From satellite imagery, geolocation services and mobile coverage to facial recognition, artificial intelligence and drones: over the past 10 years digital technology has dramatically changed the concept of modern warfare and has become an essential part of the process of identifying and documenting war crimes. Techniques honed during the Syrian conflict are already being actively used today to investigate the Russian attack on Ukraine aided by satellite imagery, drone video, big data analysis, AI-based facial recognition, and more. However, due to the inertia of the legal system, digital evidence is still difficult to use in an international court.

Content

New digital reality

Satellites and drones help gathering evidence

Big data analysis for proving complicity in war crimes

How to prove a war crime in The Hague

From satellite imagery, geolocation services and mobile coverage to facial recognition, artificial intelligence and drones: over the past 10 years digital technology has dramatically changed the concept of modern warfare and has become an essential part of the process of identifying and documenting war crimes. Techniques honed during the Syrian conflict are already being actively used today to investigate the Russian attack on Ukraine aided by satellite imagery, drone video, big data analysis, AI-based facial recognition, and more. However, due to the inertia of the legal system, digital evidence is still difficult to use in an international court.

New digital reality

Russia's war against Ukraine is unprecedented in many ways, but especially important is this nuance: military conflicts have never before occurred in an area with such dense mobile and Internet coverage. When Russia bombed Syria in defense of Assad, only 30 percent of that country's population was online; during the withdrawal of U.S. troops from Afghanistan, 20 percent of Afghans used the Internet. In Ukraine today, 75% of the population is online.

In 2014 only 4% of Ukrainians had access to 3/4G networks, in 2021 as many as 80%; only 14% of Ukrainians in 2014 had smartphones, in 2020 their number exceeded 70%. Finally, about 4.6 billion people around the world are currently social media users, twice as many as in 2014. In addition, during this time, the largest content platforms have switched to algorithmic feeds that increase the visibility of materials that provoke rage, anger, and despair. The war in Syria has been called the «first viral war,» but the Ukrainian war is incomparably more viral and it's available live - both because of technological advances and because of the global media's biased view, in which the deaths of white people on the European continent are more horrific than those of others.

In two months we have seen that the high density of Internet coverage in the conflict zone is both an advantage and a vulnerability: the war is being mediatized by Ukraine to get the help and support it needs to defend itself; evidence of casualties and destruction appears almost immediately, often from territories still occupied by Russian troops; everything that has all the hallmarks of war crimes and crimes against humanity and can be recognized as such in the International Court of Justice is simultaneously documented by several independent parties. Surely the Internet also helps to avoid many casualties: for example, through warnings via the Dia app about impending missile strikes, p2p information exchange, and digital coordination of humanitarian initiatives. In such circumstances the aggressor's troops inevitably leave many digital footprints, making themselves vulnerable to the other side's combatants and investigators.

But this vulnerability also works the other way around: digital profiles of the population and Internet-linked Ukrainian infrastructure facilities are just as transparent to the Russian military and intelligence services; the invasion is known to have been accompanied by digital attacks from the Russian Federation; there have also been repeated reports of gig-work platforms being used to mark buildings in Ukraine for shelling and other intelligence activity. In her book In Defense of New Wars researcher Mary Kaldor offers the concept of «new wars» replacing «fourth generation warfare»: regular and irregular state and nonstate militaries clash, and the line between war and peace can be difficult to draw, the conflict is local and global at the same time, technology and digital solutions play an important role, and much of the violence is directed against civilians.

Russia's war with Ukraine is «new» in this sense, but it is difficult to call the actions of the Russian Federation, which has traditionally destroyed cities by airstrikes, technological. This time digitalization has played a really big role in the conflict by enabling documentation and fact-finding with a minimal time lag.

Russia's war with Ukraine is «new,» but it is difficult to call Russia's actions technological

Technologies that help investigate and establish responsibility in conflict zones can be divided into four groups: geospatial intelligence (GEOINT), financial intelligence (FININT), witness devices and applications - from smartphones and mobile cameras to wearable trackers, IoT devices («Internet of Things»: network-linked home and outdoor sensors) and applications that save data to blockchains, as well as online open source intelligence (OSINT), which often uses technologies from the first three groups and the data they produce.

Even at the stage of data collection, complexities arise depending on who collects the data, for what purpose, and how it is archived. In addition to the warring parties, at least four categories of actors can operate around a military conflict: humanitarian institutions, human rights institutions, international judicial institutions, and independent investigators and media. Ideally, their objectives should complement each other, but in practice this is not always the case. Additionally, different organizations have different access to war sites and information collection, and each may see their priorities differently, and thus may collect, share, and manage information differently. For example, the task of investigators and human rights activists at the borders of Ukraine and in the affected cities is, among other things, interviewing the victims and refugees from Ukraine en masse to collect evidence (as Human Rights Watch does, for example; it has already collected hundreds of interviews), while humanitarian organizations are interested in getting those people to safety as quickly as possible, and providing them with psychological help if necessary, to prevent re-traumatization with memories of atrocities.

Satellites and drones help gathering evidence

One of the most important pieces of evidence that the murders of civilians in Bucha had been committed while the city was under the control of Russian troops were satellite images from Maxar Technologies. On February 28, the company's photos showed the 64-kilometer convoy of Russian military equipment heading toward Kyiv, as well as extensive evidence of the destruction of civilian objects and residential buildings.

Mass graves in Mangush. Photo by Maxar Technologies

Satellite and U2 aerial images were first used as evidence in the international criminal trial concerning Srebrenica, a city in the former Yugoslavia where some eight thousand Bosnian Muslims were killed by Republika Srpska army soldiers in July 1995. The US authorities provided the images to the international tribunal on the condition that their source and method of production would not be discussed in court.

Pictures showed areas of freshly excavated earth 600-700 meters long next to the soccer stadium where the captured Muslims had been kept and shot. These were mass graves from which the executioners later removed some of the corpses to hide the scale of the crime. Extensive DNA testing helped uncover body parts buried in different locations, and the examination of the remains in secondary graves confirmed that those people had been killed with the same weapon. The evidence in the images was supplemented by sworn testimony.

