Russia's armed forces entered Vladimir Putin’s full-scale war against Ukraine with a relatively small but nominally professional force. Two years later, the image of the army has drastically changed. Mobilized soldiers, mercenaries, and prisoners have been added to its ranks. The level of training has taken a serious hit. Corporal punishment and illegal detention have become the norm. And medical care has been reduced to a minimum — in many cases deliberately. 97% of the wounded who survive and make it to the hospital are sent back to the front. The supply of new equipment, on the other hand, is less reliable.

Content

“A rabble of cons, drug addicts, and looters”

Golf carts instead of Armata tanks

Meat grinder assaults and wave attacks

Cellars and torture instead of courts-martial

97 wounded out of 100 return to service

A “quiet war” on civilians

“A rabble of cons, drug addicts, and looters”

The changing composition of the Russian army over more than two years of the war is evident from a monthly graph of military losses compiled by the BBC Russian Service. In the summer of 2022, Russia’s first so-called “volunteer units” joined contract soldiers. In the fall, “temporary” mobilization saw new draftees, along with convicts, join the mix. In early 2023, a new wave of mercenaries — effectively new contract soldiers, whose recruitment is still ongoing — was added. The old units, once composed of contractor professionals, have since been significantly diluted by mobilized and “volunteer” personnel. A typical example is the 155th Naval Infantry Brigade, which already had a significant number of mobilized soldiers, along with representatives of other naval specialties transferred to the Naval Infantry, during the failed Vuhledar offensive in the winter of 2022/2023.

“Tasty gifts” (dried bread rusks) handed to Russian army units in occupied Donbas by volunteers

“Tasty gifts” (dried bread rusks) handed to Russian army units in occupied Donbas by volunteers

In percentage terms, according to the calculations of Russian independent online outlet Mediazona and the BBC’s Russian Service, most of the Russian casualties are still prisoners whose lives and limbs were spent for the sake of the Bakhmut meat grinder. However, at that time convicts were fighting as part of the Wagner Private Military Company (PMC). Later, the Russian Defense Ministry took over the recruitment of prisoners from Wagner’s handler Yevgeny Prigozhin while the fighting for Bakhmut was still ongoing. Detachments of prisoners, called “Storm Z” or “Storm V,” are now used as expendable infantry — as noted by the UK’s Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) in a report last year. Their task is to identify weaknesses in the enemy's defenses at great human cost, making the ultimate attack less bloody for the Russian military’s better-trained personnel. Even propagandists admit that only a small percentage of prisoners return from the assault units, and that those who are fortunate enough to survive face problems with pay, disability, treatment, and rehabilitation.

“Storm Z” / “Storm V” personnel: Dmitry Malyshev, sentenced to 25 years in 2015 for murdering a man and filming himself eating the victim’s heart, takes a selfie with Alexander Maslennikov, who got 23 years for murdering and dismembering two women he met at a nightclub

Photo: Bloknot Volgograd

A special case involves those units whose members can better be described as mercenaries, rather than as regular soldiers. According to investigative journalists, fighters for these formations are recruited through the so-called “Redut” PMC, which in fact is simply a front for structures connected with the GRU — Russia’s military intelligence agency. Members of some of these semi-regular units profess far-right and openly neo-Nazi views. Examples include the Española unit (formed by soccer hooligans) and the “Rusich” Sabotage Assault Reconnaissance Group (DShRG). Representatives of the latter openly call for the killing and mistreatment of Ukrainian prisoners of war.

A special case involves those units whose members can better be described as mercenaries, rather than as regular soldiers. According to investigative journalists, fighters for these formations are recruited through the so-called “Redut” PMC, which in fact is simply a front for structures connected with the GRU — Russia’s military intelligence agency. Members of some of these semi-regular units profess far-right and openly neo-Nazi views. Examples include the Española unit (formed by soccer hooligans) and the “Rusich” Sabotage Assault Reconnaissance Group (DShRG). Representatives of the latter openly call for the killing and mistreatment of Ukrainian prisoners of war.

Members of some detachments recruited through PMC Redut share neo-Nazi views

The so-called “Veterans” (“Veterany”) PMC, which was personally praised by Putin, deserves particular mention. Far from echoing the Russian president’s praises, a mobilized serviceman of the 1487 Regiment described the unit as “a rabble of ex-cons, drug addicts and looters.” The “Veterans” were also accused of buying mobilized personnel for 25,000 rubles ($275) per head — and then sending them on suicide missions at the front lines in Ukraine.

