A significant portion of Russian military recruits are men overwhelmed by microloan debt. They sign up for front line duty to settle their financial obligations. Meanwhile, The Insider has discovered that the main beneficiary of Russia's largest microfinance organization resides in Europe and oversees operations from abroad. The initial investment capital for the scheme likely came from his father, who is still wanted for his role in a high-profile real estate misappropriation involving a classmate of Vladimir Putin’s in — a case once dubbed by journalists as the “scam of the century.” Putin's ex-wife, who owns property in Spain, is also implicated in the microcredit business. As the Russian government sounds alarms over the growing consumer lending bubble, the microfinance organization co-owned by Lyudmila Putina-Ocheretnaya saw its profits surge by 66% in a year.

Content

Putin's classmate and the theft of cultural heritage

Microcredit bondage

Putin's classmate and the theft of cultural heritage

Many of Vladimir Putin's classmates have gone on to have remarkably successful careers. Alexander Bastrykin heads the Investigative Committee, while Irina Podnosova is the Chairman of the Supreme Court. Viktor Khmarin does not hold high positions himself, but his son leads the state company “RusHydro.” Businessmen Nikolai Egorov and Ilgam Ragimov have been richly rewarded for heling ensure the luxurious life of Putin's family.

Another classmate of Putin’s, Anatoly Shesteryuk, also received an influential position but lost it due to a corruption scandal. Shesteryuk, who graduated from Leningrad University in 1975 alongside the future president, now leads a more modest life as a professor at the Department of Environmental and Land Law at Moscow State University.

Shesteryuk resides in the White Swan residential complex near his workplace. His 204-square-meter apartment there is valued at around 150 million rubles ($1.7 million), and he spends much of his free time at a suburban dacha in the Novaya Opaliha gated community. Once, as the head of the Territorial Department of Rosimushchestvo in Moscow, Shesteryuk was in charge of all the capital's real estate and had access to properties designated as historical monuments of architecture.

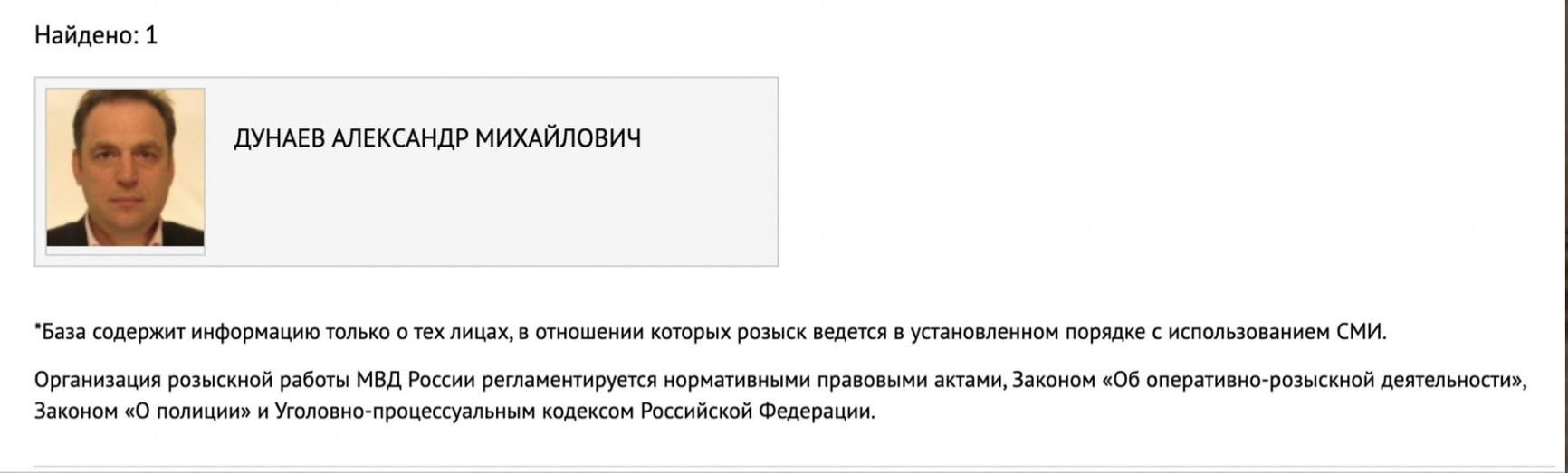

When Putin was elected for his third presidential term in 2012, Shesteryuk almost ended up in prison. He was detained by operatives from the Main Directorate for Economic Security and Anti-Corruption of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Russia and the Anti-Corruption Directorate “K” of the FSB's Economic Security Service. Charged with fraud, he was initially held in a pre-trial detention center but was later released on his own recognizance.

