Russia attacked Kharkiv in the first days of the full-scale invasion and even managed to occupy large parts of the surrounding region for several months. The city, with a population of over one million, remains on the front lines, suffering daily missile and drone strikes. Arriving in his hometown, journalist and Armed Forces of Ukraine serviceman Yuriy Matsarsky saw that despite the Russian strikes, not only does life in Kharkiv continue — cafes, the subway, and even the zoo are open — the mood in the city is more patriotic than ever. Kharkiv residents are increasingly switching to Ukrainian for daily communication, and they continue to do all they can to support the AFU. On the streets, the city’s monuments have even undergone an unmistakable makeover.

Content

“Fog” instead of Patriots

“I spoke this language for 50 years, but seeing what the Russians have done to our Kharkiv, I dream of forgetting it”

“LGBT people are patriots, like other Ukrainians”

Monuments of (imperialist) culture

Other signs of war

“Fog” instead of Patriots

The Epicenter hypermarket in Kharkiv, which was destroyed by a Russian missile in May 2024, still smells of cinders. The empty parking lot outside sports a giant graffiti message, so large that viewers must walk from one English language letter to another to make out the words: “God saves our souls, Patriot saves our lives.” The graffiti also includes a schematic, childlike drawing of the Patriot, an air defense system capable of intercepting Russian ballistic missiles of the sort that have been raining down on Kharkiv.

Ukraine received about a dozen of these systems, but they never reached Kharkiv. The command has decided against bringing Patriots to the city, fearing for their safety, as Epicenter is barely 40 kilometers away from the Russian border. A Russian missile covers that distance in less than a second, and if one of the Russian reconnaissance drones constantly circling over the city spotted a Patriot, it would be almost impossible to protect the launcher from Iskander missiles. As a result, instead of modern air defense systems, Kharkiv has to make do with outdated Soviet surface-to-air missile systems, mobile units in pickup trucks with machine guns that intercept suicide drones, and the Tuman (“Fog”) GPS jamming system.

If a Russian reconnaissance drone detected a Patriot, it would be almost impossible to protect the launcher from Iskander missiles

Tuman is activated every time a radar detects Russian aircraft capable of carrying guided bombs, which happens at least ten times a day. Tuman jams GPS signals, sending any Russian bombs off target while at the same time causing taxi drivers' navigators to go haywire and city visitors to get lost on their way to the destination.

However, the “fog” is useless against missiles, and the charred ruins of the Epicenter clearly prove this fact. The facade of the hypermarket, although badly damaged, has yet to collapse, and the store sign, which now has Ukrainian flags hanging from it, survived. But the insides of the hypermarket are a chaos of charred metal structures, collapsed roof sheets, and heaps of goods smashed and scattered by the shockwave. Occasional price tags, faded under the merciless summer sun, are a surprising sight.

At the entrance to the ruin, Kharkiv residents have set up an impromptu memorial: photos of customers and staff killed in the attack pinned to a lamppost, candles, and a heap of stuffed animals. Sometimes gusts of wind scatter the toys around the parking lot, but the security guard, a stout man in his 60s, always picks them up and takes them back to the memorial. It's not the store he is guarding — there is nothing left to steal anyway, as everything was destroyed either in the explosion or in the fire that followed. His job is to keep away gawkers.

“You can take any pictures you like, just don't go beyond the tape — it's dangerous there,” the guard points to the white-and-red plastic ribbon lining the facade. “Something might fall on your head.”

Like many Kharkiv residents of his generation, the guard speaks Russian. But teenagers and young adults are increasingly using Ukrainian. In the 1980s, the opposite was true: while the older generation was Ukrainian-speaking, younger people spoke almost exclusively Russian.

“I spoke this language for 50 years, but seeing what the Russians have done to our Kharkiv, I dream of forgetting it”

Overall, Kharkiv’s Russian-language space is noticeably shrinking. A few years ago, most advertising signs were in Russian, and even after the Russians seized Crimea and started the war in Donbas, stops in the subway were announced in two languages: Ukrainian and Russian. Today, Kharkiv's subway is at the forefront of de-Russification. This year alone, three stations changed their names in order to rid themselves of any Soviet or imperial associations: Heroiv Pratsi (‘Heroes of Labor) became Saltivska, Pushkinska became Yaroslava Mudroho, and Pivdennyi Vokzal (‘South Station’) became Vokzalna — because Kharkiv's central railway station could be considered a gateway to the south only for the Russian empire; for independent Ukraine, the city lies in the north of the country.

Street advertising is also being Ukrainianized. Some old signs have already been replaced with new ones in the official language. Others have been corrected with a felt-tip pen or paint — since both languages use the Cyrillic alphabet, minor adjustments were sometimes enough.