In her book Cultures in Orbit Lisa Parks devoted an entire chapter to how the Srebrenica massacre was confirmed by American intelligence using satellite imagery: the selectivity, the delay in publication, the very nature of this aloof technological superpower's view of a «complex faraway region,» the unapologetic tone with which Madeleine Albright presented some of the imagery to the UN Security Council.

Since Srebrenica, satellite imagery has evolved from a tool for military strategists and private companies into a resource for investigating and prosecuting war criminals; its role has grown with the rise of private satellite companies and the increase in image resolution. Destruction and murder by military and paramilitary groups in the Central African Republic, Sudan, South Sudan, Congo, Myanmar, Niger Republic and several other places gained visibility particularly through satellite imagery. The existence of camps for Uighurs and other Turkic minorities in Xinjiang, denied by China, has been proven through satellite imagery, as has been the existence of camps for hundreds of thousands of political prisoners in North Korea.

The aftermath of a strike on the village of Abu Gudul in Sudan. Photo by AAAS

In 2017, the U.S. authorities concluded from satellite images that a crematorium had been built at the Syrian military prison of Seyd Naya, where regime opponents were allegedly burned in secret: snow on the roof of one of the buildings had melted although it still covered the roofs of the neighboring buildings, and air intake devices were visible. The existence of a crematorium, however, has never been proven; those who were incarcerated at Seyd Naya, where mass executions actually took place, had never heard of it. But the association of former detainees of that prison was involved in the search for mass graves in Syria, some of which were discovered in March this year based on testimonies and satellite imagery: several thousand people may have been buried there.

Satellite images have helped us to learn a lot about war crimes in Syria, but Kyle Glenn, the author of the OSINT tweeter account Conflict News, says that space visuals from Syria spanning several years are nothing compared to the satellite imagery of the war in Ukraine for just a couple of weeks. Remote sensing sometimes helps to get data in unexpected ways. For example, OliX, an oil market analyst, deduces the dynamics of oil production in Russia from NASA satellite imagery that captures brightness levels and the number of associated gas burning points at oil production facilities: the brighter the burn, the more associated gas and therefore oil; under the conditions of a war and sanctions, it is part of financial intelligence.

Space visuals from Syria spanning several years are nothing compared to the images of the war in Ukraine for just a couple of weeks

