The Insider, Re:Baltica and Delfi report on Latvian and Estonian court documents showing how the GRU is recruiting Baltic citizens to vandalize and set fire to targets in the West.

In May 2022, a homeowner from the small village of Rembate, an hour's drive from the Latvian capital Riga, was working in her garden when she saw a black car turn into her driveway. A young man got out. By the time the homeowner reached the gate, the car had driven off, leaving a folded piece of paper on the ground. She picked it up but quickly forgot about it, distracted by the newspapers the mailman had just delivered.

The next day, upon reading the note, she immediately handed it over to her son-in-law, who works in the Latvian Armed Forces. He informed his superior, who then contacted the Military Intelligence and Security Service. The next day, an investigator turned up at the woman’s house.

The swift response was due to the note’s heading: “Mission, Lielvārde Military Airfield.” Below were instructions on what to photograph at the airfield and how to respond if questioned about the reasons for taking pictures. The back of the note featured a childlike drawing of an airplane.

The house where this document was found is located just a few kilometers from the Lielvārde base, which houses Latvian military aircraft — including U.S.-supplied Black Hawk helicopters — used for continuous surveillance of Baltic airspace.

Black Hawk helicopters at Lielvārde airbase

Photo: Latvian Ministry of Defense

As such, even locals around Lielvārde proceed cautiously. “We should be careful even when going to pick mushrooms because we are so close to a military facility,” the homeowner, who asked that her name not be used, told The Insider. “At any moment, someone can ask us to show documents.”

It bore all the hallmarks of a standard intelligence tasking given by a handler to an agent, which is what it was. Thanks to the note’s discovery, Latvian authorities were able to track down a network of saboteurs recruited by the Russian special services. Relying on Latvian citizens, the network consists of operatives who have been dispatched to several countries on paid missions of subversion and provocation, all aimed at undermining Western support for Ukraine. Remarkably, this team was even assigned to burn down a military facility in Kyiv in January 2022, just a month before Russia’s full-scale invasion.

“The goal already then was to instill fear among Ukrainian residents,” Normunds Mežviets, head of the State Security Service (VDD), told The Insider. “Just as Russia is now trying to do in Europe with acts of sabotage.”

Indeed, such acts have grown exponentially throughout NATO countries in the last two years, coinciding with Russia’s faltering campaign on the battlefield. The efforts are part of what Estonia’s Prime Minister Kaja Kallas has dubbed the Kremlin’s “shadow war” against the West, whose resolve and determination in arming and supporting Kyiv has further contributed to Russian military setbacks.

The sabotage operations are so numerous and widespread that a new one is uncovered and reported on every week or two. Plots have included arson attacks on a large-scale shopping mall in Warsaw, an IKEA warehouse in Vilnius, a museum in Riga, a bus depot in Prague, an industrial estate in east London, and a metals factory in Berlin owned by a company that makes air defense systems. In the last two instances, the sites have been linked to military aid bound for Ukraine.

In total, at least eight serious Russia-linked incidents have been reported in Poland and the Baltic states alone. According to Western intelligence services, this continent-wide campaign is being led by the GRU, Russia’s military spy agency.

Owing to Europe’s mass expulsion of Russian diplomats — many of them intelligence officers — following the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, local recruitment efforts have increasingly given way to the virtual variety. The GRU selects its assets via social media platforms such as Telegram and instructs them to carry out everything from vandalism to terrorism to undermine Western support for Ukraine. The paydays range from between a few hundred and thousands of euros, often transmitted in cryptocurrency.

In a joint investigation, The Insider and Re:Baltica, relying on exclusively obtained court documents and CCTV footage, can reveal how the GRU’s recruitment process works and who the individuals who agree to work for Russia are.

***

The note found by the owner of the house in Rembate was like hitting the jackpot for the authorities. It had everything: detailed instructions and meticulously recorded expenses.

At the bottom of the page, it read: “Create a report on the criteria! 1. Transport 2. Perimeter 3. Rest points 4. Location for all photos!”

Next to it were the costs for two nights at a guesthouse near the airfield and the rental of a Canon camera.