A photo from the Telegram channel of the “Rusich” Sabotage Assault Reconnaissance Group (DShRG), likely showing the torture of an unidentified person

Source: DShRG “Rusich”

Another source of replenishment of Russian troops involves the recruitment of foreign citizens. Often enough, foreigners find themselves in the Russian Armed Forces after receiving promises of work on Russian territory from one of a wide network of recruiters. Once at the front, these unintentional Russian assault troops experience the worst of what the Russian military has to offer its fighters.

Mediazona found in statistics from the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs indicating that the year 2023 had seen a record number of visas issued to Nepalese citizens — around three thousand. In February of this year, CNN reported that Russia had recruited up to 15 thousand Nepalese for the war with Ukraine. In addition, the mass recruitment of citizens of Sri Lanka and India into the Russian Armed Forces has also become known.

Golf carts instead of Armata tanks

Over more than two years of Russia’s full-scale assault on Ukraine, the invaders’ military-industrial complex has seriously expanded the production of major types of weapons and military equipment — at least if official figures are to be believed — and Western intelligence agencies appear to believe at least some of them. For example, a CNN source spoke of the delivery of 1,500 tanks per year, while Russian ex-Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu reported a similar figure — 1,530 tanks. However, the same American source rightly noted that most of the Russian equipment making its way to the battlefield is not new, but has either been modernized or was simply taken out of storage. At the same time, Russia’s most modern equipment, such as the T-14 Armata tank, is not used in Ukraine due to the small number and high cost of such pieces of equipment in the Russian arsenal.

In practice, the Russian Armed Forces rely on increasingly obsolete equipment. Its losses of more modern tanks and IFVs during the fighting for Avdiivka this past winter were relatively small, while Soviet-era models accounted for most of the destroyed, damaged, and abandoned equipment. Last year, The Insider reported on the appearance of such long-retired tank models as the T-55 and T-62, along with BTR-50 armored personnel carriers (APCs) among the Russian Army’s mechanized ranks. This antique equipment was used by Russia’s 21st century military in assault operations during the battle of Avdiivka (1, 2, 3).

In some cases, old tanks are used not for their intended purpose, but as “infantry taxis” on the battlefield. In order to protect these vehicles, they are modified with additional defenses that transform them into monstrous structures known as “tsar mangals” — literally “king of grills” — or, in Western parlance, as “turtle tanks,” The practice of sending infantry into battle riding atop tanks hearkens back to World War II, when Soviet industry did not produce any armored personnel carriers, and supplies of such vehicles under the Lend-Lease program were scarce.

At the same time, the huge number of Russian vehicles destroyed looks relatively small compared with Moscow’s many thousands of personnel losses. In practice, the level of the Russian Army’s mechanization seems to be slipping back to the 1940s, when infantry units without armored vehicles were the backbone of the Red Army.

In addition to obsolete equipment, vehicles not designed for the battlefield are used in combat. In particular, the Russian infantry moves on lightly armored tracked MT-LBs — not only behind the front line, but also right on the line of contact. These vehicles are modified to transport infantry by enlarging the cargo hold. The scale of their use is demonstrated by the fact that during the Avdiivka offensive, the confirmed losses of Russian MT-LBs exceeded 100 units (while the total confirmed losses of armored fighting vehicles during the battle reached 690).

There have also been repeated (1, 2, 3) cases of Russian attacks using Chinese-made Desertcross all-terrain vehicles (ATVs), with Ukrainian soldiers nicknaming the vehicles “golf carts” — as they seem unmistakably out of place on the battlefield. This type of equipment is characterized not only by its reportedly inflated procurement price, but also by a complete lack of protection for the ATV’s crew. It can be assumed that the Russian military is hoping to use the speed of these vehicles in order to slip through the kill zone of FPV (first-person-view) kamikaze drones and artillery. Judging by the number of casualties, however, this isn’t always possible.

The Russian situation with infantry weapons is not good either. Analyzing one of the failed Russian attacks west of Avdiivka, Russian serviceman Svyatoslav Golikov noted that most likely the attackers simply lacked infantry anti-tank weapons, which is why they were unable to fight back against Ukrainian Bradley IFVs. As for small arms, Mosin-Nagant rifles, which were the main Russian and Soviet infantry weapon during both world wars and were distributed in 2022 during the mobilization in occupied Donbas, are still used on the front (though it's worth noting that they are most often used by snipers). Troops are also supplied with the obsolete Maxim, DP-27 and RP-46 machine guns, which, as noted by military blogger Rostislav Mokrenko, require crews from 2 to 6 people for their effective use.