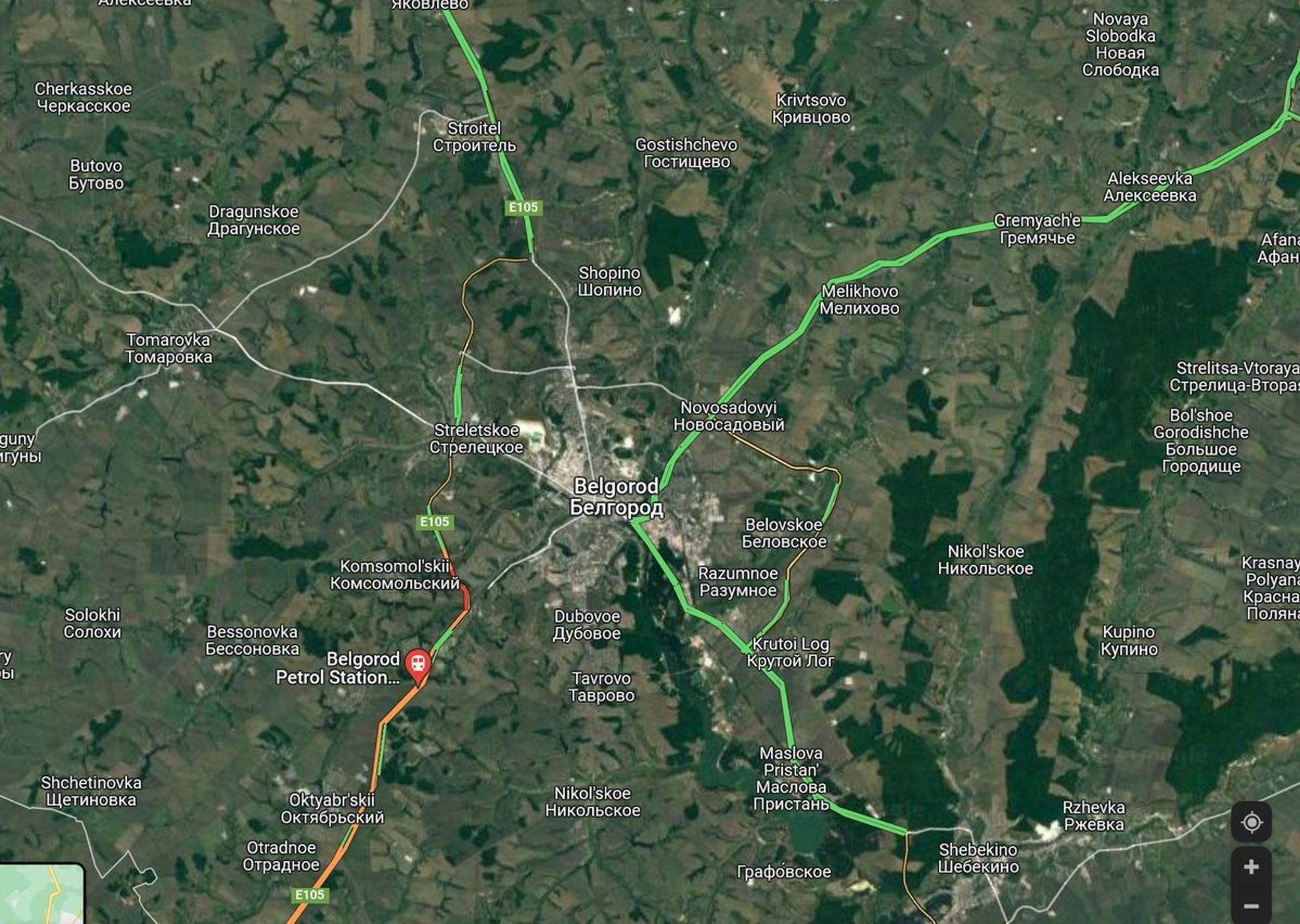

Satellites provide geolocation services like GPS, which is also one of the key technologies for finding out facts about the war. On the night of February 24, OSINT activists on Twitter watched on Google maps in real time as a giant traffic jam began to form on the Russian-Ukrainian border, where concentrations of troops had previously been recorded (probably not by soldiers with phones, but rather by locals stopping at roadblocks), and as it spilled over the border. Shortly before the war began, HawkEye 360 satellites detected the so-called GPS jamming by Russian equipment on the Ukrainian-Belarusian border north of Chernobyl - an already standard practice for jamming GPS satellites to camouflage and disorient the enemy. Such surveillance has the preventive function of remote sensing; American intelligence knew about the impending occupation of Srebrenica, but did not pay enough attention to it, although people on the ground understood that with the capture of the area there would be massacres.

In the case of the war with Ukraine, it was noted that the release of satellite imagery by Western intelligence slowed or thwarted some of the plans of the Russian command. In an international court of law, it is often more important to prove intent than to show evidence of a crime. So, based on a series of satellite images it is possible to trace recurring patterns in the movements and behavior of troops, accidental or non-accidental destruction of civilian targets, the mood of the armies and, consequently, the risks the population faces.

Traffic jam on the Russian-Ukrainian border on the night of February 24. Image from Dr. Jeffrey Lewis's Twitter account

Back in the '90s, navigation services helped identify and mark on the Field of Death map nearly 20,000 mass graves in Cambodia, where 2 to 3 million people murdered by the terrorist regime in the '70s had been laid to rest. In 2018, it was reported that Strava, a global heatmap activity app, showed movements and even personal data of the military, in particular - at U.S. bases in Afghanistan, as well as on the roads between those bases: fitness trackers and smartphones recorded the movements of people at sensitive points along with their profiles.

Conflict mapping today - from collecting valid data to displaying them - is a separate, complex task, as is damage mapping, including the destruction of civilian targets, that can serve as evidence of war crimes. For the military, satellite geolocation and maps are one of the key technologies, but as it turns out, the Russian army is not very good at it either: RFE has reported on the problems with Russian satellites: they are few, and those that exist have poor resolution and meager technical capabilities; there were high hopes for GLONASS in terms of navigational sovereignty, but only 23 of the 24 required satellites were launched, some of which will soon stop operating.

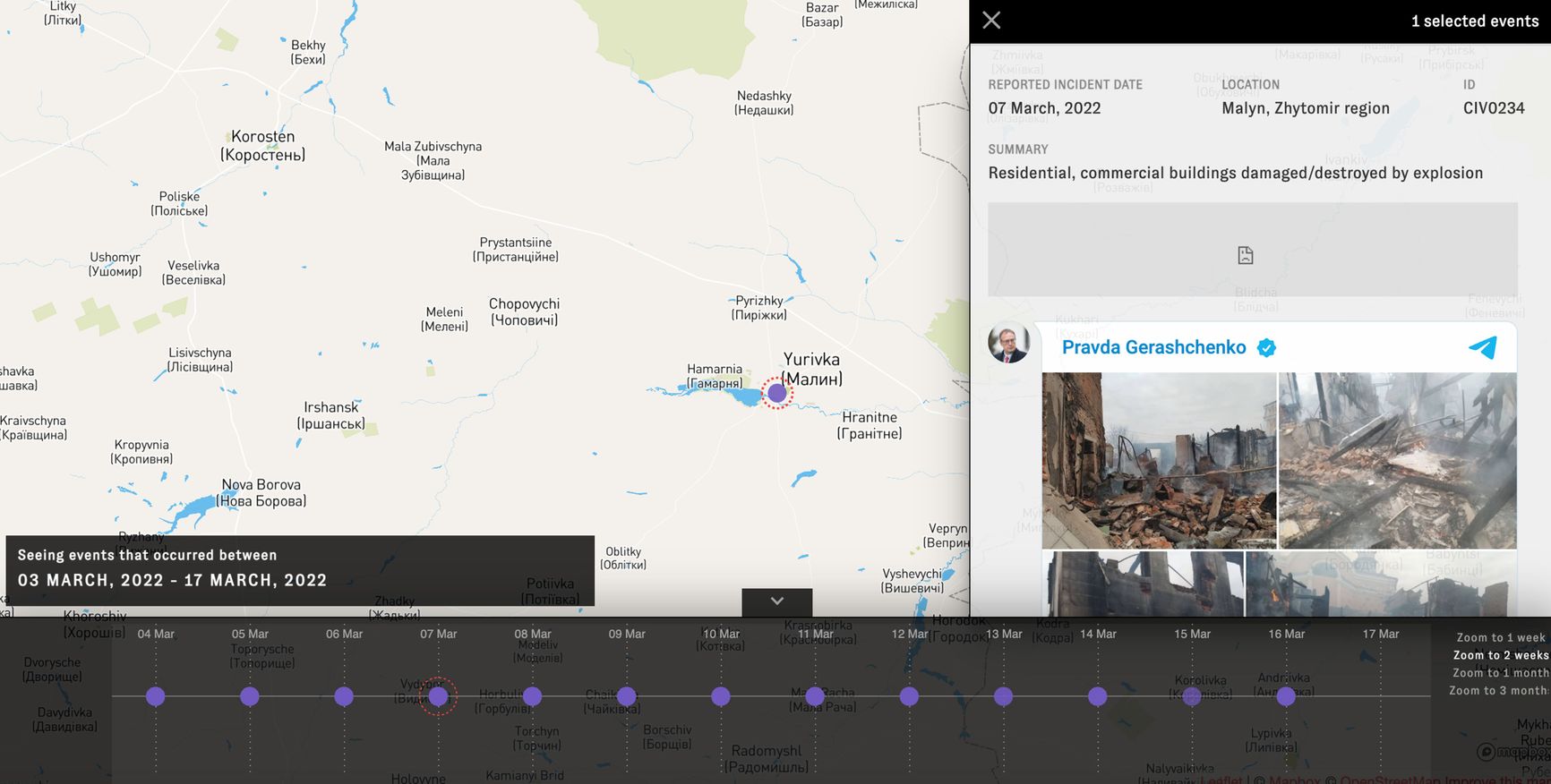

TimeMap screenshot with a specific incident highlighted. Screenshot by Bellingcat

