Russia has suddenly taken a harder line on stray animals. Some regions have already legalized the mandatory killing of stray animals, while others have been killing stray dogs and cats for decades — without any special legislation in place. The Insider visited dog shelters in the Republic of Sakha-Yakutia, where, according to volunteers and human rights activists, the cruelest methods of animal treatment are practiced. In 2020, over 200 dogs and cats were brutally killed at one of the shelters. Each animal had its throat slit. Just before last New Year's Eve, 500 animals at a shelter in Yakutsk disappeared without a trace. Volunteers are currently trying to evacuate the remaining animals to other regions, but the process is difficult and expensive.

Content

“Trappers are atrocious here”

Where did the 500 animals go?

The animal pound in Pokrovsk

Deadly surgery

“The euthanasia law will launch an endless conveyor belt of death”

“Trappers are atrocious here”

“I'll throw it out somewhere and let it die,” said the trapper, dragging a disabled dog by the leash to the gates of the shelter on Ochichenko Street in Yakutsk. The video of the shocked tame dog desperately trying to stand on its paws went viral on Yakutia’s social media in early January 2023. The trapping was ordered by the dog's owners, who decided to get rid of their aging pet. Employees from a subsidiary of the local utility services provider arrived and took the animal to the shelter. Once the trapper found out that the shelter could neither take on a handicapped dog nor euthanize it, he decided to drag it outside and “let it die.”