First, investigators visited the guesthouse near the airfield. The owners remembered that they had only one guest that night: a young, tall man named Sergejs. His hair was in a ponytail and he wore a t-shirt and ripped jeans. Sergejs spoke Latvian and paid in cash.

He had come to relax with his guitar and Canon camera, or so it seemed to his hosts. He said his boss had treated him to a holiday for a job well done. He mentioned working in a shopping center in the Latvian capital, Riga. Sergejs also inquired about where the soldiers from the airfield go to unwind. The owners recommended a café, Kante, in the nearby town.

S. Hodonovičs wrote the received instructions on a piece of paper, which he later lost. It turned out to be a big mistake

Source: Criminal case materials

S. Hodonovičs wrote the received instructions on a piece of paper, which he later lost. It turned out to be a big mistake

Source: Criminal case materials

Sergejs had arrived at the guesthouse in a CarGuru vehicle, so the next stop for the investigators was the rental agency. Using the GPS data from the car, they traced Sergejs’s route but could not yet crack his identity as the car had been rented under a woman's name — no doubt under the careful instructions of his handlers.

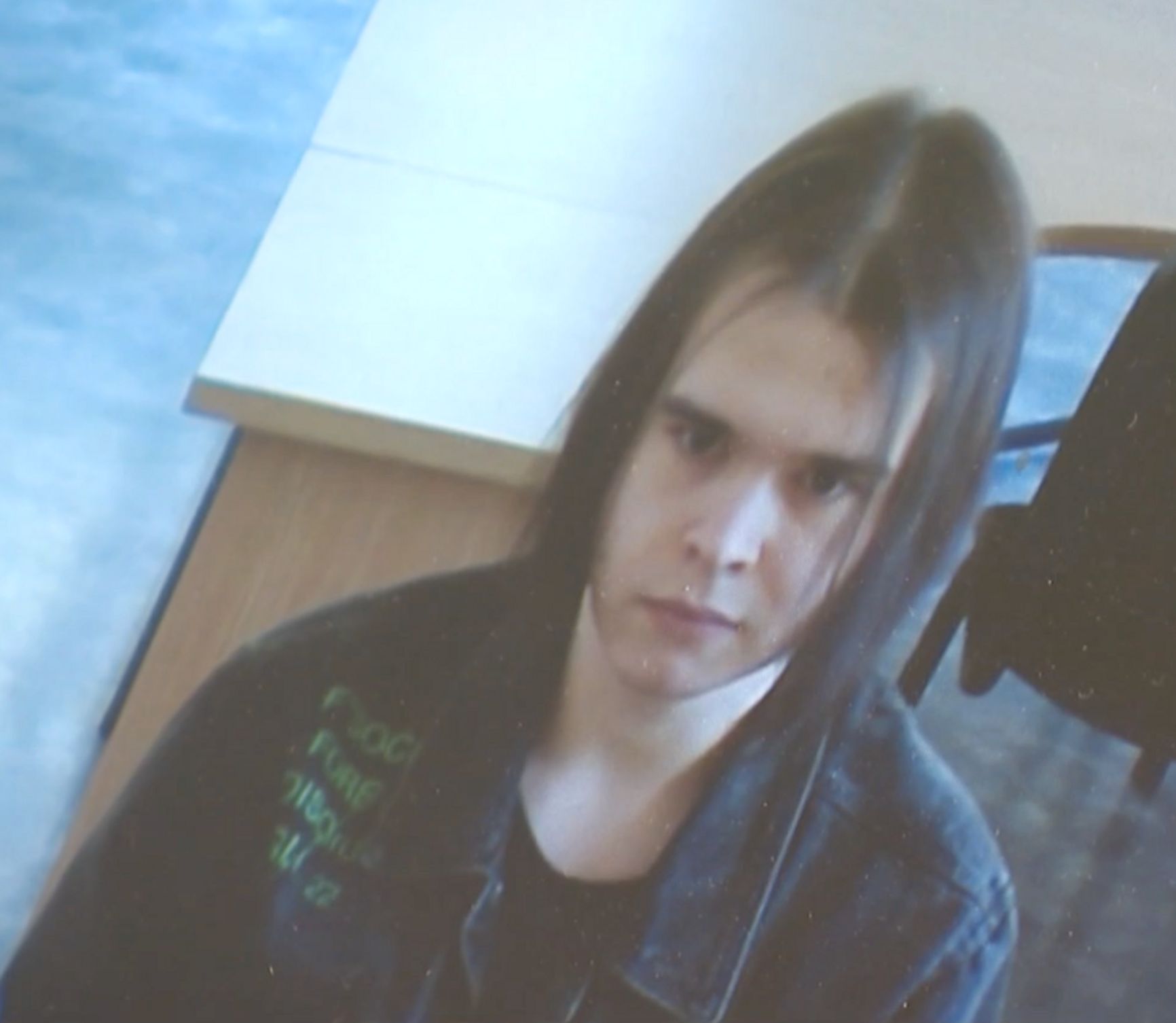

But the same was not true of the company where Sergejs rented his Canon camera. He’d left a copy of his ID. His first name really was Sergejs, and his surname was Hodonovičs. He was 21 years old.

From here, investigators found him easily. He was arrested in April 2023. During a search of his apartment in a run-down district of Riga, they seized a phone containing photos of an abandoned military bunker in the woods — and also of Kante, the recommended soldiers’ haunt in Lielvārde.

A criminal case was launched against Hodonovičs for espionage on behalf of Russia. “It can be asserted that S. Hodonovičs's activities fall within the tasks assigned by the Russian Federation’s GRU,” the investigation stated.

***

Dressed in a denim jacket with fleece lining, his hair shoulder-length and his beard three days’ worth of stubble, Hodonovičs sits slumped in his interrogation video at VDD headquarters. He recounts how he met a man nicknamed “Green” while searching for marijuana on Telegram chats. Green was looking for someone to go to Estonia and “draw something” with spray paint. Hodonovičs agreed.