One of the few remaining signs in Russian

“I spoke this language for 50 years, but seeing what the Russians have done to our Kharkiv, I dream of forgetting it,” Olena, a cashier in a small grocery store just off the city's main Sumska Street, says in not-so-smooth Ukrainian. “There’s not a spot left in the city that hasn’t been bombed.”

Utility workers pile up the debris of structures hit by missiles or suicide drones every day to be trucked to a landfill

In Kharkiv, one can see marks left by Russian strikes at every step: craters from mortar shells on the pavement, historic buildings destroyed by missiles, walls peppered by shrapnel. Utility workers pile up the debris of structures hit by a missile or suicide drone every day so that the detritus can be trucked to a landfill. If you see such a pile in the street, you understand that a tragedy occurred in this neighborhood only a few short hours ago: someone may have been killed, injured, or lost their home.

A pile of debris on the pavement means a tragedy occurred just a few hours ago: someone was killed, injured, or lost their home

“LGBT people are patriots, like other Ukrainians”

Russian bombs and missiles are hitting museums, libraries, and Christian Churches — including those of the Moscow Patriarchate.

The partially destroyed dome of a Russian Orthodox Church belonging to the Moscow Patriarchate

One of the attacks damaged the already dilapidated building of the Kharkiv kenassa — the place of worship of local Karaite Jews. It may have been the same missile that left Kharkiv Pride, an LGBTQ+ rights group, without its headquarters, as the shelling of the Podil neighborhood in central Kharkiv damaged the sewage system, flooding the basement where Kharkiv Pride was based.

The activists spent a long time looking for a replacement for their old headquarters, receiving neither hindrance nor help from the city authorities. Eventually they purchased a spacious semi-basement in the historical center of the city, where they held another parade in early September. Local far-right activists tried to disrupt the rally but failed — largely thanks to the strong police presence in the street where the new headquarters is located.

One of the main complaints voiced by the ultra-right against the LGBTQ+ community is the alleged non-participation of queer people in the war against Russia. Some even accuse sexual minorities of aiding and abetting the occupiers. However, Kharkiv Pride activists insist this is a myth of homophobic propaganda.

“LGBTQ+ people, just like the rest of Ukrainians, went to volunteer in the first days of the war. They are just as likely to be drafted into the army as anyone else. Those of us who are not in the army donate money, volunteer, buy cars and drones, and weave camouflage nets. We love Ukraine. We are patriots,” explains Maria (name changed), a Kharkiv Pride activist, in fluent Ukrainian.

Maria’s speech is interrupted by the siren: another military aircraft has taken off in Russia’s Belgorod region, meaning that guided bombs will soon be falling on Kharkiv or its suburbs.

“Let's move to the back room, away from the entrance and windows,” orders a girl with a short haircut wearing a traditional vyshyvanka shirt with rainbow-colored embroidery. “Safety first.”

Pride participants drop everything they are doing — trading souvenirs, drawing funny faces on the wall, discussing news, taking pictures in a corner labeled “Marriage Zone,” weaving camouflage netting — and rush to the back room. Only a couple dozen attendees of a tactical medicine master class remain in place. The young tattooed teacher, seemingly unperturbed by the howling of the siren, continues to talk about the differences between venous and arterial bleeding and demonstrates on herself where to fix the tourniquets in order to stop the hypothetical gushing of blood.

The alert lasts only a few minutes. The occupiers must have dropped the bombs on the areas of Kharkiv Region that are closer to the border with Russia. But Kharkiv itself gets a bit of a beating that day, too. Russian bombs later fall on several parts of the city, collapsing walls and blowing out windows in multiple buildings. At this point, one would hardly find even a single building in Kharkiv with all of its windows intact.

One would hardly find even a single building in Kharkiv with all of its windows intact

It's probably easier to find a dozen houses that don't have any windows left at all. Both in the center and in residential areas, entire blocks have plywood in window frames — and on what used to be glazed facades. Some of these panels are decorated with patriotic designs, but most are plain sheets used instead of glass where windows were blown out by blast waves or shrapnel.

"Amulets of our time"

Despite the never-ending attacks, Kharkiv's restaurants, cafes, shopping centers, and markets continue to welcome customers. Even the zoo is still open, and entrance is free. Neither the numerous visitors nor the zoo animals react in any way to the constant howling of sirens — or to the distant explosions.