Even during the Syrian operation there were reports of Russian pilots using commercially available Garmin navigators. Geospatial evidence of the war surfaced in unexpected places. For example, Twitter users reported on a Ukrainian whose house had been looted by the Russian military: he managed to find his AirPods in Belarus through the Locator app. Other evidence pointing to looting was discovered through camera footage of the Russian military sending large parcels from Mozyr, Belarus, and Novozybkovsk, Russia; the OSINT project Database posted a list of 69 senders along with their personal details, without specifying how the information was obtained; order numbers were tracked via SDEK and matched against the names on the posted list. Two-thirds of the parcels disappeared from pickup points or never reached their destination.

A Russian soldier with a bag from the Ukrainian shopping mall Epicenter. Screenshot from Anton Motolko's video

A couple of days before the start of the war, two U.S. spy drones were spotted over Ukrainian territory with the help of the Flightradar24 service. It is possible to track military equipment in this way, as well as through Marine Traffic or ADSB Exchange, as long as attempts are not made to hide it by disabling transponders. Archiving evidence of the presence of military equipment in a particular location through publicly available tools can play a role in proving war crimes later. Movements of transport aircraft from Ukraine (to Bulgaria, for example) can provide insights into armaments movements. These services can also be used to track the movements of planes and yachts owned by individuals with connections in the government.

Recently there have been reports that Google Maps has stopped hiding Russian military bases on the satellite imagery layer of its maps; this has not been confirmed, clear images of the bases have been available for some time, although the practice of blurring sensitive locations does exist. For example, last year researchers found that the clarity of satellite images of the Israeli-Palestinian territory on Google and Apple Maps is extremely low and has not been updated as often as other regions (so that, for example, some already destroyed buildings are still intact on the images), although high-resolution images are available from commercial companies.

Mobile non-military drones are another way to track troop movements and archive evidence. DJI drone distributors in Ukraine describe how, with the outbreak of the war, they discovered the potential of those devices to obtain real-time data on the conflict. There is a nuance: DJI devices are equipped with the Aeroscope system, which broadcasts the geolocation of not only the drone, but also its operator. The data is encrypted and can be obtained by special Aeroscope transmitters which DJI assures are sold only to the authorities and the police. On March 16, Ukraine's Minister of Digital Development tweeted a letter to DJI in which he claimed that Russian troops were using just such transmitters in the way they had used them in Syria - their coverage allegedly reached 50 km; he asked DJI to disable the Aeroscope functionality for Ukrainian drones. The company replied that the functionality was not switchable (although it had previously been added to older models of their drones via software updates) and that DJI was against using its devices in military operations. At the end of March the minister reported Ukraine had bought more than 2,000 quadcopters, including the DJI Mavic, and at the end of April the company suspended operations in Russia and Ukraine. There are already examples of drones controlled by civilians helping to obtain information about the location of Russian troops; there have been no instances of Aeroscope being used by the Russian side for aerial attacks on drone operators yet.

Ukrainians use a drone to record the location of Russian troops. AP footage

Finally, satellites help extract not only visuals information, but also audio data. For example, HawkEye 360 has satellites that can monitor radio frequencies, including military channels. The Russian military, due to problems with equipment and logistics, often uses unsecured communication channels. It was reported that the destruction of mobile towers made it impossible for them to use secure phones, which enabled Ukrainians to wiretap phone calls including those concerning Russian military casualties. The SBU also reported it had caught a hacker who routed calls and messages between members of the Russian military (including high-ranking officers) in Russia and Ukraine. The report was not independently confirmed, but if the published photos are to be believed, Russians used extremely unreliable equipment for this task - a SIM box with a GSM gateway, fairly easy to track. OSINT activists - ShadowBreak Intl., CIT, Bellingcat and others – report that for the first time in a modern military conflict, the Russian military is relying on civilian radios and mobile communications. This has already led to the creation of several large archives of Russian military conversations.

Big data analysis for proving complicity in war crimes

Videos recorded by the military have often served as evidence or proof of war crimes; it also happens because such material is sometimes used as propaganda, and the participants and sources are confident they will not be held accountable. For example, members of Libya's National Army posted videos of executions and torture of civilians on Facebook and Twitter to fuel violence. The Kadyrovites who are in Ukraine (probably assembled from the ranks of Rosgvardiya and the Interior Ministry and not involved in actual combat operations) have actively mediatized their presence by posting staged videos. But the rest of the Russian military has been consistently banned from using smartphones and social networks or from communicating with journalists for the past eight years by military unit specific decrees in 2014 and by a special law in 2019 and an additional decree in 2020.

Naturally, the Russian Ministry of Defense is not a source of reliable information about the conflict, but ordinary soldiers have also been deterred in their ability to intentionally or unintentionally record and leak any information (nor can they receive it: for example, in March it was forbidden to receive calls from Ukrainian and Belarusian numbers, and one of the conscripts from the Moskva cruiser who went «missing» called his mother on March 13 from a foreign number and reported their phones had been taken away and they had been banned from exchanging any information). On the other hand, the Ukrainian military and civilians within the conflict zone have been using all available means to record, archive, and stream everything that's been happening. In April, two private companies, AXON and Benish GPS, donated $4 million worth of equipment to the Ukrainian military to document Russian war crimes, including body cameras.

