For more than a week, the Armed Forces of Ukraine (AFU) have held control over a sizable section of Russia’s Kursk Region — and have gradually expanded the zone of hostilities. Estimates suggest Ukrainian forces have seized between 500 and 1,100 square kilometers (193 to 425 square miles) of territory, capturing hundreds of Russian prisoners in the process. The AFU offensive crossed a so-called “red line” concerning the use of Western military equipment on internationally recognized Russian territory, challenging the belief that the mere possession of nuclear weapons ensures a country’s protection from ground-based military operations. But what are the ultimate goals of Ukraine's Kursk offensive? Kyiv, thus far, has not announced its objectives. The Insider explores the possibilities.

Content

What happened?

What goals are the Ukrainian operation pursuing?

How is Russia reacting?

How events may develop further

What happened?

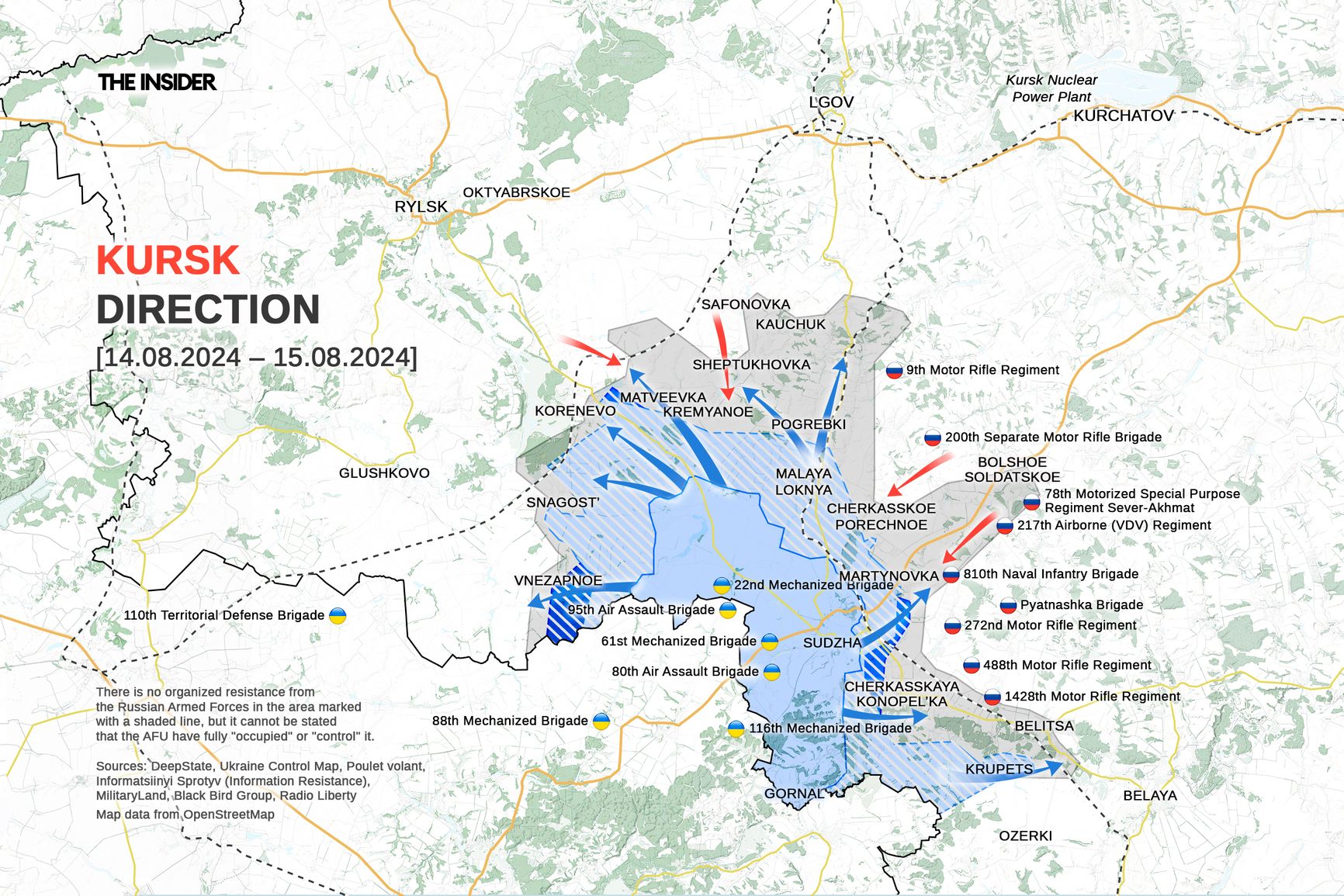

On the night of August 6, AFU units launched an attack on multiple points along Ukraine’s border with Russia’s Kursk Region, breaking through and advancing toward the districts of Sudzha, Korenevo, and Lgov. According to the Russian Defense Ministry’s official account, the attack involved only 300 Ukrainian servicemen from the 22nd Mechanized Brigade, supported by 11 tanks and more than 20 armored fighting vehicles (AFVs). On the same day, the ministry claimed the Ukrainian group was “defeated,” but later edited the post, omitting the portion of the statement that asserted Ukrainian forces had “suffered significant losses and retreated to Ukrainian territory.”

By August 7, AFU units had occupied up to 11 settlements, advancing up to 15 kilometers (9 miles) deep in an area of Russian territory 10-11 kilometers (6-7 miles) wide, reaching the center of Sudzha and reportedly capturing a significant part of the town. During the early days of the operation, Ukrainian troops gained operational freedom, and raiding groups conducted operations at a considerable distance from the internationally recognized border. Only by August 9 did the Russian Armed Forces manage to stabilize the situation in some areas, according to Russian pro-war sources.

Nevertheless, the initiative remains in the hands of the Ukrainian command, and a fixed line of contact has not yet been formed. According to official information from the Russian Ministry of Defense (1, 2, 3), the AFU is continuing its attempts to build on its gains all the way up to the administrative border of Russia’s neighboring Belgorod Region.

The initiative in the Kursk Region is in the hands of the Ukrainian command