Kharkiv zoo

Monuments of (imperialist) culture

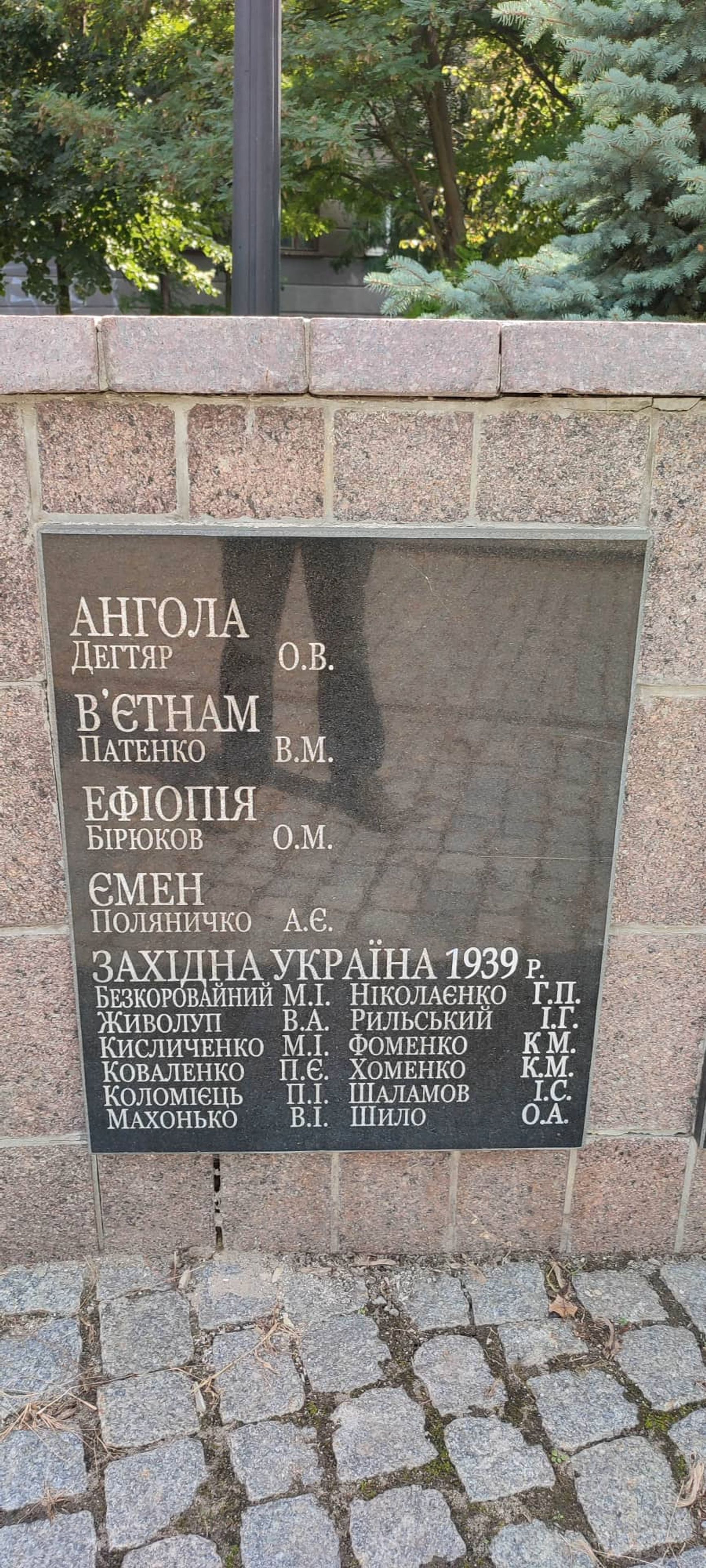

Within a fifteen-minute walk from the zoo lies one of Kharkiv's most controversial memorials — a monument to local “internationalist” soldiers who died in the countless wars fought by the Soviet Union far from its borders. Until a year ago, in addition to the usual mention of those fallen in Afghanistan, Angola, and Mozambique, the monument featured a plaque with the names of Red Army soldiers — natives of Kharkiv — who died in 1939 in western Ukraine. In other words, they were fighting in the army that started World War II in alliance with the Nazis, raising arms against their compatriots: Ukrainians from Lviv and Ternopil.

"Angola. Vietnam. Ethiopia. Yemen. Western Ukraine, 1939." The photo was taken in August 2022. The plaque has since been removed

That plaque is gone now, dismantled without much publicity — just as the bust of Russian poet Alexander Pushkin had been dismantled shortly before. Nevertheless, Kharkiv still has quite a few controversial monuments, and no one is in a rush to demolish them. For one, the monument to the mythical (if not to say “fairy-tale”) city founder, Cossack Kharko, by Moscow-based sculptor Zurab Tsereteli, which once outraged patriotic Kharkiv residents, still stands, protected from Russian strikes with sandbags and boards just as meticulously as Kharkiv’s signature monument to Taras Shevchenko on Sumska Street.