Meat grinder assaults and wave attacks

The Russian Army has improved its tactics somewhat in recent years. This is particularly evident in the successful repulsion of the Ukrainian counteroffensive in 2023, the increased use of UAVs to guide artillery fire, and the recent defeat of key targets such as HIMARS MLRS and Patriot SAMs with precision weapons. At the same time, the Russian Armed Forces remain incapable of putting together an effective offensive, as they suffer heavy casualties in their attempts to capture relatively small population centers — this despite their superiority in manpower and ammunition.

According to the BBC Russian Service, the dynamics of the current losses are comparable to the figures observed during last year's winter offensive in Donbas. The publication explains the high figures as being the result of wave attacks (the successive introduction of small groups of infantry into battle) similar to the tactics used by the Wagner PMC in the battles for Bakhmut more than one year ago. The Ukrainian OSINT project DeepState also reported on these tactics, noting that they have on occasion brought the Russians some success. According to DeepState’s authors, logistical routes are first shelled with artillery and FPV drones, and then small groups of infantry are sent into battle to identify and suppress Ukrainian firing positions. Losses in the first waves can reach 95%. After suppressing the firing positions — a process that can include the use of guided aerial bombs — “experienced assault units” are introduced into the fight.

In many cases, the cause of casualties seems to be not so much wasteful tactics as a simple lack of preparation. For example, the self-styled Russian “war correspondent” Yuri Kotenok, speaking about another destruction of Russian assault groups in the village of Berdychi near Avdiivka, claimed that there were “meat [grinder] assaults without normal training, without taking into account even the basics of tactical actions of this kind.” Kotenok also reported on the Russians’ lack of reconnaissance and fire support:

“We see the complete incompetence of the command at company-battalion level and a lack of elementary understanding of [how to] attack at the squad level. The soldiers clearly lack training.”

The political demand for constant offensive actions results in a vicious circle. The mass deaths of soldiers in poorly organized attacks compel the Russian military to resort to the use of “new contract soldiers,” who have not had time to undergo training in offensive tactics. A Russian serviceman wrote that during the fighting for Avdiivka, two to three weeks of training was the (positive) exception rather than the rule. A post from the Ukrainian 47th Mechanized Brigade, published on March 11, claims that according to the documents of Russian soldiers who died in yet another assault, some of them had joined the army on March 5 — less than a week before their deaths. The fact that many recruits are older and have low morale only makes the situation worse.

Some Russians who died in yet another assault had joined the army a few days earlier

Cellars and torture instead of courts-martial

What makes soldiers commit to suicidal frontal assaults instead of disobeying orders and going to jail? The most likely reason is that soldiers at the front can't expect to be investigated and tried according to the law. Instead, when located on the occupied territories of Ukraine, they are subjected to an informal system of punishment that takes the form of unlawful detentions, beatings, and other forms of abuse in order to bring the fighters back to the front.

One of the most widely publicized examples of such abuse that has come to light in recent months is an article by journalist Olesya Gerasimenko in the independent Russian publication Verstka. That story described violence — including sexualized violence and torture (such as being handcuffed to a tree in the cold) for drunkenness, indiscipline, and refusal to go to the front lines. According to the soldiers themselves, it is impossible to obtain due process. One officer explains the situation as follows:

“We don't just f**k up anyone. There are a lot of [mobilized soldiers] here, men who have recently signed a contract [...] before this, they could be found getting wasted in garages, along with other types. Do they have discipline? No. To keep discipline, you gotta beat 'em up hard. You can call it bullying, but it's our job, our lives depend on it. [...]

There ain't enough military police to clean this sh*t up. If you don't join an assault, you end up in a basement. [This system] works.”

The practices described are not new, and some of them are quite organized. Since 2022, the Russian publication Astra has reported on a facility in Zaitseve, Luhansk Oblast, which hosts an unofficial detention center for army “refuseniks” from all along the front. Evidence of even harsher disciplinary methods — extrajudicial executions practiced in the ranks of the Wagner PMC, for example — have also appeared. After Yevgeny Prigozhin's death and the dissolution of his Wagner Group, the practice of such harsh treatment seems to have disappeared — at least, there is no reliable evidence in open sources indicating the deliberate killing of Russian servicemen for disciplinary purposes.

However, it has also been reported that these punishments have ended up with soldiers tortured and beaten to death (1, 2, 3).

97 wounded out of 100 return to service

According to repeatedly (1, 2) announced Russian MoD data, more than 97% of wounded servicemen return to service. The figures seem are incomparable to any other military: for example, among the U.S. military in Iraq, a conflict of much lower intensity than the Russian-Ukrainian war, the total percentage of surviving wounded soldiers in the first four years of the conflict was 90.4% — and the percentage of those who returned to the battlefield was of course something below that.