In April 2022, two months after Russia invaded Ukraine and a month before he dropped the note in Rembate, Hodonovičs left work early and boarded a bus headed to Estonia’s capital, Tallinn. Along the way, Hodonovičs received instructions that his partner for the job was on the same bus with cans of spray paint. The accomplice turned out to be short, around 18 years old. Hodonovičs dubbed him “the Kid.” “He was irritable and spoke Russian,” Hodonovičs told interrogators. “The Kid had the location on his phone.”

After getting off the bus, the two walked for about an hour until they reached a concrete wall. They were to spray an image the Kid had received from the anonymous client on his cellphone. Neither understood exactly what the writing meant, but after tagging the wall with orange-red letters, they took a photo of their work, sent it to the client, then boarded a bus for the return journey back to Latvia. Hodonovičs received 400 euros.

The next morning, police received a call from a passerby that the outer walls of a military complex that houses the NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Center of Excellence (Cyber Defence Center) had been vandalized. The blood-orange message read, “Killnet hacked you,” and it was repeated multiple times across 620 feet of the long, encompassing barrier. Killnet is a Russian-language hacking group known for offering DDoS attacks as a service. When Russia launched the war in Ukraine on February 24, 2022, Killnet quickly announced its full support for Moscow.

Nor was the criminal daubing the extent of this operation. At the same time, several Estonian online state services and websites, including that of the Cyber Defence Center, suffered distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks, resulting in some being temporarily taken offline. Estonia has been a frequent target of Russian cyber attacks — the worst one occurring in 2007 as retaliation for the relocation of a Soviet-era World War II monument from a busy city intersection in central Tallinn to a military cemetery. The so-called Bronze Soldier affair shut down some of Estonia’s digital government and economic infrastructure, causing the country to ramp up its cybersecurity capability. Today it is one of the leaders in the field in NATO, hence the Cyber Defence Center. This virtual attack, however, was different because it wasn’t just virtual: it coincided with a physical message on Estonian soil.