The monument to the mythical founder of the city, Cossack Kharko, by Zurab Tsereteli, is protected from Russian missiles with sandbags and boards no worse than the monument to Taras Shevchenko is

A year ago, a British WWI-era Mark V tank also stood covered with sandbags next to an unprotected Soviet T-34 on the square in front of the historical museum. Now the bags are gone on the Brit as well.

The British WWI-era Mark V tank in front of the historical museum

However, the most noticeable metamorphosis happened to the Walk of Fame of the Kharkiv Lilacs Film Festival (2009-2013). Each celebrated actor or director participating in the festival was commemorated by a metal plate featuring a cast of their hand, along with their name and surname. These plates were displayed on special stands along a walkway in the central city park.

Among the famous participants were Russians who subsequently endorsed Russia’s occupation of Crimea, its seizure of Donetsk and Luhansk, and its full-scale invasion of Ukraine; some of them even illegally visited Russian-occupied Ukrainian territories. The plates with their names were not taken down, but instead covered with thick white cloth.

Letters on some of the plates still show through the tightly fitted fabric, and with a little effort, one can discern the identities of the undesirable figures. Among them is the composer Maxim Dunayevsky, a fan of vacations in occupied Crimea. Another plate was dedicated to actor Alexei Petrenko, a native of the Chernihiv Region and a graduate of the Kharkiv Theater Institute — from 2014 until his death in Moscow in 2017, he never made any public statements about his attitude to the war unleashed by Russia against his country of origin.

Near Kharkiv University, the inscriptions on the monument to 19th-century scientist Vasily Karazin, its founder, are also covered with thick fabric. The two hidden plaques on the opposite sides of the pedestal featured Karazin’s quotes, in which he glorifies Russia and emphasizes the need to work for its benefit.

These words are not just inappropriate, but truly blasphemous in the modern context, in which the university is facing the building of the Kharkiv regional administration, where 44 people were killed by a Russian missile attack on Mar. 1, 2022. Behind the partially destroyed administration building, one can see a few more severely damaged apartment blocks and business centers, including an old residential building that used to host the famous Old Hem Pub in its basement. Neither the pub, nor the monument to Ernest Hemingway outside, nor the portraits of writers — including Soviet dissident author Sergei Dovlatov, that once hung on the walls — survived. A missile fell on the building roof, tore through all of the floors, and exploded in the basement. Through the hole it made in the facade, one can see the insides of the apartments. There is still some furniture and even plates with exotic landscapes on the walls, once brought home by the owners of the destroyed apartments from a vacation.

Other signs of war

Ruins, never-ending strikes, and shrouded monuments are not the only signs of war that catch the eye in Kharkiv. There are strikingly few people in the streets. The subway no longer has rush hours, even though all of Kharkiv's public transport has been made free during wartime. The intervals between trains are unusually long: 10 minutes on workdays and 20 minutes on weekends.

Schools and universities are empty. However, classes continue, either remotely on Zoom or in underground facilities set up by the Mayor's Office. Traffic jams are rare and only occur in the event of massive road accidents. Unfortunately, the latter have become frequent, as many roads remain blocked with concrete slabs that are barely visible in the dark. The city still maintains the mandatory blackout mode at night. Even central streets and squares are not illuminated, and inexperienced drivers or those unfamiliar with the route often run into obstacles, blocking entire lanes.

Inexperienced drivers or those unfamiliar with the route often run into obstacles, blocking entire lanes

And yet, notwithstanding the ongoing attacks, the destruction, the permanent mortal danger, and the significant outflow of citizens, Kharkiv is holding on. While Russian propagandists called it a “Russian city” for many years, Kharkiv is demonstrating an indomitable desire to never actually become one. Despite the danger of Russian attack, the one evening the city permitted itself to light up the night came on City Day, Aug. 23, which happens to be the eve of Ukrainian Independence Day.

Nothing in Kharkiv has been left untouched by Russia’s war, and as a result, even its outskirts are more Ukrainian than ever. The never-ending fences of the city’s industrial zones, through which the train slowly crawls toward Poltava, were once covered with graffiti bearing the logos of soccer teams and popular music bands. Now these walls are almost entirely covered with emblems of army brigades, portraits of fallen defenders of Ukraine, and panoramas of the Kremlin in flames. When the train stops to let a freight heading toward Kramatorsk and Kostiantynivka pass, one can discern a short inscription made on a trackside pole in the neat handwriting of a schoolgirl: “Russians, you’re f*cked.” These are the last words we read on the way out of Kharkiv.