In time, the criminal case against Shesteryuk, dubbed the “scam of the century” by the press, gradually lost momentum and eventually fizzled out, but at one point it appeared to have the potential to become one of the most high-profile cases in recent Russian history.

In brief, the scheme involving state property theft revolved around Shesteryuk transferring state-owned buildings in Moscow to specific Federal State Unitary Enterprises controlled by a criminal group. These enterprises acted as guarantors for fictitious loans that various LLCs took out from a bank that was in cahoots with the fraudsters. The real estate was then sold off to private buyers at bargain prices.

As a result, more than 100 properties were at risk of being sold off, many of which were listed as federal cultural objects, according to Kommersant. Among them were 28 architectural monuments in central Moscow, including the 19th-century Rogozhskaya Yamskaya Sloboda ensemble, the Dolgorukov house from the mid-18th century, and the Snegirev estate from the early 19th century. Additionally, the Federal State Unitary Enterprises owned assets such as a printing complex from 1936 and the Church of the Holy Supreme Apostles Peter and Paul in Yasenevo.

Several historical mansions were stolen by Putin's classmate and his accomplices, with investigators estimating the state's losses at over 2 billion rubles ($23 million). However, Shesteryuk escaped accountability; instead of being accused, Putin's classmate was positioned as a witness. He claimed he had been misled by his own assistant and was merely “honestly mistaken,” effectively shifting blame onto minor and inconsequential figures.

Supposedly, the mastermind behind the entire scheme was businessman Alexander Dunaev, who fled from the investigation and remains a fugitive.