The country’s cyber crime unit of the central criminal police mapped the attackers and the tactics they were using, likening them to “kids throwing pebbles at windows from a distance,” according to Ago Ambur, the head of the unit. The attackers never penetrated any networks, Ambur added; at best they managed to take a website or service down for a short while, but nothing like 2007.

Meanwhile, another unit in Estonian law enforcement investigated the graffiti. City traffic cameras soon revealed that a taxi took two men to a bus stop near the admittance gate of the Cyber Defence Center. The Insider, Re:Baltica and Delfi have obtained that CCTV footage. It was a little after half past one at night. It took the men more than an hour to graffiti their message. They left the site on foot shortly after 3 a.m.

Photographing the military airfield in Lielvārde was a much more arduous task. The Telegram chat automatically deleted messages, so Hodonovičs wrote the instructions on paper. Following the client's directions, he bought two memory cards. On one of them, he took “random photos, just in case someone asked.” On the other, he captured specific targets from four locations. He sent the photos from his phone to the client. For this job, Hodonovičs was paid the same amount as the “Killnet” vandalism: 400 euros.

In the criminal case files, Hodonovičs's testimonies are inconsistent, but it is evident that he received assignments from multiple people who knew each other.

One of them is the aforementioned Green, whose real name is Gļeb. Gļeb’s daily business involved money laundering by recruiting “mules” — decoy bag men who withdraw cash from ATMs or allowed their personal information to be used to open banks accounts, in this case at Revolut, a British online financial services company. Hodonovičs also assisted Gļeb in the latter’s mule business. On one occasion, he took a taxi for a five-hour drive from Riga to a hotel in Tallinn, received a bag full of euros from a stranger, then brought it back to Latvia.

Gļeb also acted as a remote recruiter-agent, helping a contact he met on Telegram find people for various tasks, earning a commission for each successful match. For finding Hodonovičs to paint the graffiti in Tallinn, Gļeb earned 100 euros. During interrogation, he testified that his orders varied in severity from vandalism to arson.

The taskings, or “ads,” as they were called, came with photos. One included instructions on how to set fire to a church in Ukraine. Gļeb claimed he didn't know the client personally; he frequently changed his phone numbers and usernames. (A separate criminal case in Latvia has been opened against Gļeb, and the investigation is ongoing.)

But Gļeb was just a link in a longer chain, as was Hodonovičs. A more important link was another intermediary involved in Hodonovič's assignments, known by the username MOT. But who was he — or she?

***

Investigators started by analyzing the payments made to Hodonovičs for photographing the military airfield.

Over several transactions, 630 euros had been transferred to him by a man named Timurs. Timurs testified that he had lent his Revolut card to MOT, whom he identified as a former classmate from the Latvian Maritime School. Further investigation revealed that several other classmates had also lent their Revolut accounts to MOT. The intermediary used these accounts to convert cryptocurrency received from another participant — “Alexander” — into euros to pay Hodonovičs and other operatives.

MOT was arrested in 2023, two days after Hodonovičs, in an apartment in Purvciems, a district in Riga known for its brutalist, Soviet-era apartment blocks and its large Russian-speaking population. His real name was Martins Griķis, and he was 20 years old.

In the interrogation video, Griķis, wearing a dark red sweater and sporting a close-cropped haircut, answered questions matter-of-factly. Before starting his collaboration, he said, he had received his instructions from yet another anonymous user on Telegram: the aforementioned “Alexander.” Alexander, however, knew the legal names of everyone he connected with in this online wilderness of mirrors. He demanded a copy of Griķis’s passport and a brief curriculum vitae. “To work in this field, you had to send your passport photo,” Griķis explained to the investigator.

Alexander requested permission to deposit cryptocurrency into Griķis's account, convert it to euros, and then forward the money. In more than two years, Griķis earned about 10,000 euros in commission for his services. (The total amounts transferred are not mentioned in the criminal case.)

Griķis's role also included talent-spotting new operatives for tasks ordered by Alexander and vetting these agents for reliability. For each successful recruitment, Griķis received cryptocurrency in amounts between 500 and 2,000 euros. He converted the funds, paid the operatives, and took his cut, which was often a high percentage of the agent’s own compensation — or even more than the agent.