The area of the zone of hostilities in the Kursk Region has been estimated to be from 480 square kilometers to more than 1,000 square kilometers (185 to 385 square miles). Alexei Smirnov, the Kursk Region’s acting governor, reported on August 12 that a total of 28 settlements have been lost, with the Ukrainian breakthrough reaching 12 kilometers (7.5 miles) in depth and 40 kilometers (24.8 miles) in width (a potential area of 480 square kilometers, or 186 square miles). Smirnov was notably cut off by Putin when he mentioned the depth of the Ukrainian army’s advance into Russian territory. Putin remarked that the governor had stepped outside of his mandate and that military matters were best left to the Ministry of Defense (MoD).

AFU Commander-in-Chief Oleksandr Syrskyi has reported (1, 2, 3) to Volodymyr Zelensky on the progress of his forces, which now have control over over 1,100 square kilometers (425 square miles) of Russian territory, along with 82 settlements. According to the non-governmental open source intelligence (OSINT) project DeepState, the Ukrainian military controls about 800 square kilometers (308 square miles), while another 230 square kilometers (88 square miles) is characterized as a “gray zone” — meaning the situation there is unknown.

The AFU’s successes can be attributed to “operational surprise” achieved by secretly concentrating significant forces at the border under the guise of preparing to repel a possible Russian offensive on Sumy Oblast — along with overwhelming military-technical advantages, including in the areas of electronic warfare systems and UAVs. The Ukrainian offensive has also involved numerous armored vehicles (including Western models), engineering vehicles, and scarce air defense systems, along with helicopters and possibly aircraft carrying Western-supplied guided munitions.

The AFU’s successes can be attributed to “operational surprise”

In addition, unlike Ukraine’s previous limited raids in Russia’s Bryansk, Kursk, and Belgorod regions, this time the battles are being fought not by the reconnaissance units of Ukraine’s Main Directorate of Intelligence (HUR), but by “line” AFU brigades — i.e. regular forces. Many commentators are drawing comparisons between the current maneuvers in the Kursk direction and the operation near Kharkiv in the fall of 2022, particularly the breakthrough near Balakliya. Notably, as in that earlier campaign, Ukrainian forces under the command of Oleksandr Syrskyi are facing a grouping led by Russian General Alexander Lapin.

What goals are the Ukrainian operation pursuing?

There is a debate on this issue, with four likely possibilities.

- Diverting Russian troops from other directions

The minimum objective of Ukraine's offensive may be to create a crisis significant enough to divert the Russian Armed Forces from the theater of operations on internationally recognized Ukrainian territory. This could potentially stall the ongoing Russian offensive in Donbas, where Russian troops have been making tactical gains at great cost for several months. The maximum goal likely involves directly weakening the areas where the current Russian offensive is underway, setting the stage for a Ukrainian counterstrike.