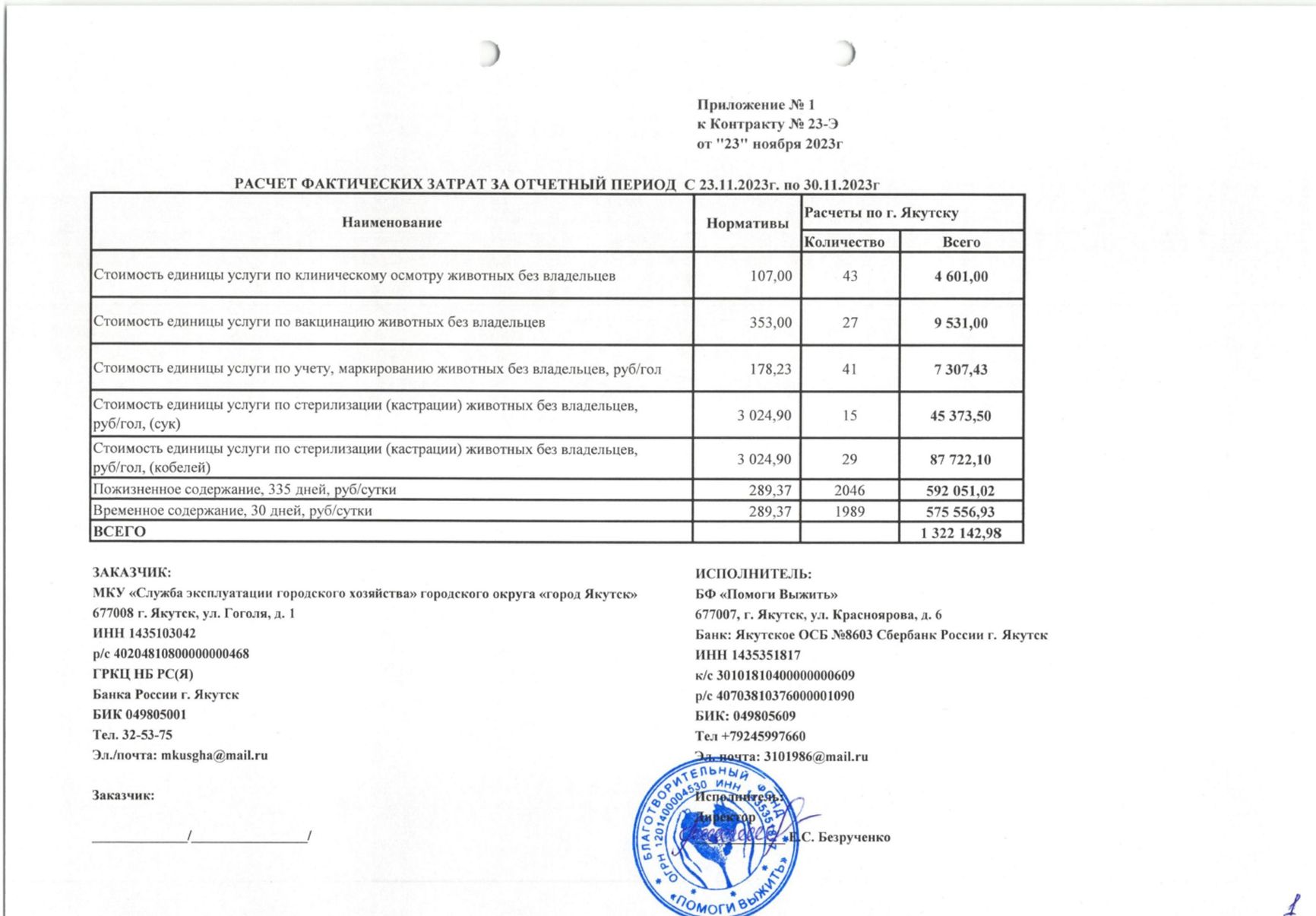

The lack of euthanasia services at the shelter raises questions. Contracts signed between the Yakutsk authorities and the managing organization of the shelter, a charity called Pomogi Vyzhit (“Help Survive”), include financing for euthanasia at a price of 162 rubles ($1.75) per animal. As the only bidder, the foundation wins all tenders related to stray animals in Yakutia.

The dog in the viral video was eventually rescued by the shelter director, who physically stood in the trapper’s way as he prepared to throw the disabled animal out. Volunteers found it a new home later that day, but the dog passed away one day later. “At least [it died] in a warm room and not in agony! Shame on the old owner, of course, for giving his friend to the animal abusers,” said Inna, a volunteer at the shelter. “Trappers are atrocious here. They catch dogs with wire loops and often bring them to holding facilities injured – with wounded ears or cuts on their necks.”

Frost-covered dogs in Yakutsk

The practices in Yakutia have shocked Russians attempting to solve their own stray animal problems in other regions of the country. Volunteers from the Schastlivy Bereg (“Happy Coast”) shelter in the Central Russian city of Lipetsk, who came to Yakutia to help catch stray animals, attest to the atrocities committed by local trappers. “They used slip nooses and ropes to catch dogs. It's an inhumane technique. We want to help remedy the situation,” volunteer Ivan Prokofiev said.

The crisis at the shelter was reported by several charities and volunteer associations:

“There is no kibble again. The dogs are fed once a day — sometimes even every other day, I suspect. The dogs are starving, turning on each other! No one is sounding the alarm. Why not? Probably because it would mean admitting their failure. The shelter's position, which is backed by reports from the supervisory authorities, is that everything is fine,” writes Marina Santayeva, a volunteer at the charity fund White Bim, named after a dog from a famous Soviet novel.

Inna complains that, “Everything about the animal holding facility is horrible. There is no quarantine zone for puppies. Weak animals are placed with strong ones, so they often don’t get any food. Aggressive ones destroy reasonable ones because the conditions are tough and no one monitors the dogs’ placement.”

The first thing that catches the eye in Yakutian shelters is the abundance of pedigree dogs: huskies of rare colors, malamutes, Siberian laikas, Akita Inus, Samoyeds, and more.“Such beautiful dogs and such a terrible fate! Even breed cannot save four-legged Yakutians,” Inna says.

Of course, not all of the unfortunate animals are prized breeds. “Not a looker, that one,” Inna says, pointing at a small dog curled up against the wall. She is the only one who does not react in any way to people approaching the enclosure, either too busy trying to keep warm or completely exhausted. Inna spent a long time deciding which dog to take in but eventually adopted all of them, including the small dog curled up by the wall. The next day, that dog gave birth to puppies. “I ended up saving 16 instead of 11 lives,” Inna says, spreading her hands.

The modest-looking dog who had puppies one day after being rescued from a shelter

But it is not always possible to rescue dogs from the shelter. On Feb. 16, volunteers tried to get two puppies out of a Yakut shelter, fearing they may not survive the cold weather. But the management only agreed to release one of them. “They refused to give us the other one. They said they had to keep him for at least 10 days. However, both puppies were admitted to the facility on Feb. 13. Why the selective approach?” White Bim volunteers complain. There is no telling if the tiny, short-haired puppy will survive 10 days in the Yakutian frosts.

The shelter gets 289.37 rubles ($3.13) per dog a day. But the funds aren't reaching the animals, according to association volunteers The Insider spoke to. Mass appeals to the prosecutor's office have been futile.

“The mayor, the prosecutor's office — all government agencies and supervisory bodies cover for each other,” Inna argued. “People barrage them with petitions, in writing and via the hotline. But all they get is formal notifications that their appeals have been referred to the Yakutsk prosecutor's office. To draw the attention of those in power, you have to go through the whole hierarchy — through every level. In all these years, no one has succeeded.”

The animal holding facility was founded in March 2015. At first, it was maintained by the municipal services provider ZhilKomServis. In 2021, it was handed over to the Help Survive Foundation and assigned the status of a shelter. The transfer occurred after the infamous “Yakutsk massacre” of March 2020, when a container with the bodies of more than 180 animals was found on the premises: the dogs had had their throats slit, and the cats had had their necks broken. The story made a splash — even the federal parliament called for an investigation into the “mass murder,” but no serious punishment was meted out to the management. The director of the facility was quick to state that the shelter had had to euthanize approximately 100 animals due to an alleged outbreak of rabies among the dogs. This explanation seems implausible: the dogs and the cats were being kept separately and could not have infected each other because the transmission of rabies requires direct contact with the saliva of an infected animal.

The volunteers are sure that the animals were slaughtered just to get rid of them.

“Euthanasia is expensive, but killing a weak animal by snapping its neck costs nothing,” volunteer Yana explains. “Or you could just release it into the wild at -45⁰C, where it will die. We have seen such cases too.”

Where did the 500 animals go?

On Jan. 3, volunteers from the White Bim Foundation brought hay for the dogs at the Yakutsk shelter on Ochichenko Street but were not allowed inside.

“We’re closed for disinfection for another three or four days. We'll be cleaning out the entire place,” the manager said.

She did not provide the exact dates of the disinfection — nor did she explain the need to clean the enclosures in minus-fifty-degree frosts. When the White Bim volunteers returned after the public holidays, they learned that at least 500 dogs had simply disappeared from the shelter. Their observation was confirmed by volunteers from other associations. They are trying to figure out what happened, but there is no definitive data.

“In a live broadcast on Dec. 5, Viktor Semyonov, the deputy head of Yakutia's Veterinary Department, stated that the shelter in Yakutsk had held 1,488 dogs. However, the figure mentioned at the city council meeting on Jan. 15, was 943 dogs. The difference is 545 animals! Where did so many dogs go? And why did their disappearance coincide with the so-called ‘disinfection’?” White Bim volunteers wonder.

A dog in an enclosure at the Help Survive Shelter

“When volunteers asked the mayor about the dogs' disappearance at a meeting with Promyshlenny District residents in January, he said they had been released into their ‘habitat’ — meaning they had been driven away from residential areas in severe frosts and left to die there,” Evgenia Makievskaya, a public inspector for animal treatment at national supervisory agency Rosprirodnadzor, tells The Insider. Dogs released outside the city stand no chance of survival — not only due to hunger and cold but primarily because of predators. Moreover, releasing dogs into the ‘habitat’ is in fact prohibited in Yakutia.

Dogs released outside the city limits stand no chance of survival due to predators

When the issue of the missing dogs was raised with shelter manager Rozalia Koshcheeva, she replied the animals had been taken in by volunteers. But placing so many animals at once is impossible. Only a few volunteer groups are involved in finding new homes for shelter dogs, and everyone contacted by The Insider confirmed that volunteers had not been allowed on the shelter grounds between Dec. 31 and Jan. 10.

Just before the animals’ disappearance in January, Yakutsk's municipal services provider SEGKh signed a government contract with the Help Survive Foundation worth approximately $64,800. According to the terms, the shelter is to provide a range of services for stray animals in Yakutsk, including vaccination, neutering, medical examination, euthanizing, and disposal of bodies. The contract is yet another in a series of agreements between SEGKh and the shelter going back years. The last contract before the mass disappearance of animals in January turned out to have been inexplicably expensive, totaling $59,400 for only five weeks: the last week of November and the whole of December. The preceding contract, which covered six months from February to August, cost only $32,400. Judging by the contract execution papers, not a single animal died at the shelter during its validity period, and no euthanasia was carried out. The shelter’s paperwork therefore provides no indication as to what happened to the missing animals.

Shelter record statements and actual expenditure reports do not mention killing or euthanizing animals or the disposal of bodies, which has led volunteers to believe that dogs are being “disposed of” illegally

“We don't know if the inflated contract amount is related to the disappearance of the dogs or not, but it looks suspicious. The problem is that we don't have supervisory bodies to check the activities of the shelter and its client enterprise,” a volunteer summarized.

The animal pound in Pokrovsk

Outside Yakutia's capital, the situation is even worse. Volunteers from the North Dogs Foundation have been visiting a dog shelter in the town of Pokrovsk, 80 kilometers from Yakutsk, for over a decade. By their estimates, the pound can hold approximately 50 dogs at a time. They live in bare wooden pens without even hay to keep them warm.

“The enclosures are littered with feces and look like no one ever cleans them,” a volunteer complains. “We were met by a tipsy guard who acted as though everything was in order. We've seen a lot of things, but we didn't expect to see something this awful.”

The animal pound in Pokrovsk in the summer

While the shelter in Yakutsk has at least a governance system in place, at the animal pound in Pokrovsk it is hard to figure out who is responsible for what, says volunteer Ekaterina. According to Russia’s Law on the Responsible Treatment of Animals, animal-keeping facilities require electricity and heating. Puppies and small dogs must be kept indoors. A shelter must also have access to veterinarian services. However, volunteers found no vet at the shelter in Pokrovsk. “No one is handling animal vaccination at the holding facility in Pokrovsk,” Ekaterina confirms. “There are no rooms allocated for the provision of medical services either. The facility only has one employee, who does not resemble a vet in the slightest, and he takes care of everything.”

The volunteers took three dogs with them: a half-dead male Laika, an emaciated female German shorthaired pointer, and a small mongrel puppy. All were taken to a veterinary clinic, but the Laika could not be saved and died on the same day.

A box of superglue at the Pokrovsk animal pound

At the clinic, the volunteers and doctors were in for another surprise: it turned out that the tags had been attached to the dogs' ears with superglue. Tagging animals is mandated by Russia's trap-neuter-release policy, with a budgeted cost of ear piercing of $1.93 per animal. Tags show that the dog is vaccinated and not aggressive.

“Back at the shelter, I wondered: why do they need so much superglue — an entire box? Here’s why! So where does the money allocated for the proper procedure go? Into someone's pocket,” Ekaterina suggests.

Deadly surgery

To control the stray population, the shelter in Yakutsk neuters animals. At $32.67 per procedure, neutering is the most expensive service in the contracts. However, surgeries are carried out in a mutilating manner, resulting in the animals dying, White Bim Foundation volunteers say. The foundation has two male dogs in their care that require treatment after undergoing the procedure.

At the shelter, the neutering is carried out by Ruslan Ivanov, a veterinary paramedic and close relative of Petr Petrov, the acting head of Yakutia's Veterinary Department.

“To castrate a male dog, Ivanov makes two incisions on the scrotum without subsequent suturing. As a result, the wound starts to fester, and the dog can die without treatment. In females, he ligates or removes one ovary but keeps the uterus. As a result, the dog can develop another lethal complication: pyometra, a purulent inflammation of the uterus,” reads the statement circulated by volunteers to raise awareness of the issue and encourage people to send petitions to the Ministry of Internal Affairs.

According to the volunteers, Ivanov also performs amputations on animals without following the rules of asepsis; in particular, he does not shave the hair in the area of surgery. This causes infection of the wound surface, necessitating a second surgery.

Volunteers posted videos of the complications of the castrations performed by him on social media. They presume that Ivanov is either not qualified to perform such surgeries or intentionally mutilates dogs to get rid of them. Volunteers are demanding that the prosecutor's office check the shelter for animal abuse.

“The euthanasia law will launch an endless conveyor belt of death”

The volunteers’ biggest fear is that Yakutia, along with Russia’s other regions, may pass a law ordering euthanasia for all unclaimed dogs after 30 days at a state-funded holding facility. All of The Insider's interviewees agree this will not solve the problem of stray animals. The number of strays on the streets will not decrease until the culture of pet-keeping changes. Therefore, great numbers of stray animals will continue to flow into shelters, and Yakutia will eventually set in motion an endless conveyor belt of death.

The main problem that makes it impossible to get the situation under control is the locals’ habit of releasing their dogs to roam freely. They often end up in the trappers’ hands and then in animal shelters. The republic fines the owners of unattended dogs, levying as much as $7,440 in 2023, but this restriction has done nothing to change the situation. Many owners also refuse to neuter their pets and, after they inevitably give birth, leave the unwanted offspring in boxes in the woods or in apartment building hallways. According to volunteer Inna, discounted neutering programs could increase the number of owners willing to bring their pets in for the procedure, but Yakutia has no such programs.

Together with Inna, we meet three dogs at Moscow’s Vnukovo Airport. According to the volunteers, evacuation is the dogs’ only chance of survival: “If you get the animal out of a holding facility, it won’t die, even if you haven't found an owner for it yet. That's a big deal! There are no healthy animals in those shelters. All are emaciated and have parasites, except maybe the ones that were in the shelter for a short time.” From the airport, the dogs will be taken straight to the veterinary clinic.

Crates with large dogs at Vnukovo Airport in Moscow

A trip from Yakutsk to Moscow costs approximately $300-400, but sometimes reaches $750, Inna says. First, the volunteers have to find a passenger willing to accompany a dog, then buy a ticket for the dog and register it in the passenger’s name. Tickets are usually scarce: one flight can carry two to four dogs. Large dogs are the most problematic. They rarely make it out of Yakutsk because it is expensive. People also tend to have the least compassion for them.

“Television makes them look like monsters, the incarnation of evil, blaming them for any episodes of aggression towards humans,” says Inna. “This kind of negative PR has irreparable consequences: brainwashed, cruel-hearted citizens go out into the street and fight the so-called ‘evil’ with their own hands.”

The problem cannot be solved by removing dogs from shelters because even if you evacuate all of them, there are dozens of new ones coming in every week. “We're not going to last long, either in terms of resources or psychologically. Where can we take all those dogs? Drop them off in Red Square?” Inna sighs. Luckily, the last batch of Yakutian evacuees have already found new owners in Moscow. In general, however, after the beginning of the full-scale war in Ukraine, fewer dogs have been taken in.

Runa, a dog rescued from Yakutsk, is being examined at a veterinary clinic in Moscow

“In a time of uncertainty and deteriorating living standards, the demand for Yakut dogs has somewhat slumped. Two years ago, it was easy to find a new home for our dogs in Moscow. It was enough to write an ad, and the dog soon went to the capital or its suburbs. It doesn't work like that anymore. Furthermore, the nation has been shaken by the situation in Buryatia, which passed a law authorizing the killing of its dogs, and people rushed to adopt Buryat animals. But our situation is no less dire.

“Discussions about the possibility of a euthanasia law have given the green light to animal abusers. They feel impunity because it is impossible to make them accountable for their actions — and the dogs die in agony, sometimes in front of children, while the police just laugh at us. Meanwhile, dog hunters gather in chat rooms and exchange recipes for poison and ways of ‘exterminating’ dogs,” says volunteer Irina, who sees the main problem in the general lawlessness. “As soon as there is punishment for throwing animals away and for their abuse, the situation will change for the better. The laws exist, but no one enforces them.”

All volunteers admit there have been cases of stray dogs attacking people. However, the media covers these isolated cases as though they were happening every day, Inna says. Russia’s problem of stray animal abuse could be solved by building warm shelters and developing a culture of humane animal treatment. Instead, stray dogs are being demonized, and cruel, inhumane initiatives resonate more and more with the general public.

“What we see is a culmination of anti-human initiatives!” the volunteer concludes.