A wounded Russian serviceman with an Esmarch bandage, which was invented at the end of the 19th century

Source: ДвiЩ

If the Russian figures aren’t outright lies, we can assume that two factors are responsible for those numbers: the first is the difficulty and poor availability of casualty evacuation, which means that a large proportion of seriously wounded soldiers simply don’t make it to the hospital; the second is the command’s desire to return soldiers to the front lines regardless of their condition.

Even if the medical evacuation system worked perfectly, it would be hampered by an abundance of drones capable of correcting fire along logistical routes and attacking evacuation teams on their own. According to the Conflict Intelligence Team, these attacks, which constitute war crimes, are widespread on both sides of the conflict. At the same time, a Russian serviceman quoted earlier notes that special “evacuation” groups are a tactical innovation that only appeared during the fighting for Avdiivka. According to him, guaranteed — but not always timely — casualty evacuation is provided only for “specialists”: drivers and operators of UAVs, ATGMs, artillery, mortars, and communications systems.

Russia only provides guaranteed casualty evacuation to wounded “specialists” — not to all military personnel

The designation of “specialists” as a separate subclass of infantry was noted in the aforementioned a Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) report from a year and a half ago. Ordinary wounded soldiers sometimes have to wait more than a week to be evacuated from the front line. Aside from that, evacuation transports can also be hijacked by friendlies — other Russian units.

Those servicemen who do manage to get to the hospital face a new problem: they are compelled to get back to the front as soon as possible — by any available means. There are stories of soldiers being sent to the front lines with shrapnel in their hips, concussions and PTSD, and without fingers on their hands. Here’s how human rights activists explain these practices:

“Medical-military commissions, if they are held, are carried out with gross violations. They overestimate the eligibility groups in order to send as many people as possible back [to war]. This is a widespread practice.”

Russia has gone so far as to create entire “disabled” assault units, made up of fighters with serious health problems. This can be partly explained by the lack of hospital space, as evidenced, for example, by the conversion of the Rostov maternity hospital into a military facility — by evicting women in labor.

A “quiet war” on civilians

The vast majority of known cases of Russian soldiers’ crimes against civilians, as well as looting, date back to the spring of 2022. International organizations and law enforcement agencies managed to collect the necessary data after Ukraine liberated multiple settlements in the north and east of the country. In the occupied territories, repressions are now mostly carried out by the Russia-installed police force and the FSB, Russia’s state security service. Data on torture, murder, and looting by Russian security forces in such areas is also regularly leaked.

Igor Pimenov, a policeman from the Moscow Region sent to Kherson Oblast, confessed that in November 2023 he and four colleagues tortured local resident Ruslan Rusnak to death. Also in Kherson Oblast, servicemen beat, robbed, and electrocuted a Ukrainian man, demanding that he tell them where he was apparently hiding machine guns and grenades. In another case in Jan. 2024, Russian soldiers shot a family in occupied Kreminna.

In April 2024, two previously convicted Russian soldiers unleashed a massacre in the villages of Abrykosivka and Podo-Kalynivka, killing seven people, including several fellow soldiers, and setting fire to two houses. These cases are only reported by anonymous sources, who may not have the full picture of the Russian army’s crimes against civilians.

Persecution of the local population is also carried out at the official level. The Russia-installed “governor” of the Zaporizhzhia Oblast, Yevgeny Balitsky, openly spoke about the deportations of local residents who spoke out against the occupation, and referenced “extremely harsh” decisions taken against dissenters, although he failed to specify what the nature of those decisions was.