According to a report by Agence France-Presse (AFP) citing a senior Ukrainian official, one of the AFU’s aims in Kursk is indeed to “stretch” the enemy's forces. However, The Economist has reported that Russian commanders are deliberately delaying the deployment of troops and equipment to the Kursk area, contrary to Ukraine's expectations. “Their commanders aren’t idiots. They are moving forces, but not as quickly as we would like. They know we can’t extend logistics 80 or 100 km,” an anonymous source in the Ukrainian General Staff told the publication.

The Russian command is in no hurry to transfer reserves to the Kursk Region

If the Donbass offensive does grind to a halt due to the redeployment of Russian reserves, that would be a significant success for Ukraine. So far, however, there has been little movement of units from that area.

- Strengthening of negotiating positions

Few noticed, but just before the offensive in the Kursk Region, President Volodymyr Zelensky mentioned that Ukraine was preparing “a real foundation for a just end to this war already this year.” After that, presidential advisor Mykhailo Podolyak said that the AFU operation was having a positive impact on Ukraine’s possible negotiating position.

Vladimir Putin, on the other hand, is trying to show that it makes no sense to negotiate now (which indirectly confirms that a weakening of his negotiation position is taking place):

“Apparently, the enemy seeks to improve its negotiating position in the future. But what kind of negotiations can we even talk about with people who indiscriminately strike civilians, civilian infrastructure, or try to threaten nuclear power facilities? What can we even discuss with them?”

Dmitry Polyansky, Russia's acting envoy to the United Nations, viewed the events in Kursk as Kyiv’s rejection of Moscow’s “generous offer” of peace talks. Putin's “generous offer” was, in fact, a demand that Ukraine withdraw its troops from the Ukrainian regions of Kherson, Zaporizhzhia, Donetsk and Luhansk, sign a pledge not to join NATO (or any other military alliance), and succeed in having all international sanctions against Russia lifted.

The Kremlin sees the AFU offensive as a rejection of peace talks

Regarding Putin's mention of threats to nuclear facilities, reports from Russian pro-war sources (1, 2, 3) indicate that Moscow is concerned about a potential for Ukraine to seize the Kursk Nuclear Power Plant in Kurchatov and use it as an instrument of “nuclear blackmail.” Although there have been reports of Ukrainian reconnaissance groups coming within 18.5 kilometers (11.5 miles) of Kurchatov, the notion that the AFU could capture a nuclear power plant as a bargaining chip seems implausible. Moreover, the plant is too far from the border for Ukrainian forces to maintain effective control and secure the flanks of a potential Russian breakthrough toward Kurchatov.

- Improving morale in Ukrainian society and the army

Since late 2022, the AFU has not made any notable territorial gains, and the ongoing war of attrition — involving the near total destruction of Ukrainian population centers along the front line in the Donbas, along with frequent Russian aerial attacks on cities deeper in the rear — is having a detrimental effect on the mood of servicemen, leading to increased desertion, among other things. A Financial Times correspondent who traveled to the border area of Sumy Oblast reported on the improved morale and psychological state of the Ukrainian soldiers taking part in the operation.

- Destabilization of the situation in Russia

If official reports are accurate, 121,000 of the 180,000 people living in the affected areas of the Kursk region have been evacuated, potentially leading to a large-scale humanitarian crisis. Additionally, nearly all residents of the Krasnoyaruzhsky District in the neighboring Belgorod Region have fled, and a mass exodus from other border areas cannot be ruled out. Such challenges, previously faced only by Ukrainians, now confront Russia, and it remains to be seen how regional and federal authorities will manage them. For the Ukrainian leadership, the objective of “bringing the war to the enemy's territory,” with all its associated costs, appears to hold value in and of itself.

In any case, it is important to recognize that, from a purely military standpoint, the AFU operation in Kursk Oblast was unlikely to achieve significant strategic objectives, as the region lacks large troop concentrations, vital military infrastructure, or major political and economic centers. However, according to some estimates, control over the railroad junction in Sudzha will damage the logistics of the Russian grouping fighting in the north of Kharkiv Oblast — a point echoed by Ukrainian presidential advisor Podolyak.

How is Russia reacting?

Russia’s reaction has been peculiar. Initially, the forces covering the border in the Kursk Region were made up of units with limited combat capability. These included territorial defense units, conscripts, border guards, and the Russian National Guard, a collection that proved unable to mount sustained organized resistance, leading to the capture of at least several hundred personnel (some estimates put the total number of Russian POWs at 1,000). Reports suggest that soldiers from the Chechen Akhmat unit abandoned their positions with little to no engagement in combat (1, 2). Fortifications constructed at a cost of more than 15 billion rubles (over $168 million) did not help either.

Russian pro-war commentators have acknowledged (1, 2) that, due to the lack of heavy equipment and the disruption of electronic communications by the Ukrainians, n the first days of the offensive the only Russian force countering the AFU’s advance was aviation — not only in the sky, but on the ground, too. Reportedly a motorized infantry unit drawn from the Russian Air Force personnel engaged Ukrainian soldiers near the town of Korenevo. At first, the AFU's equipment was only targeted with operational-tactical missiles and Lancet drones.

Vladimir Putin described the AFU offensive as a “large-scale provocation,” assigning First Deputy Prime Minister Denis Manturov to oversee the “situation” in Kursk Oblast and announcing a counter-terrorist operation (CTO) in the region, as well as in neighboring Bryansk and Belgorod Oblasts. However, it is still unclear whether Russia’s response will be led by the “North” Grouping of Forces under General Alexander Lapin, whose area of responsibility includes the region, or by the Federal Security Service (FSB), given the CTO's legal framework.

It is still unclear who is in charge of Russia’s response to the Ukrainian offensive in Kursk

Dara Massicot, a Senior Fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, noted that the CTO regime used during the Second Chechen War was an example of effective cooperation among various security agencies. Today, both FSB head Alexander Bortnikov and Chief of the General Staff Valery Gerasimov have relevant experience from Chechnya. However, the CTO headquarters has not yet been formed, and it remains unclear who will lead it, as the commanders of Russian military districts (and, by extension, troop groupings) are currently focused on operations in Ukraine.

A mix of units with questionable combat capabilities and evident personnel shortages is being assembled in place of a full-fledged troop grouping in the Kursk Region (some commentators have called them a “scattering of leftovers”). This includes the Pyatnashka Brigade (also known as the “Donbas Wild Division”), which featured a Porsche Cayenne as part of its military convoy. Various volunteer units like Sarmat and Che Guevara have also reportedly gotten involved.

The Russian command seemingly lacked operational or even tactical reserves in the Kursk area and has now been forced to improvise while trying to avoid diverting combat units from the front lines in Donbas. Hence the haste and confusion, fraught with incidents like the HIMARS strike on a convoy near Rylsk.

The chaotic anti-crisis media campaign deserves a separate mention, with Russian state media publishing geolocatable videos of military vehicle movements and the Russian Defense Ministry falsifying footage of strikes that, contrary to Russian claims, were not carried out in the Kursk combat zone.

How events may develop further

Attitudes toward the Kursk operation appear to have evolved over time. On the first day of the incursion, Ukrainian reserve officer and military analyst Tatarigami_UA sharply criticized the AFU's move, arguing that diverting forces to this region, especially given the critical situation created by a personnel shortage in the Donbas, lacked strategic sense and even “bordered on mental disability.” Prominent U.S. military expert Rob Lee doubted the choice of the strike direction, noting that the Russian command is already engaged in the operational area in northern Kharkiv Oblast with well-established supply lines. John Helin, an OSINT analyst at the Black Bird Group, noted that holding the captured territories in Kursk Oblast would require significantly more resources than the Ukrainian command has at its disposal.

Later, however, the tone began to change.

Emil Kastehelmi of the Black Bird Group does not rule out the possibility of similar operations by the AFU in other parts of the front — by creating an operational crisis in Kursk Oblast, he argued, Ukrainian forces could exploit vulnerabilities and attack elsewhere. In Kursk itself, significant impact would only be expected with a deeper advance toward the city of Kursk, a development that does not appear likely.

Retired Australian Major General Mick Ryan noted that the unexpected Ukrainian offensive has shaken the emerging conventional wisdom that operational surprise and offensive actions are impossible to achieve on today's “transparent” battlefield. Ryan suggests that once the current phase of the operation is over and the front stabilizes, the AFU command will have three main options to choose from moving forward.