He earned well.

For instance, while Hodonovičs earned 400 euros for photographing the Latvian military airfield, Griķis received a 200 euro commission.

For the graffiti op in Tallinn, Griķis received 2,000 euros from Alexander. Hodonovičs testified that he was paid 400 euros for the job. Nevertheless, Griķis also covered travel expenses, the cost of the spray paint, and a fee for the Kid.

The Kid boasted that defacing the Estonian Cyber Defence Center wasn’t his first job. In January 2022, a month before Russia's all-out attack on Ukraine, he’d traveled to Kyiv to throw a homemade Molotov cocktail into the ventilation shaft of a military facility. The aim was to burn down the whole thing.

The Latvians have since identified the Kid as Ivan Tarabanov, a Russian-speaking Latvian national. His digital handlers sent him a PDF with instructions on how to make a Molotov cocktail and the need to take two sets of clothes — one dark-colored for committing the arson, and one casual for slipping the scene undetected. The handlers even bought him a plane ticket to Kyiv. Tarabanov took a taxi from the airport to a nearby gas station to buy the petrol for the Molotov cocktail. But the operation failed. Tarabanov got scared and set fire only to the building’s exterior wall. He then took a bus from Kyiv to Poland and from there returned to Riga.

The Ukrainian military facility targeted in the attempted attack has not been disclosed in the Lativan investigation. “Our security services didn’t want to bother the Ukrainians too much,” prosecutor Salvis Skaistais told The Insider. “They had enough on their plate with everything burning there already. The war had begun.” A separate criminal case has been opened for arson. The trial is ongoing.

Ivan Tarabanov, or Kid, tried to set a building on fire with a Molotov cocktail in Kyiv

Photo: LTV

Griķis testified that he coordinated with several other people whose contacts were provided by Alexander. During the search of Griķis’s home, investigators found several recordings of “job interviews.” In one, a potential recruit mentioned being in Ukraine and expressed his willingness to commit arson for money, but not to kill anyone.

In his interrogation, Griķis mentioned that a Ukrainian citizen had traveled to Ukraine from Latvia to paint the Russian military symbol “Z” on unnamed structures. Another person from Latvia agreed to throw a Molotov cocktail into a building, but he chickened out completely and never went.

In Latvia, Alexander and Griķis sought both citizens and non-citizens to carry out these tasks. The core requirement was that none of the subagents hold Russian citizenship, which would arouse suspicions when entering Ukraine if not bar entry altogether. According to Griķis, Alexander was also looking for people to start fires in villa districts in France or to work in drug manufacturing labs in Russia. Griķis found one recruit for the latter job.

The “business” had its downsides. Often, Griķis would find a recruit, buy tickets, and provide an advance payment, only for the “employee” to disappear.

“At first, drawing graffiti or taking photos doesn't seem that dangerous,” VDD chief Mežviets told The Insider. “But throwing a Molotov cocktail into a house, especially knowing there might be victims, is something even people with criminal backgrounds won’t easily undertake.”

Many “employees” have rough backgrounds and rap sheets, Hodonovičs and Tarabanov included. “The criminal underworld is fertile ground for finding such people,” said Latvian State Police Chief Armands Ruks. “If they have the inner conviction to commit crimes, they make good candidates.”

This was evident in the February arson attempt at Riga’s Museum of the Occupation, dedicated to memorializing the victims of the Soviet occupation of Latvia. The assailants — two men and one woman — broke the window of the museum director’s office with a hammer and tossed a Molotov cocktail into the building. The fire was quickly extinguished. Police soon found one of the culprits — he left his mask and gloves at the scene, and his DNA was already in the police database due to previous drug offenses. It was soon revealed that one of the men was recruited through a Telegram channel managed by an inmate in one of Latvia’s largest prisons. Mobile phones are technically banned in prisons, but lapses in enforcing this restriction are notorious.

Latvian Interior Minister Rihards Kozlovskis described the attack on the Museum of the Occupation as part of Russia's hybrid war and emphasized the symbolic significance of the chosen target.

