking one-story house with an attic slowly came to life with new dark green wooden walls and white window frames. Ždanoka sent the builders a kitchen plan and decided where to put the appliances. It is not clear from the emails whether anyone lives there, but it is implied that relatives live nearby.

Ždanoka's family house in Valdai, a favourite place for holidaymakers. Before and after the renovation, which, as we can see from the emails, was paid for by the MEP.

Source: Ždanoka's emails

Ždanoka's family house in Valdai, a favourite place for holidaymakers. Before and after the renovation, which, as we can see from the emails, was paid for by the MEP.

Source: Ždanoka's emails

Ždanoka's family house in Valdai, a favourite place for holidaymakers. Before and after the renovation, which, as we can see from the emails, was paid for by the MEP.

Source: Ždanoka's emails

Ždanoka will no longer be part of the new EP, as the Latvian parliament passed a law preventing her from standing due to her communist past. She has served 20 years in the European Parliament.

After Re:Baltica and its partners published information about her cooperation with Russian special services in January of this year, Latvia's security service (VDD) initiated a probe but declined to comment on the findings for this article. The European Parliament's inquiry resulted in a fine of €1,750 and a ban on representing the EP in foreign visits and other events. Ždanoka claims it was a punishment for mistakes in official declarations.

In her YouTube address devoted to The Insider and Re:Baltica's questions, Ždanoka showed colorful brochures listing the participants of events she has organized. It’s all been transparent, she insisted. The Russian Foreign Ministry is listed as one of the co-financiers of the events. The rest of the funding, as with her trips to Russian-backed Syria and Russian-occupied Crimea, was covered by the European Parliament — that is, the taxpayers of the European Union.

In response to the accusations against her, Ždanoka called herself “an agent of peace.”

Asked whether she intends to move to Russia after her career is over, she snapped: “I am not going to move to Russia. Where you were born, there you are useful. I was born in Riga.”

With contributions from Sanita Jemberga, and the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP).