Russia ranks first in Europe for new HIV infections, according to recent UN data, with four out of every 10,000 people diagnosed with HIV infection annually. In 2021, 1.5 million new cases were recorded worldwide, of which 3.9% were in Russia, with a higher share only in Mozambique, Nigeria, and India. Over 1 million Russians are currently carrying the disease. This is the outcome of the failed policy pursued by the Russian government, which purchased useless tests instead of drugs, promoted conservative family values instead of safe sex, stigmatized same-sex intercourse, and banned substitution therapy instead of handing out syringes and condoms. Meanwhile, the organizations responsible for the “appropriate” propaganda continue to make good money.

Content

How Russia began its combat against AIDS

Artificial shortages of drugs

Testing instead of prevention and treatment

Celibacy and conservative values instead of sex education

«There is no such thing as safe sex.» Fidelity propaganda on the taxpayers' dime

Ministry of Health against condoms and for feel-good statistics

Murky social advertising contracts

The departure and second coming of Mazus

How Russia began its combat against AIDS

“Sensing some incomprehensible danger, one goes to Sokolinaya Gora today, to the address published by the media,” wrote the Ogonyok magazine in 1987. There, at Infectious Diseases Hospital No. 2, a community-funded office for anonymous HIV diagnostics opened after the USSR detected its HIV patient zero: a national of South Africa. Professor Vadim Pokrovsky received patients in a private consulting room. He sponsored the initiative to set up HIV diagnostics labs all over the country, and there were already about a hundred of them in late 1986. Dr. Pokrovsky referred to foreign students and people registered with drug abuse and venereal disease clinics as risk groups. “We expect active input from the police in identifying hotbeds of drug abuse, prostitution, and homosexualism,” the professor said at the time.

From the onset, Dr. Pokrovsky demanded that the government allocate money for prevention and treatment, warning that the lack of these measures would result in an epidemic in Russia – but up to this day, the Ministry of Health is yet to support his alarmist sentiments, although Russia's infection rate has long been close to that of Equatorial Africa.

With just a couple of rooms, Dr. Pokrovsky managed to scramble together enough equipment and reagents to diagnose HIV with high accuracy (by the then standards). The lab was manned by students, who worked voluntarily. One of them was Alexei Mazus, a first-year student at a dentistry college (Semashko Moscow Medical Institute). Years later, his official biography would suggest that he ostensibly founded this lab. Mazus later created the Anti-HIV Center for AIDS Prevention. It is hard to pinpoint the nature of the center's activities in the 1990s, as they received no media coverage except for occasional statements by Mazus, who criticized the existing laws for being too protective of HIV-positive people's rights. Mazus later re-registered SPID.Ru, the only Russian website on HIV and AIDS at the time (SPID is an acronym for AIDS in Russian), to his own company, and by the early 2000s, he had become friendly enough with the Moscow city administration to associate his center with a government organization. After that, Mazus launched an aggressive PR campaign, becoming a regular keynote speaker on HIV in the Russian media.

Artificial shortages of drugs

In 2000, Mazus reassured the nation: “Moscow passed the peak of the epidemic in 1999. <...> The epidemic is under the watchful eye of medics and scientists.” In reality, not only had the Russian public healthcare system failed to curb the epidemic, but it also had a poor understanding of how to combat it, opposing harm reduction programmes for injection drug addicts popular in the West. In 2002, the Wall Street Journal described the situation in Russia as follows:

“Many doctors who hold influential positions today were educated under the authoritarian Soviet public-health system. They disagree with Western methods of treating heroin addiction and controlling HIV, especially needle-exchange programs, which provide addicts with free clean syringes, and methadone therapy. Some doctors, such as Alexei Mazus, director of the Moscow AIDS Center and one of the most prominent AIDS physicians in Russia, oppose needle-exchange programs. They fear the practice lures youths into addiction.”

Meanwhile, independent HIV prevention projects for drug users were already operating in Moscow and St. Petersburg. Anastasia K., an HIV activist, recalls in a conversation with The Insider:

“In 1998, the Dutch branch of Doctors Without Borders launched a program in Moscow. Both staff and volunteers were drug users, most of them already living with HIV. Within a year, they had already started to publish the hottest magazine, Mozg (“Brain”), on all aspects of drug use. So two processes concurred in the streets of Moscow in the late 1990s: activists were raising awareness about harm reduction and the need to use clean needles, and the police were raiding pharmacies at night, rounding up those who came for clean syringes. At the same time, there was not enough antiviral therapy for all of Russia’s HIV patients, and it was rarely offered. It was a time rife with tension. To challenge the common prejudice that ‘junkies can’t take their meds on time’, protesters chained themselves to fences and took over the building of the Ministry of Health. The slogan ‘Living is our policy!’ appeared, as people were very afraid to die and demanded procurement of meds and access to generics. You could only get medication for a serious condition. That said, everyone knew there was treatment.”

Alexei Mazus, already the head of the Moscow AIDS Center, openly told foreign correspondents that they would not prescribe antiviral therapy to drug users, homeless people, and inmates, among whom the infection spread very quickly through injections of homemade drugs, because they would allegedly fail to adhere to their medication regimen.

However, the Ministry of Health preferred to procure the most expensive drugs, and none of them were manufactured domestically. In the early 2000s, the Ministry of Health turned a deaf ear to proposals by American foundations on setting up the supply of cheap generics to Russia to reduce the cost of treatment per patient.

In the early 2000s, the Ministry of Health turned a deaf ear to American proposals on setting up the supply of generics

Activists protested in multiple Russian cities, pointing to the near-total lack of relevant medicines in the country. The most vocal group was FrontAIDS: thus, in 2004, its members chained themselves to the doors of Kaliningrad city hall and also staged a rally with coffins in front of Smolny in St. Petersburg.

Testing instead of prevention and treatment

Russia's AIDS prevention campaign was centered on the promotion of testing, and its main ideologue was none other than Alexei Mazus. Test systems were purchased in huge quantities, not only for vulnerable groups but also for everyone else: primarily blood donors, pregnant women, and conscripts. Testing accounted for the most expenses of the government's anti-HIV/AIDS program – which, by the way, was underfunded by 50-95% in various regions. There was almost no money left for the modernization of hospitals, the creation of special departments, or even drug procurement. “Instead of improving hospitals, money was being wasted on completely ineffective mandatory testing and so on. Our healthcare system was not prepared for the epidemic,” a patient from Moscow's Anti-HIV targeted program explained to the BBC. In the meantime, the Mazus Center took pride in Russia having one of the highest HIV testing rates in the world: 15-16% in the mid-2000s.

Most of the funding allocated for the Anti-HIV/AIDS government program was spent on mass testing

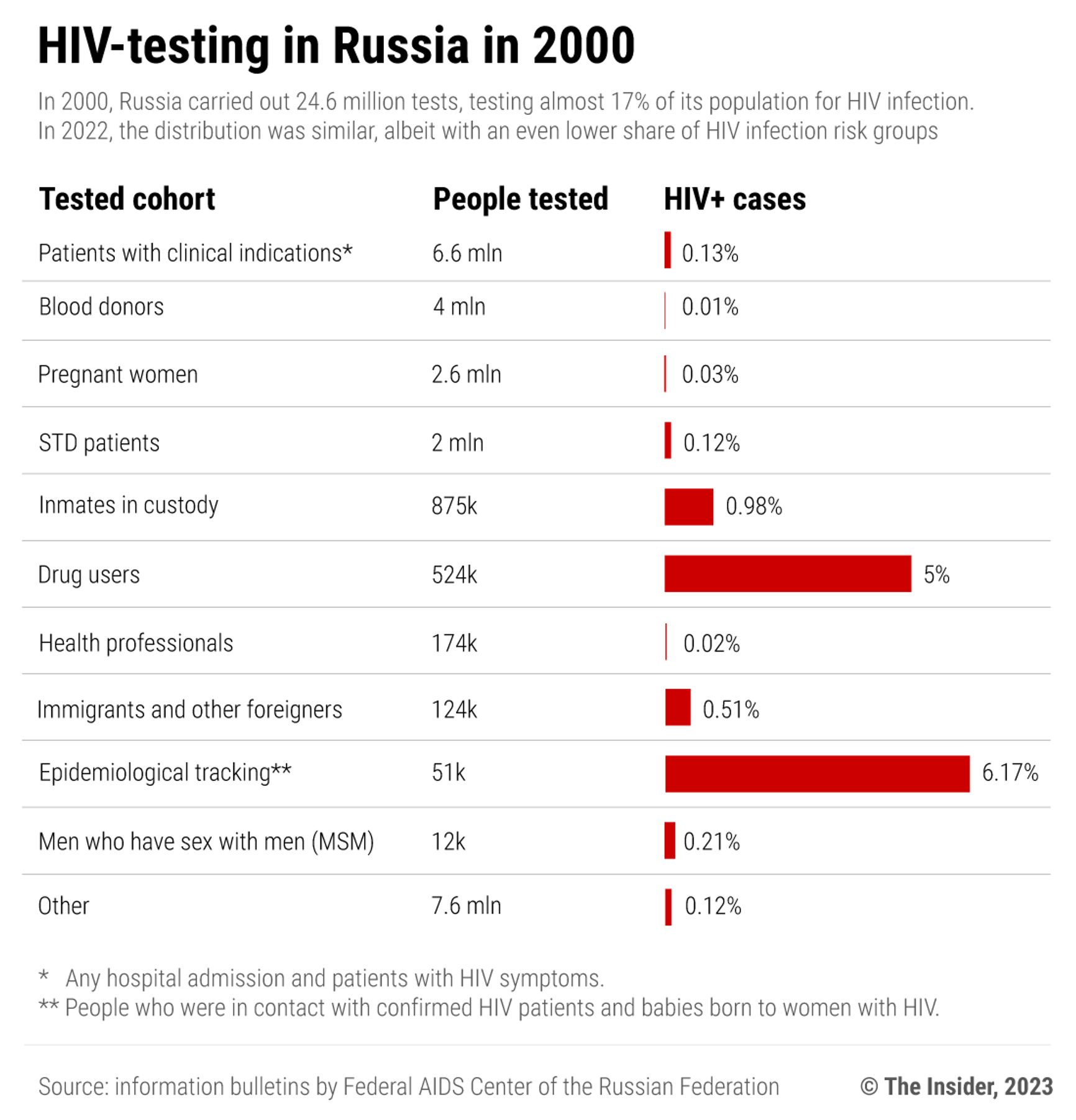

In 2000, Russia conducted 24.6 million HIV tests, covering nearly 17% of its population. However, according to the report of the Federal Scientific and Methodological Center for AIDS Prevention and Control, more than a quarter of those tested were pregnant women and blood donors; another quarter were tested for clinical indications (mainly those requiring tests for hospitalization), and 31% of the tests were for the “others” – without specification. However, the share of detected infections within these groups was minimal: 0.01-0.12%. At-risk groups – drug users, inmates, and men who have sex with men – were barely screened, accounting for under 7% of the tests.

Nevertheless, one in twenty drug users was found to be HIV-positive, according to The Insider's calculations. Supervisory authorities were aware of the fact that injection drug users accounted for the majority of infections (80-90%). Furthermore, about 1% of tested inmates were infected, which was far more than in other population groups (e.g., pregnant women or STD patients).

Over the last two decades, the situation with testing has changed little. All pregnant women, conscripts, and people admitted to hospitals still have to undergo mandatory HIV testing in Russia, even if they do not belong to risk groups, and even though cases of infection among them are extremely rare. Risk groups, on the other hand, are even less likely to be covered by the mass testing campaign.

This policy is rooted in the law on the prevention of the spread of HIV adopted back in the mid-1990s. The amendments to it, which provide for universal testing, were lobbied for by test kit manufacturers, as Dr. Pokrovsky explained to the Pravda newspaper:

“After the Duma passed the bill in the first reading <...> there was a struggle around it. In fact, the entire discussion revolved around just two articles of the bill concerning HIV antibody testing. The bill was attacked from two sides. The World Health Organization and various NGOs protecting sexual minorities criticized the bill for retaining provisions on the forced screening of certain groups and foreigners, seeing it as an attack on human rights. On the contrary, domestic test system manufacturers, who were after lucrative government contracts, and many physicians, who had little concern for human rights in a country that had abolished several constitutions and dispersed a few parliaments, demanded to expand the outreach of compulsory testing.”

A more humane bill, one that Dr. Pokrovsky's team had been working on since the early 1990s, never made it to the Duma. “We started writing an HIV bill in 1992, but it ended up burned in the White House during the shelling <in 1993 during the constitutional crisis – The Insider>,” he told Lenta.Ru. Dr. Pokrovsky declined to reveal to The Insider the names of the companies lobbying for mass HIV testing in the early 1990s.

As a result of the approach approved by the State Duma, almost all of the funds allocated for the federal Anti-AIDS program (1993 and 1996) were spent on diagnostic test systems. In 1995, Dr. Pokrovsky complained about the situation to Segodnya:

“What was the motivation behind this particular distribution of funds? The fact that practically no one controls the implementation of such programs. The Ministry of Finance allocates funds and the Ministry of Health and Medical Industry spends them as the administrators see fit, and their top priority is to support test system manufacturers, that is, domestic production. This is understandable because the industry employs about 10,000 people if we count both production and testing. Meanwhile, a lobby that would promote the considerations of prevention does not yet exist.”

One of the main test kit suppliers was ECOLab, a company founded in Elektrogorsk, near Moscow, by Seyfaddin Mardanly with the help of his acquaintances from the Ministry of Health. In the early 2000s, the market was redivided. This is how Seyfaddin Mardanly describes the times when Yuri Shevchenko became Minister of Health:

“A new team came to the Ministry of Health, took over the function of government contract distribution from the department of bacterial medicines, and set their own rules: cash kickback of 20% for distribution in someone's favor. They took everything from us in one fell swoop and gave it to others.”

In 2001, which is the period the ECOLab founder refers to, the Ministry of Health did adopt a list of recommended test systems, and priority was given to a US manufacturer, Bio-Rad. According to open-source bidding data and the State Procurement portal, for a long time, its Russian subsidiary, OOO Bio-Rad Laboratorii, was supplying the most test systems to Russian hospitals and institutions. For instance, it delivered $5.3 million worth of equipment to the Federal Medical-Biological Agency in 2008 and over $1.4 worth of equipment to Rospotrebnadzor (Russia's consumer rights regulator) in 2009-2010 (according to the public procurement portal).

Celibacy and conservative values instead of sex education

While supporting mass testing far beyond at-risk groups, the Mazus Center also opposed educational programs that non-profits attempted to implement with foreign grants. In 2005, Alexei Mazus co-authored a report under the auspices of the Moscow city administration, in which he criticized sex education in educational institutions:

“The barely-regulated teaching of 'safe sex' practices to Russian youth in such programs can serve as an example when a significant share of young people who are prone to risky sexual behavior were 'explained' that 'this little thing' in the form of a widely advertised condom is an indulgence for free sexual relations.”

At the time, the advertising of condoms as a means of disease prevention was sponsored by international foundations. For example, an advertising agency in St. Petersburg produced a series of videos and posters with the slogans “Choose Safe Sex” and “This Little Thing Will Protect Both” with funding from the international charity PSI Foundation. “Interestingly, since the launch of this program, infection rates among the younger group, 16- to 20-year-olds, dropped,” an HIV activist who wished to remain anonymous told The Insider. Meanwhile, Moscow authorities invested in commercials on the same channels and put up posters on the same walls with slogans like “A healthy family is your protection from AIDS” and “Safe sex is a myth”.

“It was in Moscow that bureaucrats hated the topic of ‘safe sex’ the most, and the city's Law No. 21 ‘On HIV’, dated May 26, 2010, imposed an explicit sanctimonious ban on condoms. Today 'physical contraception' cannot be promoted as HIV prevention at the expense of the budget,” notes Anastasia K. This was the first such regional law; previously, these matters were regulated by federal law. One of its authors was Lyudmila Stebenkova, a deputy of the Moscow City Duma, who was, like Mazus, opposed to condoms, homosexuals, and international NGOs, and advocated conservative “family values”.

At the federal level, the same policy was supported by Yevgeny Kozhokin, director of RISS (Russian Institute for Strategic Studies), the analytical center of the Russian Foreign Intelligence Service, who regularly co-authored reports with Mazus and published them on the Moscow portal SPID.Ru. Together, they promoted celibacy and fidelity as the pillars of HIV prevention. The authors made no secret of the fact that they’d borrowed the idea from the US government. There, however, it was repeatedly criticized by scholars and activists. In 2016, Stanford scientists debunked the approach as detrimental. They studied the conduct of people in subequatorial Africa, where the US sponsored a similar program, and found that social advertising for fidelity and celibacy did not lead to changes in people's sexual behavior. The authors emphasized that the money spent on promoting celibacy and fidelity could have been better used for other, more effective prevention measures.

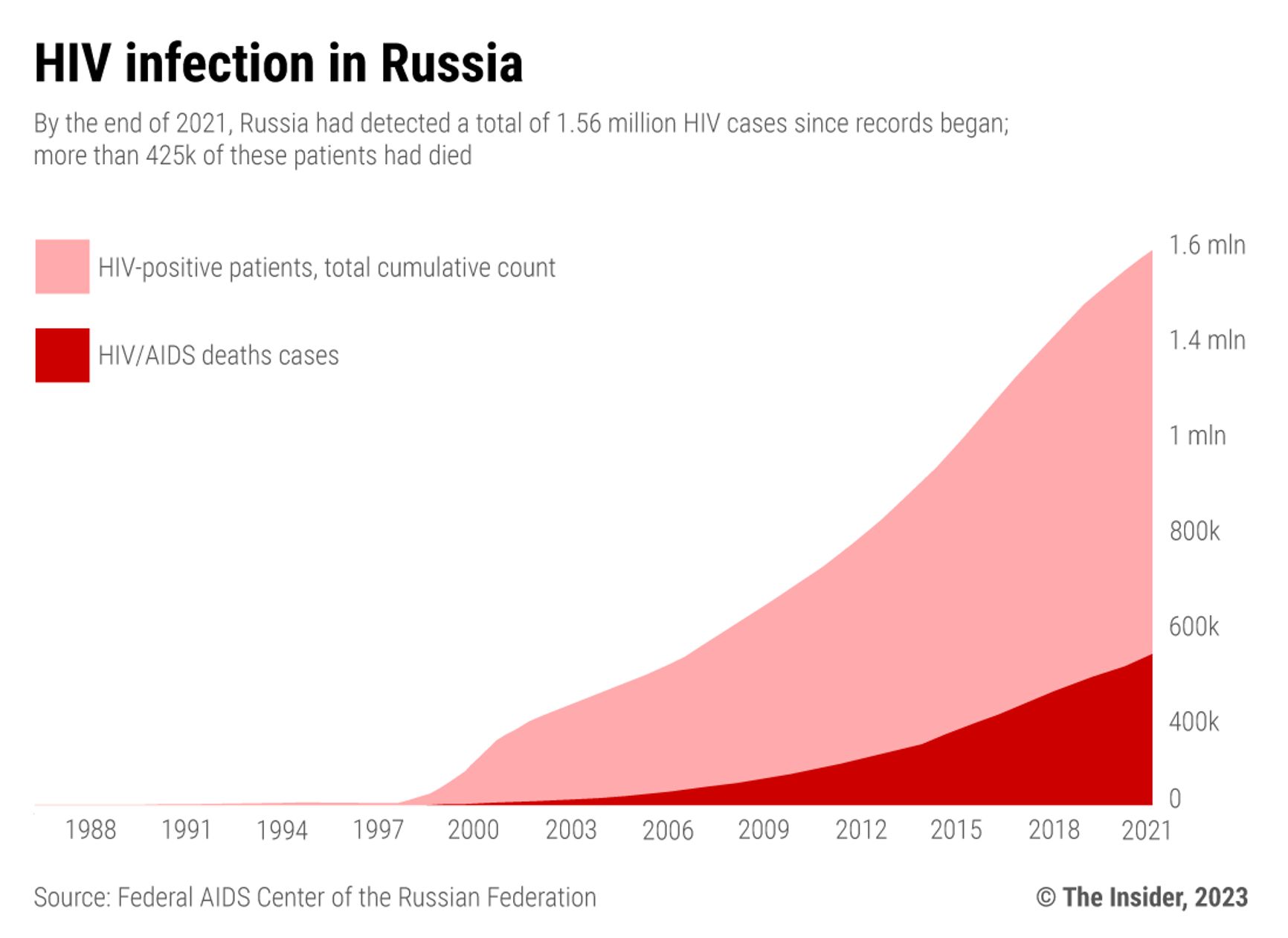

Apparently, promoting “good” family values has done little to help Russia. As of 2021, two-thirds of newly identified HIV patients assume they were infected during heterosexual contact. In the words of the federal AIDS Center, “HIV infection goes beyond the large reservoir” of drug users and homosexual men. At the end of 2020, seven out of every 200 men aged 40-44 in Russia were HIV-positive, and on average, up to 1.5% of adult Russians have HIV (in some regions and cities in the Urals and Siberia this figure exceeds 3%). To compare, in Southern African nations, this indicator exceeds 10%, and figures comparable with Russia are observed in Equatorial Africa: for example, in Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea. In the United States, this indicator is four times as low, and in Portugal, which faced a heroin epidemic in the 1970s and the 1980s, three times as low as in Russia.

According to Rospotrebnadzor, more than 1.5 million cases of HIV infection were detected in Russia from 1987 to 2021, and more than a quarter of these people have already died.

One of the main causes of Russia's situation is the large number of people who inject drugs, the United Nations Joint Program on HIV/AIDS says. Its guidelines state that Russia, combined with the US, China, and Pakistan, accounts for half the world’s injection drug users and that every four minutes one such person worldwide becomes infected with HIV. It is in harm reduction programs, such as the distribution of syringes and condoms, naltrexone treatment, and substitution therapy, that the UN program sees as the solution. China and the US are taking such measures, but the Russian government rejects such practices, prohibits substitution therapy, and brands NGOs working with vulnerable groups (such as the Andrei Rylkov Foundation, Humanitarian Action, Svecha Foundation, Fenix PLUS, and dozens of others) as “foreign agents”. The situation is similar in Pakistan, where the establishment opposes introducing drug substitution and harm reduction and criminalizes vulnerable groups (drug users and sex workers).

Alexei Mazus

The WHO cites sex education, condom use training, and sterile syringe programs as key measures to counter the spread of HIV, viral hepatitis, and sexually transmitted diseases. Testing, which Mazus prioritized, is also among key WHO-approved measures, but, unlike in Russia, the WHO suggests focusing on vulnerable groups. However, the international agency does not mention fidelity propaganda as an effective measure. The WHO also recommends that governments invest in combating stigma, gender-based violence, and the fight for gender equality.

In Russia, on the other hand, the opposite is true: same-sex relationships are stigmatized, and neither survivors nor law enforcement officials take sexual harassment seriously, according to a recent study by the Legal Initiative Project.

«There is no such thing as safe sex.» Fidelity propaganda on the taxpayers' dime

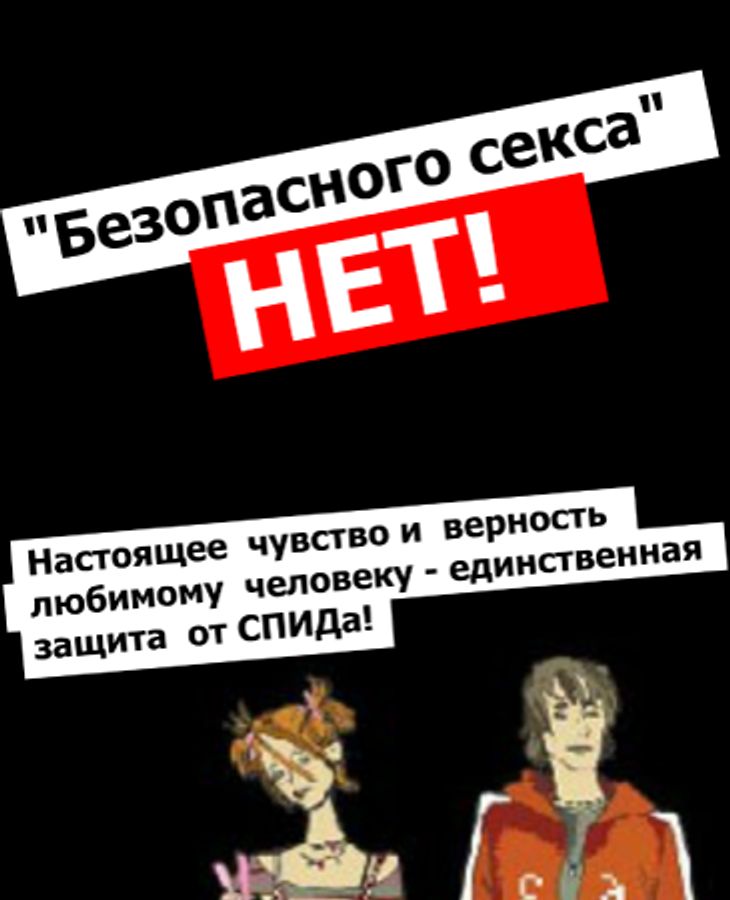

Having made universal HIV testing the state's main weapon against the epidemic, Alexei Mazus and his associates also decided to capitalize on social advertising against AIDS. OOO Anti-HIV-Press, a company founded with the help of Ilya Tsigelnitsky, began to receive government contracts for social advertising against AIDS. Alexandra Uskova headed the company; a few years later, she would take the last name Mazus. The company positioned itself as “the pioneer of domestic social advertising”, although such advertising had been on TV and in newspapers earlier. SPID.ru, a website belonging to Anti-HIV-Press, published videos and flash banners on the importance of staying faithful to one's partner to protect oneself against AIDS and the perils of drugs.

Flash banner on SPID.Ru, 2002: "There is no safe sex! True feelings and fidelity to your loved one is the only protection against AIDS!"

Wayback Machine

The website appeared to be associated with the Moscow city administration and Alexei Mazus personally. It published articles by Mazus with the same message: we need to test as many Russians as possible for HIV, and the only cure for the epidemic is a healthy lifestyle and lack of casual sex. The articles in which Mazus had a hand argued that condoms do not protect against HIV:

“I choose safe sex” is an advertising ploy invented by condom manufacturers to create the illusion of safe casual sex, which means selling more and more of their rubber products. ... There is no such thing as safe sex! Dear graduate, avoid casual sexual intercourse.”

The statement from the mayor's address has been refuted by scientists, such as American virologist Yegor Voronin, who has been researching HIV and the prospects of inventing a vaccine against it for over twenty years:

“No amount of scaremongering is going to keep teenagers from having sex. Emphasis should definitely be placed on condoms, which, when used correctly, are the best protection against HIV.»

You have to know how to use a condom correctly, too, and in some countries (e.g., Western Europe and African countries) this is taught at school in sex education classes. In Russia in the 1990s, sex education was introduced as a special lesson in biology classes, but today it is forbidden. According to a UNESCO metastudy, school curricula that promote sexual abstinence as the primary approach to combating HIV, other infections, and unintended pregnancy do not yield the desired results, whereas school curricula that focus on later initiation of sexual activity and teach the use of condoms and other contraceptives are the most effective.

The Mazus Center commissioned advertising from a subsidiary company not only for its website but also for television. By the mid-2000s, the commercials had become even more aggressive with loud slogans: “Vice propaganda reigns on the airwaves and in your head,” with a video sequence of half-naked girls and bugs crawling out of a young man's head. “No matter what your sophisticated friends tell you, casual sex is just a warped desire to exchange energy, to find the understanding, love, and warmth we all so desperately need,” with a video sequence of a palm speaking with a human mouth on it and more half-naked girls, dancing and luring men into bed.

Advertisements promoting fidelity in the first place were placed on Moscow's broadcast TV network and called for regular HIV tests at the same center on Sokolinaya Gora. In an interview with Moskovsky Komsomolets in 2003, Mazus boasted that Muscovites have access to the right information:

“We have a hotline and posters on the streets, but I have banned TV clips where a guy and a girl have just met and he's already giving her a condom: that's free love propaganda, not the fight against AIDS. Now they just tell you how to avoid infection.”

Lyudmila Stebenkova also promoted materials created by Anti-HIV-Press. It is hard to say how much such advertising cost Moscow and the Russian Ministry of Health because there was no open system of public tenders in those years. The Insider found data on several Moscow tenders for anti-HIV/AIDS education activities in 2005-2006, which showed that the Russian capital had allocated about $1 million a year for such measures.

The government budgeted a total of more than $7.5 million for such advertising and leaflets in 2002-2006, with most of it financed from the federal budget, while almost all of the burden of providing medication fell on regional budgets and was often underfunded.

The government wasted millions of dollars on fidelity propaganda, while the burden of providing medication fell on regional budgets

In a few years, the Mazus Center's subsidiary would be fully controlled by Alexandra Mazus. In 2020, the tax authorities declared Anti-HIV-Press an inactive company, and in 2022, Alexandra Mazus began the procedure of its dissolution.

Ministry of Health against condoms and for feel-good statistics

In 2010, Alexei Mazus became the Ministry of Health's chief external expert on HIV – a position introduced specifically for him. In his new capacity, he has tried to insert himself in the development of clinical HIV treatment guidelines, which outline the full scope of medical procedures for infected patients, from diagnosis to recommended drug regimens.

Mazus’ advent coincided with a scandal involving the Federal AIDS Center, headed to date by Professor Dr. Pokrovsky. By that time, the stances of Mazus and Pokrovsky, who had once started the fight against the spread of HIV in the Soviet Union and Russia side by side, had diverged greatly: while the first declared that the country had enough drugs for everyone and that the growth of infections was successfully curbed, the second insisted that the Ministry of Health underestimated the figures on the sick and the lack of drugs was catastrophic.

According to Vedomosti, the audit of Pokrovsky’s center in 2010 was conducted at the request of Lyudmila Stebenkova, a Moscow City Duma deputy and Mazus’ longtime associate, who wanted the disloyal academician to be put under scrutiny. There were even suggestions that Mazus should head the Federal AIDS Center controlled by Rospotrebnadzor, but this did not happen. This is how HIV activist Anastasia K. describes that time:

“When Vadim Pokrovsky remained in charge of the Federal AIDS Center after the inspections, everyone was even a little surprised. By then, he had cemented his reputation as a dissident, and there were two ‘HIV universes in Russia’: his and Mazus'. The Federal AIDS Center tries to keep statistics accurate and regularly issues newsletters that list the most affected regions, the increase in new cases, and even the increase in breastfeeding infections in the Caucasus. Mazus, on the other hand, has recently argued that there is no increase in new cases, but rather ‘test results recorded twice’. Pokrovsky writes about the shrinking outreach of testing among drug users and MSM, while Mazus reports the highest testing rates in the world. In interviews, Pokrovsky talks about condoms and substitution therapy, while Mazus likes to argue, in and out of place, that 'there is no such thing as safe sex'. How they get along in neighboring buildings is unclear.»

As the nation's chief HIV expert, Mazus continued to make reassuring statements that the spread of HIV in Russia had stabilized, appeasing the Ministry of Health and echoing the responsible ministry officials, who never missed an opportunity to point out that Russia’s HIV situation was better than in the US or Europe – in direct contradiction to the official statistics.

After the Ministry of Health appointed a chief external HIV expert, the Ministry's website began to publish articles stating that condoms do not protect against infection. The activists even launched an online petition against the display of these materials on the ministry's website. Vadim Pokrovsky also found them outrageous:

«Until recently, the Ministry of Health website featured materials about why you cannot rely on condoms. It took sharp criticism to clean it all up. As an alternative, some suggest staying faithful to your partner. The crusade for morality by Moscow City Duma deputy Lyudmila Stebenkova resulted in the disappearance of condom commercials on television, while the price for condoms rose to 600 rubles ($8) per dozen. Do you think many are willing to allocate that kind of money for this purpose? So we should at least think about how to stop the growth of prices for these products.»

Murky social advertising contracts

In the meantime, the government agency began to sign suspicious contracts for social advertising and surveys in this area. The terms of the contracts announced by the Ministry of Health suggested unrealistic timelines: the winners of the tender at the end of the year were supposed to spend a yearly anti-HIV propaganda budget in one or two months. In addition, when selecting the winner, preference was given to companies that bid higher than their competitors.

The Insider unearthed several such contracts from 2011-2012. For example, in October 2012, the Ministry signed a $6-million contract for television advertising for the rest of the year. In 2011, money was spent on the promotion of the Ministry of Health's new HIV website, which was abandoned after a few months and never updated again. The brochures printed as a result of the tender also did not reach their audience, as the contract failed to include logistics, and an additional agreement to this effect was never signed.

Back then, Alexei Navalny shed light on some of these contracts in his anti-corruption project Rospil – along with the human rights organization Agora, and the Public Chamber, after which the Prosecutor General's Office sent materials to investigators to open a criminal case.

The departure and second coming of Mazus

As the chief external HIV expert, Alexei Mazus co-founded a new organization in 2014 with a group of infectious disease doctors in Moscow – this time, a non-profit one: the National Virological Association (NVA). Its priority was to develop recommendations for HIV diagnosis and treatment. Although Russia's first official clinical guidelines for HIV treatment and diagnosis were published in 2013, the second edition came out as early as in 2014, under the NVA brand. Mazus headed the recommendation writing team for both editions. It is not known whether the association received money from the Ministry of Health for the effort.

Notably, these recommendations ignored the only domestic product at the time – the antiretroviral drug Phosphazide, which had already been on the list of vital and essential drugs (VED) for years, but suggested prioritizing Tenofovir, which was not included in the VED. Importantly, when a drug is not on the VED list, hospitals and the Ministry of Health are less likely to procure it, and the prices can be much higher. Phosphazide manufacturers faced pressure from competitors, said Dr. Pokrovsky.

In 2015, Yevgeny Voronin, an infectious disease doctor, replaced Mazus as the Ministry of Health's chief external HIV expert. Under his guidance, Russia adopted a 2020 anti-HIV government strategy, and the Ministry of Health began negotiating with suppliers to reduce prices (achieving a tenfold reduction in the cost of popular medication regimens in five years). Voronin also contributed to the development of new clinical guidelines. The Russian drug Phosphazide, which Mazus had ignored in his recommendations, was included in several first-choice regimens. Voronin also tried to get the modern drug Tenofovir included in the VED (Mazus had recommended it as a priority treatment), but the Ministry's commission refused to do so.

Suddenly, in mid-2020, the Ministry of Health announced that Voronin was no longer the ministry's chief external HIV expert and that Alexei Mazus was returning to the position. There was no special announcement of his reappointment; only a routine ministerial press release mentioning that Mazus now held the post again. This happened in the early stages of preparation of a new strategy against the spread of HIV infection for the period until 2030.

At the same time, Mazus’ National Virological Association became active. While her site had remained frozen after the 2014 recommendations came out, it was relaunched on a new domain. From the onset, the website featured the Association's version of the new clinical guidelines.

Moreover, the first thing Mazus did upon his reinstatement was to promote Elpida, a drug manufactured by his association's sponsor. Meanwhile, information about its interaction with dozens of other drugs was excluded from the recommendations, presenting it as a safer and preferable prescription option. However, Elpida was the most expensive HIV medication ($81 for a one-month course, which is 7% more expensive than one of the best drugs at the time, Tivicay). But its high price is not its biggest flaw. What's much worse is that it had barely been tested on humans, but the state is already spending millions of dollars annually on its purchases.

Read more about how Mazus made money on a drug with dubious efficacy in our story “The Mazus Case” (available in Russian).

The article was prepared with the use of Russian press archives. The full text of these items, along with the financial reports and constituent documents of organizations mentioned in the investigation are available on Github. The author extends their gratitude to the experts, who wished to remain anonymous, for their contribution to this story. The article is illustrated with images created with the help of the DALL·E 2 neural network. The collage features elements of video advertisements and posters by Moscow's Department of Health and Russian newspaper cutouts.