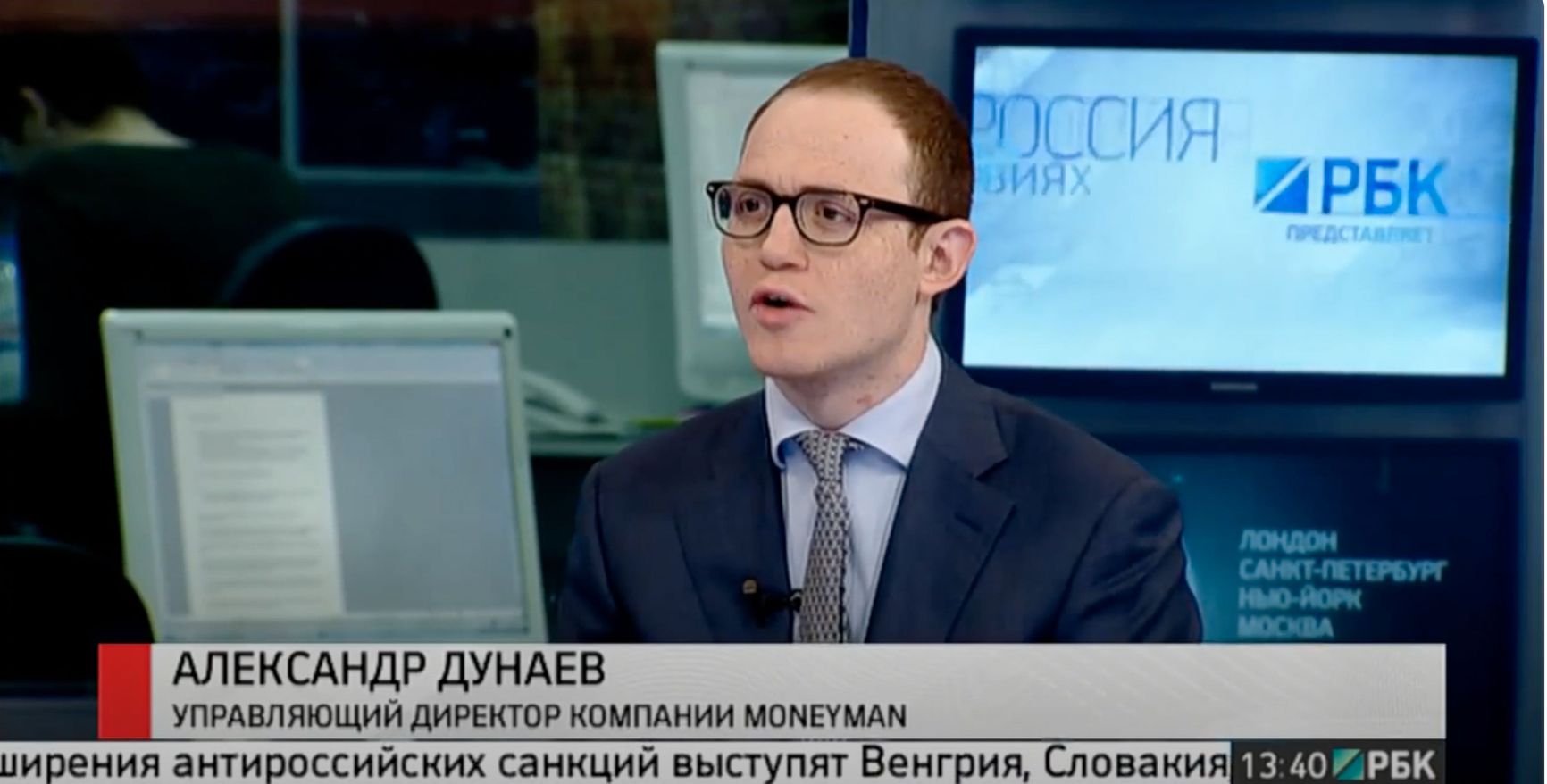

Dunaev has a son, also named Alexander, who was educated in the UK at the University of Warwick and King's College London. In 2012, amidst the unfolding scandal surrounding the “scam of the century” orchestrated by his father, Dunaev Jr. founded Russia's first online microfinance organization, MoneyMan. MoneyMan, part of the larger IDF Eurasia group of brands offering Russians “financial technologies in the field of lending,” ranks among the leaders of the country’s microloan industry.

Microcredit bondage

In addition to MoneyMan, the IDF Eurasia group also owns the online loan platform Platiza, along with its own debt collection agency. Dunaev holds the largest stake in the group. By the end of 2023, MoneyMan had issued nearly 46 billion rubles in loans, marking an 18% increase from the previous year. The IDF group reported a net profit exceeding 4 billion rubles ($45.4 million). While formally legal, this business exploits the financial distress of millions of Russians by offering loans at excessively high interest rates, ultimately pushing them toward financial ruin.