Once the current phase of the operation is over and the front stabilizes, the AFU command will have three main options to choose from moving forward

The first option is to establish defenses along the newly gained lines and hold them until negotiations can occur. Although this would still pose a serious threat, forcing the Russian army to redeploy additional reserves, Ryan considers it the riskiest choice, since the numerous “bulges” of Ukrainian positions that have formed can be easily “cut off,” resulting in heavy losses.

The second option is to withdraw to more favorable positions on Russian territory and build defenses there. This approach is less risky, requires fewer resources, and allows for the redeployment of forces to other fronts. It would also offer strategic and political benefits, such as strengthening Ukraine’s negotiating position.

The third option is to withdraw entirely from Russian territory and return to the international border. This would preserve the Ukrainian forces for use in other areas while signaling to Russia — and to Ukraine’s Western allies — that Kyiv is capable of executing complex, large-scale offensive operations on enemy soil.

Be that as it may, the Ukrainian command has opened a new operational area that will require the use of scarce military resources. According to current estimates, individual units of more than six AFU brigades — but not brigades in their entirety! — are involved in the operation. The total number of troops involved is almost certainly not more than 10,000, and that includes those in rear and auxiliary units in Sumy Oblast. At the same time, these are some of the most combat-ready and well-equipped units of the Ukrainian army, and it is still unknown what the forces of the second and third echelons are (and whether they exist at all, and under what conditions they are expected to enter combat). For the current AFU grouping, the most attainable objectives appear to be reaching the Rylsk-Kursk highway and expanding the zone of control in areas close to Ukrainian territory, where logistical support is more manageable.

If the line of contact solidifies along the current positions held by Ukrainian forces in the Kursk Region (excluding the raid operations zone), approximately 150 kilometers (93 miles) of new frontline will emerge. Given that a battalion typically defends a front of 5 to 10 kilometers (3 to 6 miles), the Russian Armed Forces would need to deploy 15 to 30 battalions to the area — along with all of the necessary reinforcements. With each battalion comprising about 500 troops, this would require a force of 7,500 to 15,000 soldiers, not including additional support units such as artillery, air force, and reconnaissance.

However, the seizure of such a large part of Russian territory would present more of a political than a military problem. The Ukrainian leadership may assume that the Kremlin will prioritize dislodging the AFU from the Kursk Region as quickly as possible, regardless of the cost in casualties. For a counteroffensive, the Russian command would need to assemble a force at least twice as large as Ukraine’s — up to 30,000 troops — along with substantial artillery and armored units.

The Kremlin may try to dislodge the AFU from Kursk region as quickly as possible, regardless of the cost in casualties — it will need up to 30,000 troops for a counteroffensive

But Ukraine does not need to secure further Russian territory — or even to hold all of the areas it already controls — in order for its Kursk operation to qualify as a success. One of the important, and already evident, results of the AFU’s Kursk operation is that the so-called “red lines” regarding the use of Western military equipment (Stryker APCs, Marder IFVs, HIMARS MLRS) have been crossed without any significant consequences.

The Pentagon has called AFU's actions “consistent” with U.S. policy and noted that Ukraine can “defend itself from attacks” with U.S. weapons in this way. German authorities have also made it clear that they are not decisively opposed to the use of German military equipment on Russian territory. The UK government, for its part, has said that “there has been no change” in its position, as it has not given approval for Kyiv’s use of Storm Shadow / SCALP-EG missiles in the Kursk offensive. As per the The Washington Post, Ukrainian officials have again requested permission from the White House to fire U.S.-made ATACMS missiles at internationally recognized Russian territory in support of the Kursk operation and its objectives.

Another notable intermediate outcome is that Russia's nuclear deterrent is being eroded before our eyes. The armed forces of a non-nuclear state have invaded Russian territory, and Russia has been unable to halt the advance using the means at its disposal.

Having launched an operation to create a “sanitary zone” around Kharkiv in May 2024, purportedly to protect the Russian border area from Ukrainian shelling, Vladimir Putin first achieved a fivefold increase in missile attacks in the Kursk Region alone, and now finds himself with a “sanitary zone” on his own territory. At least, that’s how the Ukrainian Foreign Ministry justifies the offensive.

Cover photo: Ukrainian military vehicles pass a sign reading 'Ukraine' (left) and 'Russia' (right) near the destroyed Russian border post on the Russian side of the Sudzha border crossing with Ukraine, on Monday, August 12. Source: David Guttenfelder / The New York Times