The Russian Ministry of Defense is not a source of reliable information, but ordinary soldiers have also been deterred in their ability to record and leak information

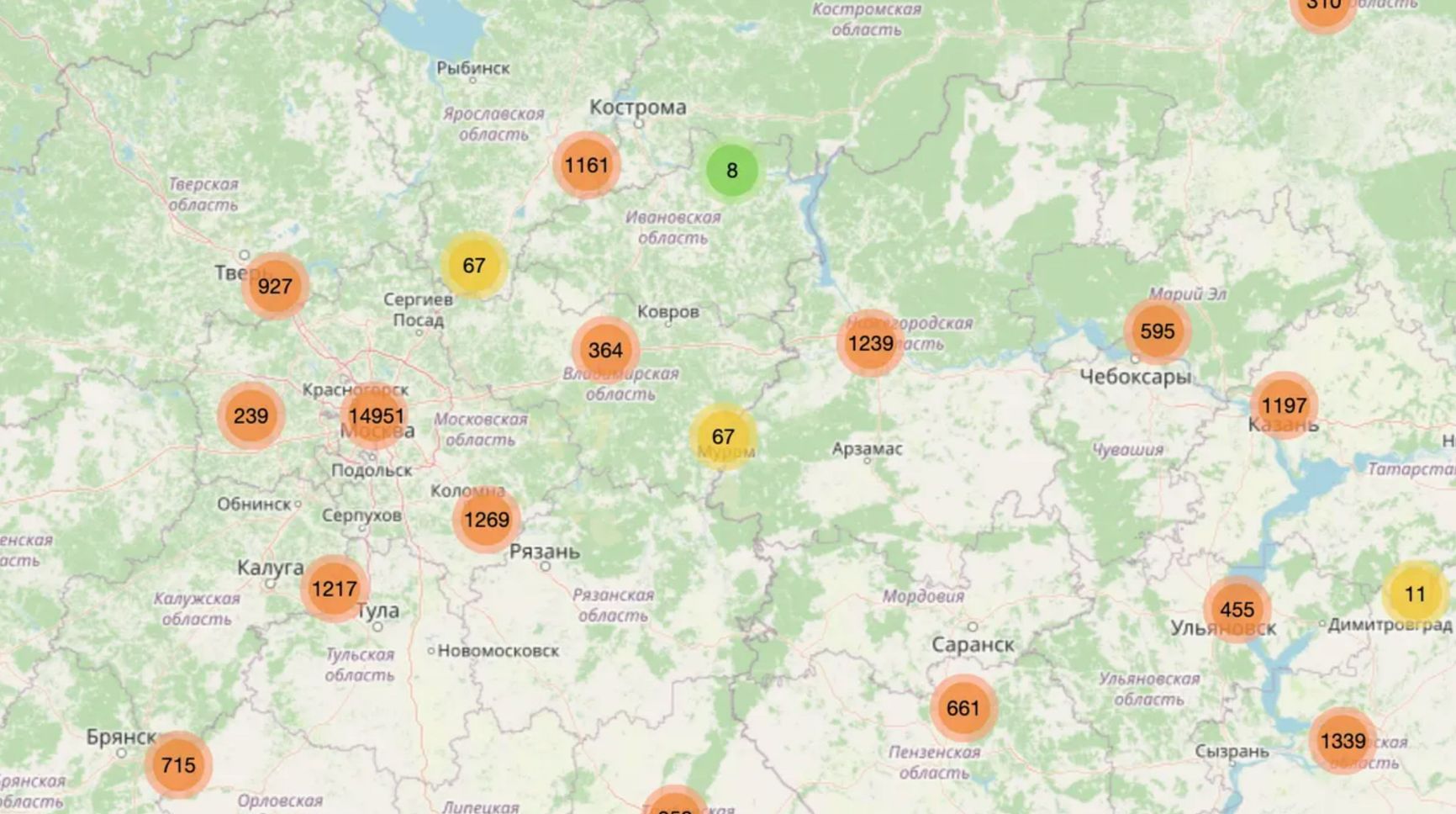

The huge amount of UGE (user-generated evidence) emerging from smartphones, handheld cameras, surveillance cameras, drones, wearable trackers, intercepted communications - posted on social media or sent directly to investigative, human rights or governmental organizations, has contributed to hybrid investigations like the piece in The New York Times on logistical and communication problems with the Russian army en route to Kyiv. The original facts came from a wiretap of unprotected conversations, but the audio could be falsified, so the NYT confirmed it in detail using geo-verified video footage, posts on officials' and propagandists' telegram channels, and photos of specific equipment. In the same video, the commands to open fire in a particular direction heard in the intercepted conversation are backed up by visual evidence of destruction. In other hybrid OSINT investigations, information is corroborated by mobile billing, satellite imagery, social media posts, information from leaked and purchased darknet databases, and hacked accounts. For example, at the end of March, a leaked database of Yandex.Food users revealed data on GRU employees.

Map showing leaked Yandex.Food data

One terrible example of necro-digitization at the beginning of the war was the Ukrainian Interior Ministry's Internet project «Look for Your Own.» Photos and videos of killed and captured Russian servicemen with their names, sometimes their cities of birth, and other personal data were posted there. In early April, Ukraine's IT Army's Telegram channel posted a «call to the Russians»: in the video, a narrator with a distorted voice demonstrated how facial recognition technology was used to identify killed Russian soldiers, find their social media accounts, and contact their relatives. Almost immediately, it turned out it was a development by Clearview AI, which, according to its founder, itself had offered and created more than 200 free accounts on its platform for five Ukrainian government agencies and translated the application into Ukrainian. Clearview AI has about 20 billion photos collected by scraping social media, including VKontakte and Odnoklassniki.

In the USA and some European countries there has been a public campaign against facial recognition technologies, and especially their use by the police, which has already led to a ban on the use of face recognition by law enforcement officers in some states and regions. High tech companies in various countries have been promoting FR as an important technology for «predictive law enforcement», but the entire history of facial recognition in cities is one of algorithmic errors and abuses. By the way, several soldiers sending parcels from Belarus with alleged Ukrainian loot were identified by Eric Toler of Bellingcat just by using the facial recognition service FindClone. The NYT quotes security researcher Peter Stinger as saying that the war in Ukraine is the first example of facial recognition being used on such a large scale.