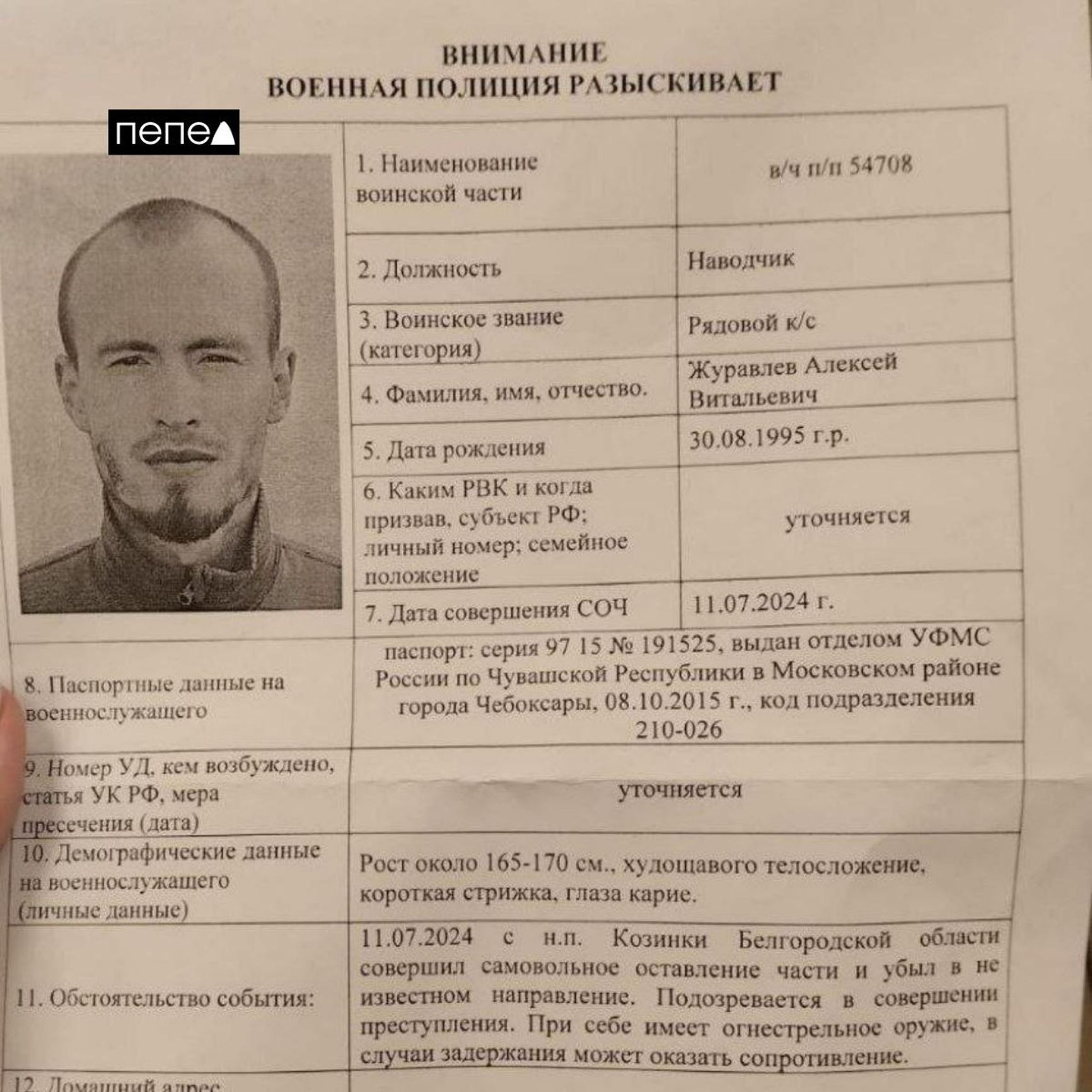

The widespread entrapment of Russians in microloan debt has made recruitment efforts by the country’s Ministry of Defense significantly easier. Many men, like 28-year-old Alexey Zhuravlev from Chuvashia, sign up to repay their debts. Zhuravlev, who previously worked in construction and accumulated debts totaling 260,000 rubles ($2.950), was unable to secure new microloans. Consequently, he enlisted in the military for service in Russia’s “Special Military Operation.” During a drunken altercation with fellow soldiers, Zhuravlev fired a machine gun, resulting in casualties.

Authorities are actively encouraging debtors to enlist in the military, with bailiffs almost acting as recruiters. Earlier this month, a Tatarstan news site told the story of a local man who successfully discharged microloan debts of nearly half a million rubles ($5,700) by signing up with the Ministry of Defense. However, not everyone is as fortunate, and many Russian soldiers sent to the front lines in Ukraine carry their debts to their graves.