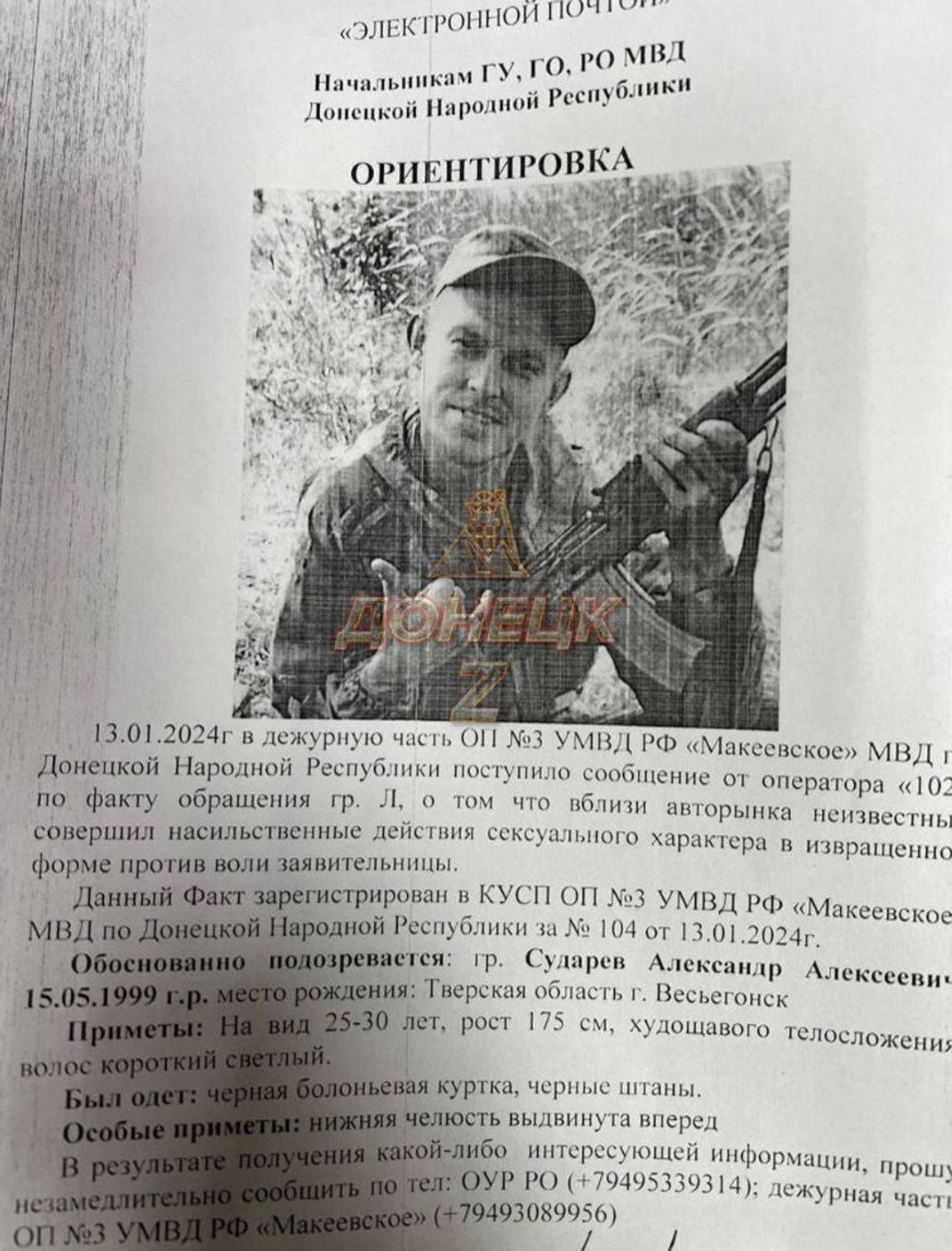

An APB on one of the Russian soldiers distributed in the Donbas; the “authorities” are looking to detain the man on suspicion of sexually assaulting a woman

Source: Donbas Z (Telegram)

Incidents of looting also appear to be ongoing, even if they are limited by the fact that the Russian army now captures much smaller areas than it did in the early months of its full-scale invasion. For example, a video from occupied Avdiivka recently surfaced online showing a Russian military officer who says that the surviving houses “have everything,” and that it would take a “freight train” to transport all the loot back to Russia.

In another video, a Russian military officer laments that he can't get to a TV in a destroyed house, then examines the abandoned apartment and decides to take an entire bed for himself. Another video shows Russian servicemen discussing colleagues who take carpets and sofas from the local population back to their dugouts.

Finally, a video from Zaliznyi Port in Kherson Oblast depicted the looting process itself. In this episode, Russian servicemen were seen pulling wires from household appliances from an abandoned house — seemingly for their own use. Some reports suggest that Russian law enforcement agencies have begun to crack down on looting, but it is unclear how successful they have been.

In any case, the “new look” of the Russian army differs significantly from the image presented by Kremlin propaganda. Problems with personnel, equipment, quality of training, morale, discipline and medical care obviously limit the offensive capabilities of the Russian army in Ukraine. So far, this has not prevented it from continuing its offensive, but it has significantly reduced its pace.

RUSI analyst Dr. Jack Walting believes that the Russian army will reach the peak of its capabilities by the end of 2024 and is unlikely to achieve major successes in 2025 and later. Under these circumstances, foreign support for Ukraine is crucial in order for it to survive this critical period.