The war in Ukraine is the first example of facial recognition being used on such a large scale

Facial recognition is powered by machine learning algorithms, part of what is now called «artificial intelligence» - and in recent years it has played a key role in the OSINT study of wars and conflicts. Even from regions not covered by technology like Syria, a huge amount of multimedia documentation is emerging. Before Ukraine, the war in Syria was the most documented conflict in history: by 2018, YouTube alone had collected more hours of video footage of the war than it actually lasted. No large investigative team, much less individual OSINT activists, could process such a vast amount of material. The question is how to process such a huge mass of information: to sift out duplicates and select really important pieces for manual processing; in the case of a war it is mostly about finding evidence of war crimes, extrajudicial executions, use of cluster weapons and other prohibited weapons. Deep learning tools that perform semantic segmentation of video and photo materials began to emerge during the Syrian civil war to solve these problems.

In 2019, Forensic Architecture, an investigative agency that uses architectural and digital techniques to investigate conflicts and crimes, released the Battle of Ilovaisk project which proved the presence of Russian troops in Ukraine in 2014. The project offered an interactive geo-temporal platform with hundreds of open-source testimonies proving the involvement of regular Russian troops and the presence more than 300 units of Russian military equipment on the battlefield. Forensic Architecture developed the Mtriage tool for that project, which automates media downloads from video hosting sites and social networks and analyses them by using pre-trained object detection classifiers.

Russian tank in Ilovaisk. Screenshot from the Battle of Ilovaisk project website

The project used so-called synthetic data, i.e. 3D-modeled images of objects used for training machine learning algorithms. Investigators needed to find a particular model of a Russian tank in the video material, but there were few images in the public domain to train the neural network, so the T-72B3 tank was drawn in a 3D editor and «photographed» in a digital environment from different angles, and from those screenshots a dataset was collected to train the ML-network. Evidence of the use of cluster bombs and chemical weapons during the war in Syria was collected in the same way. The Syrian Archive project developed by the human rights group Mnemonic archived more than 3.5 million videos. In order to find evidence of the use of the RBK-250 cluster bomb, they needed a neural network trained to look for such an object in the media; to train such the network, they needed thousands of different photos of the bomb. In collaboration with the Berlin artist and scientist Adam Harvey, 10,000 images of the RBC-250 were created and used to train the network that detected over 200 instances of the bomb or its fragments with 99% accuracy in an array of one hundred thousand videos.

Harvey posted his object detection model to the public domain, and recently a mechanism for detecting the letter Z, painted white on Russian military equipment and other items, was also made public. In turn, a collection of videos of detected cluster bomb explosions helped the investigators from Microsoft AI For Humanitarian Action to develop spectrograms of such explosions and use them to detect banned weapons from audio fragments. AI was also used in the Syrian war and other conflicts to analyze and translate documents, search them by keywords, transcribe and translate speech from videos, analyze sounds from audio recordings, find people in videos or photos, assess their age and even their mood. It can be done, for example, using the Zeteo software developed by the UNITAD investigation group or the open-source E-LAMP software from Carnegie Mellon University, which analyzes massive video arrays looking for objects, actions, written text, speech or specific human activities.

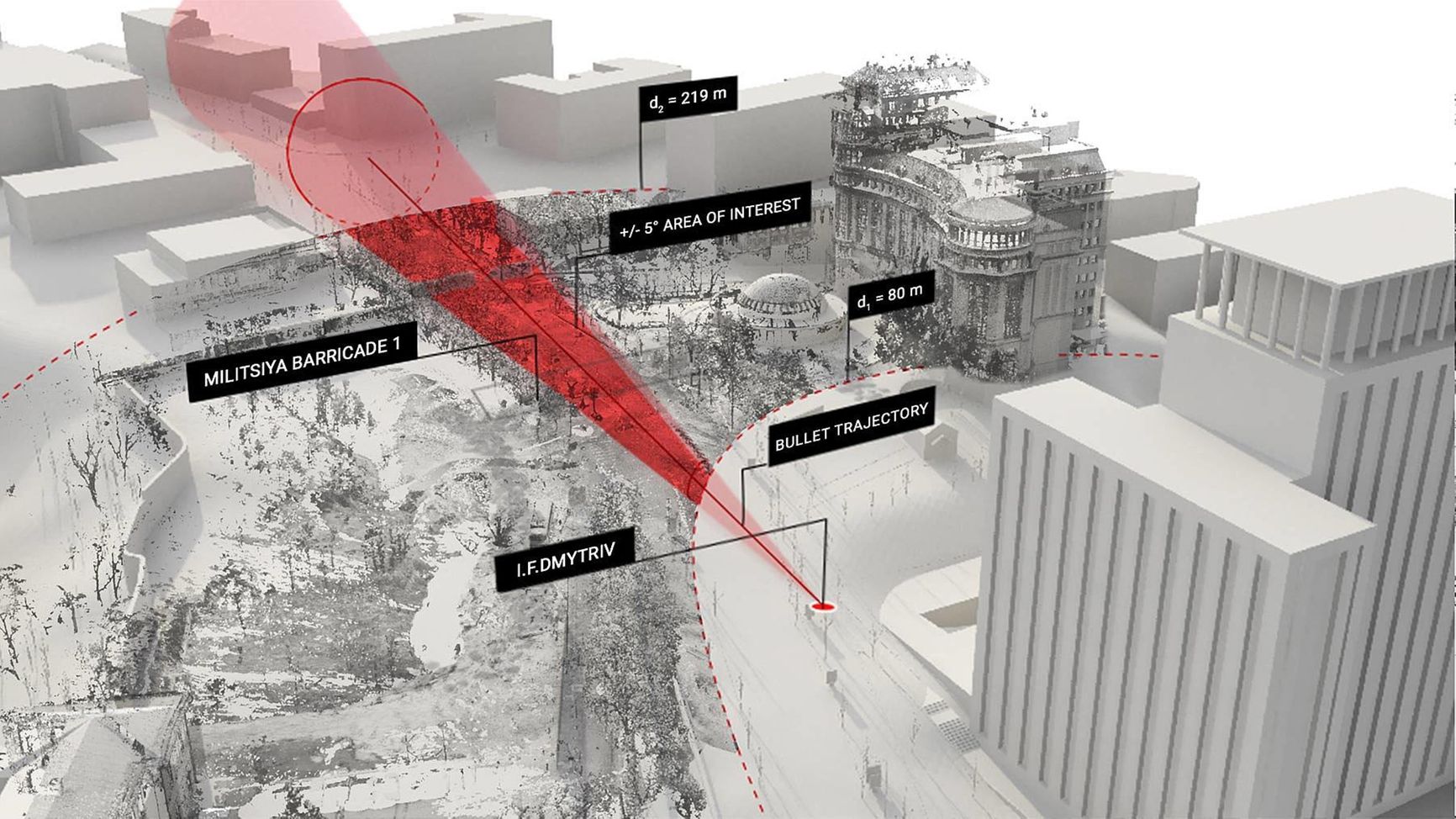

AI and computer vision were used by interdisciplinary research group SITU Research in a project to reconstruct the Maidan shootings in the winter of 2014, particularly on February 20, when 47 protesters were killed. SITU used ML algorithms to analyze and synchronize 65 hours of video. They also recreated Maidan Nezalezhnosti and nearby streets in 3D, including Institutska Street, and analyzed bullet trajectories, positions of victims and possible shooters, audio, and video recordings of the event.

Photogrammetry is also one of the most important tools for ascertaining the facts about war; it is frequently used by the Forensic Architecture group for investigating the Gaza conflict, the camps for political prisoners in Myanmar, the Beirut explosion, and other incidents. Together with Amnesty International, they reconstructed the architecture and the sound map of the place from the testimonies of former inmates of the Saydnaya military prison in Syria. Reconstruction of the crime space helps to either validate or invalidate the testimony of victims or perpetrators: in 2016, for example, Germany reconstructed the Auschwitz concentration camp and used VR helmets so that prosecutors in German courts, which were then hearing about 30 cases involving war crimes, could, for example, climb the guard tower and realize that the defendant was lying when he said he could not see people being taken to the gas chambers. It was recently reported that Ukrainian cities destroyed by Russian attacks will be digitized and made available in panoramas on Google maps; this will help assess the damage more accurately and will surely be an important resource for OSINT investigations and, possibly, lawsuits.

Reconstruction of the 2014 Maidan shootings. SITU Research website

In Russia's war against Ukraine, artificial intelligence is already being used to obtain and analyze evidence. Intercepted Russian military conversations are being recorded, transcribed, translated, and analyzed using the algorithms from the U.S. company Primer. Not only are Russia's military communications leaking in this war, but much more is going on: an unprecedented number of hacked databases and correspondence from government agencies and large companies have been made public in two months. The activist project DDoSecrets published around 3 million documents and emails in a month and a half of the war; some of the data turned out to be irrelevant, already seen before or partially relevant (like the mass doxing of 620 FSB employees) when looked at closely, but OSINT activists are already using AI algorithms to find important stuff among those documents.

Scale AI, a company specializing in deep learning, announced in early March that it would provide researchers, developers and Ukrainian government agencies with free datasets for the deep study of conflict-related data arrays. First and foremost, we are talking about the assessment of structural damage in Ukrainian cities as well as the analysis of satellite imagery for the detection and movement of military equipment. Berkeley AI Research has proposed a model for ML analysis of satellite imagery obtained through aperture-synthesis radar imaging - the one that is not hindered by clouds, smoke or changes in weather conditions; the authors say it can improve Ukrainian intelligence analytics.

Satellite imagery obtained through aperture-synthesis radar imaging. Screenshot from Berkeley AI Research website

It seems that the more data from inside the conflict zone, the better; but digital transparency creates vulnerability for all parties. The authors of an article in the International Review of the Red Cross on digital aspects of preventing and investigating conflict-related sexual violence introduce the concept of «digital body» as elements of women's (and not only women's ) physical bodies' presence in the digital space: their online profiles, photos, documentation of their abuse that can be shared by the military, and the data that women are required to share with human rights and humanitarian organizations to get help. They note that disregard for digital security is closely linked to possible risks to physical security in conflict, but they also write about possible predictive mechanisms to protect against sexual violence.

Digital transparency creates vulnerability for all parties

The aggression of Russian troops in Ukraine is the first case of mass rape that has drawn much attention, but nearly two decades of history of research into sexual violence in wars show that it is not random or sudden; it is often preceded by «rumormongering, hate speech, sudden or disorderly movement of troops, separation of men and women at checkpoints, and so on.» The patriarchal socialization of men in Russia and violence in the military and in the workplace make sexual aggression inevitable. Therefore, digital predictive technologies, such as tracking troop movements and moods based on AI analysis of satellite imagery and videos can reduce the risks of sexual violence during war - for example, by proposing timely evacuations. At the same time, ML algorithms are needed to analyze data on incidents of violence and collect digital traces left by suspected rapists.

In Egypt, activists created HarassMap, a platform that crowdsources data on sexual assault and violence, mapping them, informing about the overall picture of harassment and holding aggressors accountable. Another initiative, Callisto, helps victims of sexual assault get the help they need and add the incident and aggressor data to an encrypted database. Callisto has developed a matching mechanism that checks whether the aggressor has harassed anyone else, and if so, connects victims with each other and offers them further options in the legal field.

How to prove a war crime in The Hague

There is so much self-evident data coming out of the war that it seems as if justice - however brief, partial, whether in an international or local court - is inevitable. In reality, the International Criminal Court and ad hoc international tribunals have so far hardly used open-source media as evidence, relying mainly on witness testimony, documentary and physical evidence. Bill Wiley, director of the U.S. human rights NGO CIJA, who has been studying military conflicts for 25 years in terms of bringing the parties to justice, says that 99% of the footage currently filmed in Ukraine is useless for criminal proceedings.