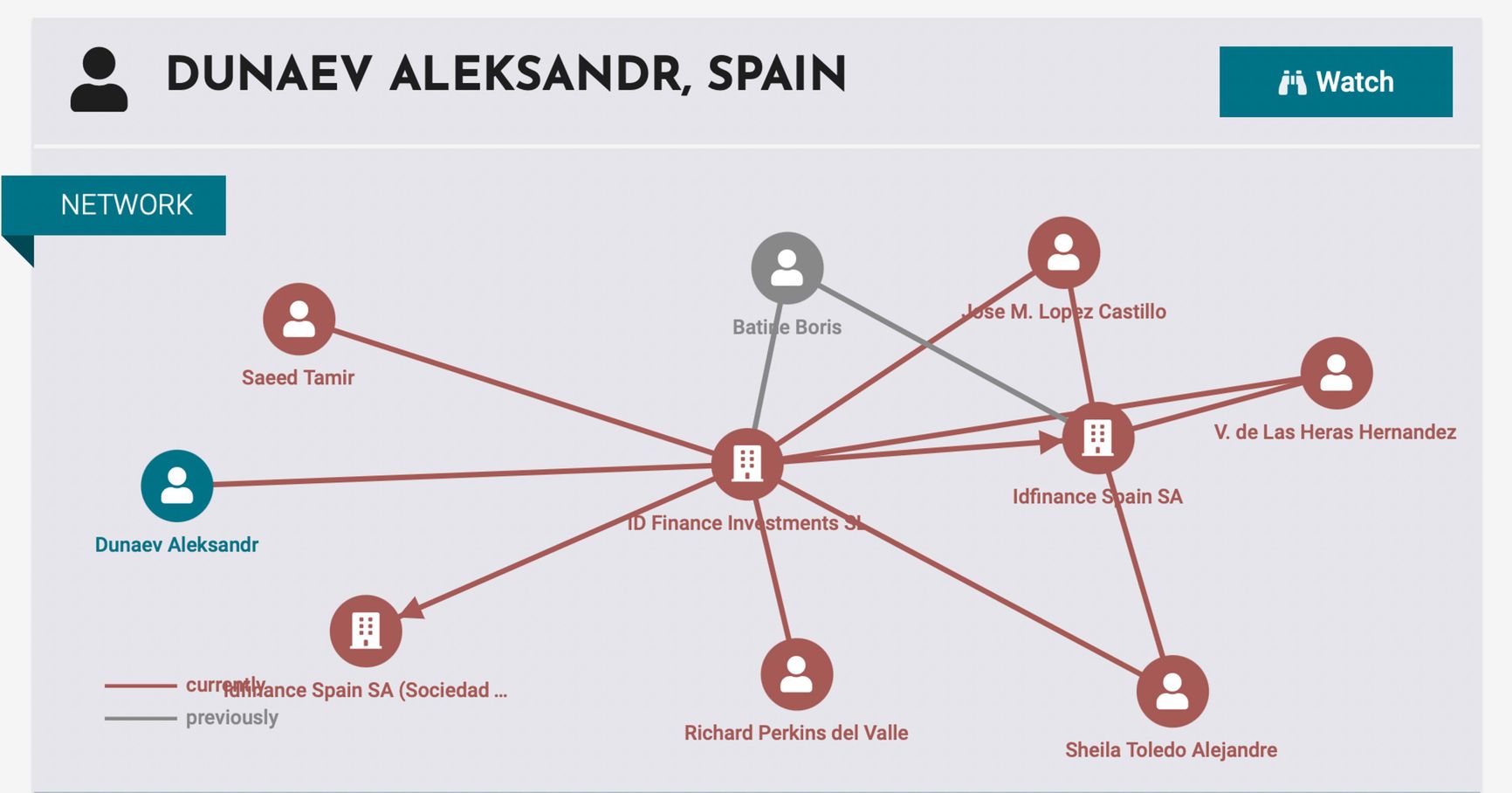

Meanwhile, the main beneficiary of Russia's largest microfinance organization resides in Europe: Alexander Dunaev owns upscale real estate in Barcelona. According to information from the Spanish real estate registry obtained by The Insider, Dunaev and his wife possess a 161-square-meter apartment and a 536-square-meter villa purchased last year. The combined value of their properties in Barcelona totals approximately 4 million euros.

Furthermore, Dunaev oversees his microfinance operations from Spain. Several of his companies, including ID Finance Investments, are registered there.

Another Spanish real estate enthusiast — Putin's ex-wife Lyudmila Ocheretnaya — also profits from the microfinance industry. The earnings of CarMoney, a company in which Ocheretnaya holds shares, surged by 66% over the past year. Ocheretnaya also owns two luxury apartments in Malaga.

While ordinary Russians’ debts to microfinance operations reach record highs, all but ensuring that the pipeline of “volunteer” soldiers keeps pace with Russia’s staggering losses on the battlefield, the well-connected beneficiaries of these enterprises continue to enjoy the sunny climate — and the institutional rule of law — in Western countries like Spain. Meanwhile, the Russian government appears to have no intention of regulating the practices of microfinance organizations that exacerbate Russians’ economic vulnerabilities, even as their beneficiaries continue to spend their profits in the supposedly decadent West.