“If the rescue service had not arrived in time, a serious fire could have broken out, possibly destroying the exhibit, which would have caused a significant public outcry and achieved the intended goal,” Kozlovskis said.

***

But who is Alexander, the ringleader intermediary of the Latvian spy ring?

This remains one of the biggest unanswered questions in the Hodonovičs case.

Griķis testified that he had never met Alexander in person but that they had spoken on the phone, with Alexander always ringing while drunk. At one point, Alexander mentioned his real name was Vadim and that he hailed from Dnipro, a sizable city in central Ukraine. He claimed to be 25 years old and a chef by trade.

The Latvian case files do not contain documents proving Alexander’s affiliation with the GRU. That assumption is based on information provided by Latvian security services. Prosecutor Salvis Skaistais explained to The Insider that both Griķis and Hodonovičs had confessed to engaging in espionage for Russian special services, indicating they knew who they were working for.

At one point during his interrogation, Hodonovičs was asked by an investigator about photographing the airfield: “But you realized this is a military site, not some school project, right?”

“Well, yes,” Hodonovičs replied, “but he said it wouldn’t be sent to anyone, that no useful information could be obtained from it anyway.”

This defense did not hold up in court. On appeal, the judge sentenced Griķis to three years in prison and Hodonovičs to two years and eight months.

Tarabanov, who set fire to the military facility in Kyiv, testified that he did not know about Alexander’s connection to the GRU. He thought him a mere gangster who intimidated people if they failed to carry out the crimes he paid them to do. The court verdict in this case is expected in the autumn.

All three saboteurs — Tarabanov, Hodonovičs, and Griķis — declined interviews with The Insider.

Normunds Mežviets, the chief of Latvia’s VDD security service, said that creating long chains of go-betweens for task execution is a deliberate strategy of the Russian special services, as it complicates the efforts of law enforcement to trace their provenance. A source familiar with the case suggested that Alexander might not be a GRU officer himself but rather an unwitting agent recruited by Russian military intelligence to scout others in foreign countries.

Latvian State Police Chief Armands Ruks also explained that operatives are intentionally recruited from other countries to confuse or complicate law enforcement.

“We don't have border control,” Ruks said. “A person comes in as if on a business trip and leaves. It's also harder to trace their past if they're not from Latvia.” To bolster security, surveillance cameras have increasingly been installed on national highways in Latvia.

Operatives of GRU Unit 29155, a bespoke assassination and sabotage squad, have been responsible for more than a decade of mischief, blowing up ammunition and weapons storage facilities across Europe and poisoning Sergei Skripal, a GRU defector-turned-British agent, and Emilian Gebrev, a Bulgarian arms dealer, using a Russian-made military grade nerve agent.

Unit 29155’s ability to travel to EU and NATO territories — even under false identities — has been eliminated thanks largely to The Insider’s work exposing their operations and unmasking their cadres. As a result, the GRU has begun to rely on amateurs and hirelings to do its dirty work, a development that will no doubt lead to sloppy or botched operations and thus increase the likelihood of collateral damage. One Russian-Ukrainian saboteur immolated himself in June in his hotel room in France while constructing a homemade bomb, according to French authorities.

European security services are intensifying cooperation at the international level. In January of this year, a dual Estonian-Russian citizen was detained at the Latvian-Belarusian border for defacing national memorial sites in Latvia and Lithuania. The arsonists who targeted Lithuania's IKEA were detained in Poland.

In May, Latvian Prime Minister Evika Siliņa expressed gratitude to the VDD for collaborating with Polish and Baltic services. This followed the arrest of nine Russian spies in Poland connected to sabotage plans in the Baltics, and possibly in Sweden.

“The detention of the Russian special services group is a very good result of our services' cooperation,” Siliņa said. “The services have been monitoring these activities for a long time and have prevented several operations by groups working for Russia, as well as multiple crimes in our territory.”

Šarūnas Čerņauskas from Siena (Latvia), Anastasiia Morozova from Vsquare (Poland) contributed to this investigation.