The Bellingcat team, one of the most important actors in OS investigations, has automated scraping videos of explosions in Ukraine on major social networks. Another major NGO, Witness, trains civilians in Ukraine to shoot more valid videos – shake free, capturing essential details like weapons, equipment numbers, and faces of military servicemen. Human Rights Watch and the Amnesty International Evidence Lab collect video of attacks on civilian targets. London-based NGO Airwars monitors conflicts mostly involving air raids in Syria, Libya, Yemen, Somalia, and Iraq, estimates casualties, and archives data. After undergoing AI-based deduplication, analysis and sifting, the material will surely play a crucial role in independent investigations, but hardly in an international court of law.

The material will surely play a crucial role in independent investigations, but hardly in an international court of law

CODA quotes Dalila Muyagik from WITNESS as saying that the results of OSINT investigations «for the most part are not taken into consideration by courts, especially the International Criminal Court. For these kinds of courts, the most important thing is to prove the intention of the command to strike civilian targets specifically, with the understanding that there will be civilian casualties; the evidence of destruction does not suggest anything unless the intention of the particular persons who gave the order is proven, because the international court is focused on subjecting individuals to liability. However, it is possible to determine intent from open-source data; OSINT activists who have watched Russian troops in Syria see the same patterns of intentional destruction of civilian objects in Ukraine. «What happened in Aleppo in 2016 is happening in Mariupol and Kharkiv now,» says Syrian journalist Hadi al-Khatib.

Therefore, the question of documentation and archiving of what happened remains open. Many people remember their Instagram feeds and posts on the day when the photos from Bucha appeared: some media materials were hidden behind warnings and requests to confirm their age. Some were simply deleted by algorithms as being contrary to social media policies on depicting extreme violence, and corresponding tags were temporarily blocked. This is not a new problem, human rights and OSINT collectives had been encountering it as far back as the Syrian and other conflicts: YouTube, Facebook, Twitter and other platforms automatically or manually deleted what could have been evidence of war crimes. That is why WITNESS, Mnemonic and other NGOs have been trying for years to pressure the mega-platforms into creating special repositories for such materials, but no company has so far developed a clear policy regarding conflict-related content.

As soon as the war in Ukraine began, organizations like Bellingcat, TruthHounds, The Centre For Information Resilience, Reporters Without Borders started to collect deletion-proof archives. The Polish Pilecki Institute, which specializes in memory preservation, created the Raphael Lemkin Center for Documentation of Russian Crimes in Ukraine.

The use of the media and open-source data in criminal trials has been changing in recent years. In 2018, while trying two FDLR members accused of war crimes and crimes against humanity a Congolese military court for the first time used as evidence digital photos from the eyeWitness app, which stores metadata and sends it to a secure server, eliminating the possibility of manipulation (Hala Systems has a similar solution - they suggested sending metadata to the Ethereum blockchain, where data cannot technically be edited or deleted).

In the U.S., open-source evidence led to the launch of a trial against Sri Lanka's former defense minister on charges of assassinating journalists. At least six European jurisdictions are prosecuting cases against Syrian war criminals based on OSINT data, including the archive of 27,000 photos of murdered and tortured people taken or leaked from 2011 to 2013 by a war photographer under the pseudonym Caesar. OSINT investigations into the downing of Boeing MH17, which bolstered the JIT investigation, helped launch a trial against four suspects. At the International Criminal Court, the OSINT evidence served as the basis for the arrest of the Libyan National Army commander, confirmed the guilt of Ahmad al-Faqi al-Mahdi for the war crime in 2016, and helped open the trial against the four Cameroonian soldiers who had killed two women and two children.

In 2015, the International Criminal Court created a special E-court protocol defining the procedure for preparing and accepting digital evidence and testimonies. In 2020, the Berkeley Human Rights Center, together with the UN, released the Berkeley Protocol, a comprehensive international protocol defining the procedure for collecting and using open-source data in human rights advocacy and litigation.

The Ukrainian Legal Advisory Group, which has been collecting and analyzing war-related evidence together with OSINT activists, follows this protocol; ULAG director Nadia Volkova says the war in Ukraine will probably set a precedent for OSINT evidence to be considered in courts en masse. The courts' inevitable turn toward digital evidence is part of what researchers call the accountability turn, a third wave of institutional changes in international justice aimed at creating new mechanisms for prosecuting war criminals and collecting and analyzing data on particularly serious aggression against humanity.

The war in Ukraine will set a precedent for OSINT evidence to be considered in courts en masse

The Russian Federation, like Ukraine, is not a member of the International Criminal Court, having withdrawn in 2016 and never ratified the Rome Statute. This makes it impossible for the ICC to investigate Russia for the crime of aggression, which would have been the most effective case against Russian officials. And investigating war crimes and crimes against humanity sets a different bar of evidence, is more resource-intensive, and, as the ICC's 20-year history shows, very rarely reaches those responsible for the crimes simply because aggressor countries naturally do not extradite their own.

Nevertheless, the ICC investigation into Russia's actions was launched in early March, and as far back as 2020, a preliminary report by the ICC found «a reasonable basis to believe» that Russian troops had committed crimes against humanity in eastern Ukraine in 2014. Anyone who expects any kind of justice are now laying high hopes on the International Court of Justice. The same was true with the war in Syria, though, as that case shows, the hopes were largely in vain. In 2019, Professor Beth van Schaack released Imagining Justice For Syria, a book that exhaustively describes the international, national, and translocal justice mechanisms that may or may not be able to help the victims of this war get justice. She writes that much of the Syrian and international community looked to the ICC as a panacea and that it diverted attention and resources away from other, more expeditious justice mechanisms.

As strange as it may sound, there are processes more significant than trials of the guilty; the Nuremberg Tribunal did not prevent the emergence of dictators in the 21st century. Digitalization and crowdsourcing of data today allow us to learn and archive the truth about the war in a way that is different from what it used to be, on a civic rather than a state or institutional level. It is the way the memory of war has been preserved and glorified in the mainstream so far that makes the repetition of wars possible.